Voriconazole is a safe and effective anti-fungal prophylactic agent during induction therapy of acute myeloid leukemia

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2016; 37(01): 53-58

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/0971-5851.177032

Abstract

Background: Antifungal prophylaxis (AFP) reduces the incidence of invasive fungal infections (IFIs) during induction therapy of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Posaconazole is considered the standard of care. Voriconazole, a generic cheaper alternative is a newer generation azole with broad anti-fungal activity. There is limited data on the use of voriconazole as a prophylactic drug. Materials and Methods: A single-center, prospective study was performed during which patients with AML undergoing induction chemotherapy received voriconazole as AFP (April 2012 to February 2014). Outcomes were compared with historical patients who received fluconazole as AFP (January 2011-March 2012, n = 66). Results: Seventy-five patients with AML (median age: 17 years [range: 1-75]; male:female 1.6:1) received voriconazole as AFP. The incidence of proven/probable/possible (ppp) IFI was 6.6% (5/75). Voriconazole and fluconazole cohorts were well-matched with respect to baseline characteristics. Voriconazole (when compared to fluconazole) reduced the incidence of pppIFI (5/75, 6.6% vs. 19/66, 29%; P < 0.001), need to start therapeutic (empiric + pppIFI) antifungals (26/75, 34% vs. 51/66, 48%; P < 0.001) and delayed the start of therapeutic antifungals in those who needed it (day 16 vs. day 10; P < 0.001). Mortality due to IFI was also reduced with the use of voriconazole (1/75, 1.3% vs. 6/66, 9%; P = 0.0507), but this was not significant. Three patients discontinued voriconazole due to side-effects. Conclusion: Voriconazole is an effective and safe oral agent for IFI prophylaxis during induction therapy of AML. Availability of generic equivalents makes this a more economical alternative to posaconazole.

Keywords

Acute myeloid leukemia - anti-fungal prophylaxis - fluconazole - invasive fungal infection - voriconazolePublication History

Article published online:

12 July 2021

© 2016. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Background:

Antifungal prophylaxis (AFP) reduces the incidence of invasive fungal infections (IFIs) during induction therapy of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Posaconazole is considered the standard of care. Voriconazole, a generic cheaper alternative is a newer generation azole with broad anti-fungal activity. There is limited data on the use of voriconazole as a prophylactic drug.

Materials and Methods:

A single-center, prospective study was performed during which patients with AML undergoing induction chemotherapy received voriconazole as AFP (April 2012 to February 2014). Outcomes were compared with historical patients who received fluconazole as AFP (January 2011-March 2012, n = 66).

Results:

Seventy-five patients with AML (median age: 17 years [range: 1-75]; male:female 1.6:1) received voriconazole as AFP. The incidence of proven/probable/possible (ppp) IFI was 6.6% (5/75). Voriconazole and fluconazole cohorts were well-matched with respect to baseline characteristics. Voriconazole (when compared to fluconazole) reduced the incidence of pppIFI (5/75, 6.6% vs. 19/66, 29%; P < 0.001), need to start therapeutic (empiric + pppIFI) antifungals (26/75, 34% vs. 51/66, 48%; P < 0.001) and delayed the start of therapeutic antifungals in those who needed it (day 16 vs. day 10; P < 0.001). Mortality due to IFI was also reduced with the use of voriconazole (1/75, 1.3% vs. 6/66, 9%; P = 0.0507), but this was not significant. Three patients discontinued voriconazole due to side-effects.

Conclusion:

Voriconazole is an effective and safe oral agent for IFI prophylaxis during induction therapy of AML. Availability of generic equivalents makes this a more economical alternative to posaconazole.

INTRODUCTION

Invasive fungal infection (IFI) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality during induction chemotherapy in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML).[1] Up to a quarter of patients develop IFI during induction therapy of AML with an associated mortality of 40% (candidiasis and aspergillosis) to 70% (fusariosis and zygomycosis).[2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9] One of the reasons for the high mortality could be the difficulty in establishing the diagnosis and the consequent delay in instituting definitive therapy.[10,11,12] Hence, it is the standard practice to use prophylactic anti-fungal agents in this setting.

One of the first agents used was fluconazole that was effective and safe.[8,9,13] But fluconazole lacked activity against molds,[14] which are a major cause of IFI during therapy of AML.[15] However, subsequent studies with itraconazole and various formulations of amphotericin B failed to demonstrate superiority vis a vis fluconazole.[13,16] In 2006, posaconazole was approved as antifungal prophylactic agent during induction therapy of AML.[17] This approval was based on an international randomized trial comparing posaconazole to fluconazole as a prophylactic agent during the induction therapy of AML where posaconazole demonstrated reduced occurrence of IFI and reduced mortality associated with IFI in these patients.[18] At present, most of the guidelines recommend posaconazole as the agent of choice for prophylaxis during induction therapy of AML.[19,20]

Despite the approval and subsequent availability of posaconazole, there was limited use of posaconazole in our hospital due to the high cost. As we had a very high incidence, morbidity and mortality associated with IFI at our center with the use of fluconazole prophylaxis, an effective alternative was needed. Voriconazole, another new generation oral azole, with a wide spectrum of anti-fungal activity (including Aspergillus sp.) was approved for the treatment of IFI in patients with neutropenia.[21,22] At our center, voriconazole was cheaper than posaconazole (mainly due to the availability of generic equivalents). The proven activity against the common agents causing IFI and the economical pricing made voriconazole an attractive proposition as a preventive agent. Beginning in 2011, we started using voriconazole as the prophylactic agent for all our patients with AML undergoing induction therapy. We prospectively followed these patients to understand the efficacy and safety of voriconazole as anti-fungal prophylaxis (AFP) during induction chemotherapy of AML. The results were compared with patients in the previous years that received similar treatment but received prophylaxis with fluconazole.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a single center, prospective observational study of patients with AML undergoing induction chemotherapy and receiving voriconazole as AFP. All patients were treated at the Department of Medical Oncology, Cancer Institute (WIA), Adyar, Chennai between April 2012 and February 2014. The outcomes were compared with the historical data of similar patients who received fluconazole as AFP.

Inclusion

All patients of AML (pediatric and adult) who had undergone induction chemotherapy at our center during the study period were included. Patients with a preexisting diagnosis of proven/probable/possible (ppp) IFI (prior to starting induction treatment) or those with significant renal or hepatic dysfunction, who were ineligible for prophylactic voriconazole, were excluded from analysis. Before enrollment, written informed consent was obtained from each patient or the patient's parent or legal guardian for allowing collection of data from the patient. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institution.

Anti-fungal prophylaxis and management of febrile neutropenia

All patients started voriconazole on day 1 of induction chemotherapy of AML. Voriconazole was taken by the patient on an empty stomach (1 h before or 2 h after food). The dose of voriconazole was 200 mg orally twice a day in adults and 4 mg/kg/dose (rounded to nearest 50 mg) twice a day in pediatric patients (maximum 200 mg BID). Drug level monitoring was not performed in any of our patients.

When patients developed fever, cultures were obtained and empiric antibacterial agents (first line treatment with a combination of cefoperazone-sulbactam and amikacin, second line with piperacillin-tazobactam and the third line with meropenem; teicoplanin was added in patients with suspected/proven Gram-positive infection or hypotension) were initiated. High-resolution computed tomography scan (HRCT) of the thorax was done in patients with chest symptoms or in those with unresponsive fever after 5-7 days of antibiotics.

Diagnosis and management of invasive fungal infections

Whenever a diagnosis of pppIFI was made, voriconazole was discontinued and therapeutic intravenous amphotericin B deoxycholate (1 mg/kg) or intravenous caspofungin (70 mg on day1 and 50 mg/day from day 2) was started. In addition, empirical antifungal therapy (for unresponsive fever after 5-7 days of appropriate antibiotics without any evidence of pppIFI) was considered on a case-by-case basis at the discretion of the attending or consultant physician. Voriconazole was discontinued and changed to other anti-fungal agent when there was grade 2 or more side effects attributable to voriconazole. In all other patients, voriconazole was continued until the absolute neutrophil count was more than 1500 for 3 consecutive days.

Historical cohort

Prior to initiating this study with voriconazole prophylaxis, all patients undergoing induction therapy were treated with fluconazole as the prophylactic agent at the dose of 6 mg/kg/day, capped at 300 mg/day. The data of these patients treated between January 2011 and March 2012 was obtained retrospectively from the medical records.

End points and statistical analysis

The primary end point was the incidence of proven/probable/possible IFI during the induction chemotherapy.[23] Secondary end points analyzed were: The need to start empirical antifungal therapy, time to start antifungal therapy, mortality due to IFI, mortality due to any reason, and incidence of adverse events possibly or probably related to voriconazole. Side effects were graded as per NCI toxicity criteria version 3.0[24] whenever feasible.

The categorical end points were compared between patients receiving voriconazole and fluconazole using the Fischer exact test. Student's t-test was used to compare the time-dependent variables. All analysis was carried out using SPSS software version 17 (SPSS Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

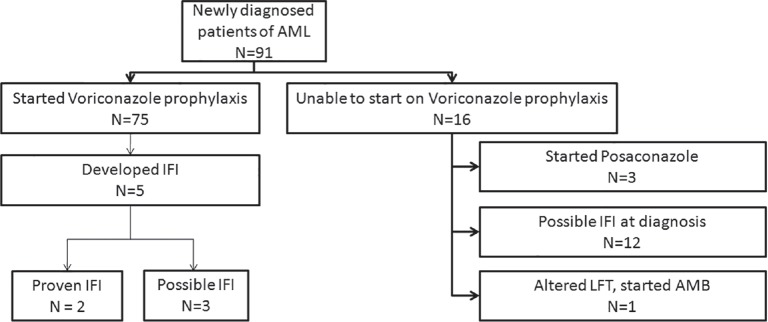

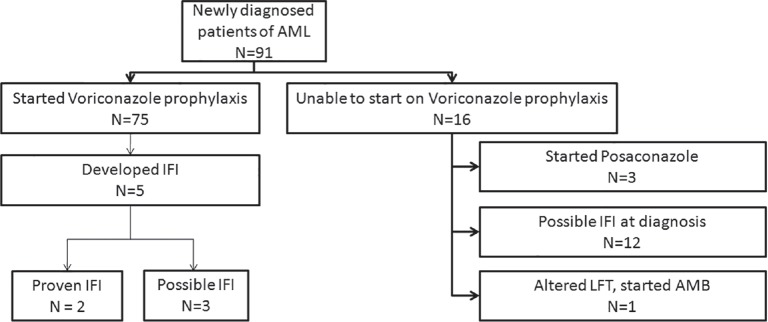

Ninety-one patients with AML started induction therapy during the study period. Seventy-five of these started on prophylactic voriconazole. Sixteen patients couldnot start prophylactic voriconazole due to various reasons [Figure 1]. Among these, there were 12 patients who presented with features of possible IFI at diagnosis and were initiated on therapeutic anti-fungal and were not eligible for inclusion in the prophylactic treatment.

| Fig. 1 Flow diagram showing all the patients of acute myeloid leukemia treated in the study period and their outcomes with respect to development of invasive fungal infections

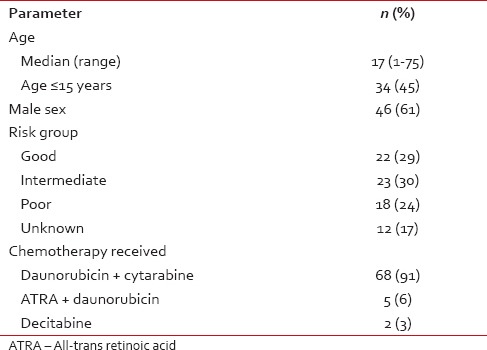

The median age of the study population was 17 years (range 1-75 years) with a male:female ratio of 1.6:1 [Table 1]. Most patients (87%) received daunorubicin + cytarabine-based induction therapy.

Table 1

Baseline characteristics (n = 75) of patients who received voriconazole prophylaxis

Efficacy and toxicity of voriconazole

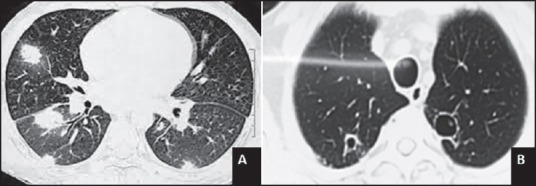

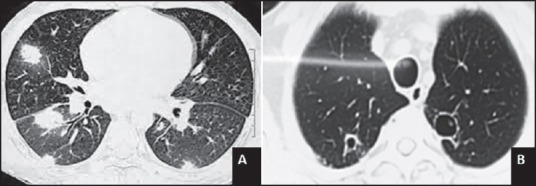

ppp fungal infection developed in 5/75 (6.6%) patients. Two of these had proven IFI (blood culture isolated candidiasis, one had Candida krusei, and one had Candida glabrata). Three others had possible IFI based on clinical and radiological features [Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1].

| Fig. 2 Lung nodule showing with halo sign (a) and bilateral opacities with cavitations (b)

Supplementary Table 1

Characteristics of patients who developed invasive fungal infection (n = 5) while on voriconazole prophylaxis

Click here for additional data file.Twenty-one patients started empiric anti-fungal therapy. Hence, a total of 26/75 (34%) patients started therapeutic (empiric + pppIFI) antifungals. The mean time to start of therapeutic antifungals was 16 days. The mortality due to IFI was 1/75 while 7/75 patients died due to other causes [Supplementary Table 2].

Supplementary Table 2

Characteristics of patients who expired (n = 8)

Click here for additional data file.Voriconazole was associated with visual disturbances in 7/75 (9.3%) patients. Most of these patients described transient blurring of vision, photophobia or photopsias. Most of these symptoms were mild and transient and did not require interruption. Three patients (4%) developed visual hallucinations that necessitated discontinuation in one patient. In the other two, symptoms gradually resolved without specific interventions. Three patients developed hepatotoxicity (elevation of bilirubin) - this was NCI CTC version 3.0 Grade 3 in two patients and required discontinuation. These patients were switched to prophylactic amphotericin B. Hepatotoxicity in these two patients was noted on day 2 and day 14 of therapy respectively. In both these patients, liver functions reverted to normal within 3 days of stopping voriconazole. No other Grade 3/4 toxicity attributable to voriconazole was noted. In total, three patients discontinued voriconazole due to side effects.

Historical data of patients using fluconazole as anti-fungal prophylaxis

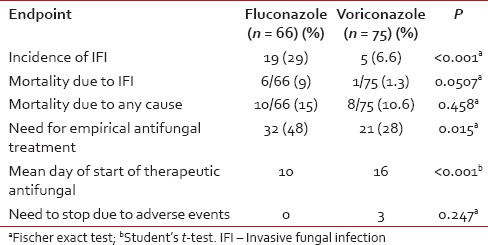

Sixty-six patients with AML took treatment at our institute between January 2011 and March 2012 and received fluconazole as prophylaxis. Age, sex, risk groups, and treatment protocols were comparable to the cohort of patients treated with voriconazole [Supplementary Table 3]. Nineteen out of 66 patients (29%) developed pppIFI (3 proven, 16 possible). Of these, six patients died due to IFI and total 10 patients died due to other causes. In addition, 32 patients (48%) needed empiric anti-fungal treatment. Hence, 51/66 (77%) needed to start on therapeutic (empric+pppIFI) antifungals. Mean time to start of antifungals was 10 days.\

Supplementary Table 3

Comparison of baseline variables between patients receiving fluconazole and voriconazole

On comparing the outcomes between patients receiving voriconazole and fluconazole, it was found that patients treated with voriconazole had a significantly lesser incidence of pppIFI and lesser need for empiric anti-fungal treatment and also had a much longer time to initiate therapeutic antifungal drugs [Table 2].

Table 2

Comparison of voriconazole and fluconazole as antifungal prophylaxis agents during induction therapy of acute myeloid leukemia

DISCUSSION

This is one of the few studies prospectively evaluating the efficacy of voriconazole as AFP during induction therapy of AML. Voriconazole was a well-tolerated and extremely effective as a prophylactic agent and reduced the incidence of IFI to 6.6% (from 25% in an earlier cohort who received fluconazole). The incidence of pppIFI was only 6.6%. In addition, voriconazole also reduced the number of deaths due to IFI, need of empirical antifungal treatment and delayed the start of anti-fungal treatment.

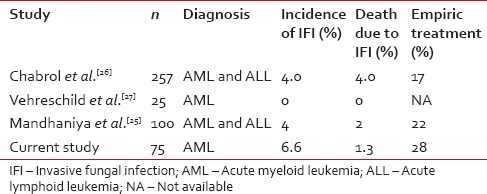

Three other studies [Table 3] have reported on the use of voriconazole as an antifungal prophylactic agent.[25,26,27] The incidence of IFI ranged from 0% to 4% in these studies. We saw an incidence of 6.6% in our patients which is comparable to that reported by Mandhaniya et al.[25] and Chabrol et al.[26] but higher than that reported by Vehreschild et al. However the study by Vehreschild et al.[27] had very small number of patients which limits interpretation. On comparing secondary end points, the need for empirical antifungal treatment was 28% in our study that was 17% and 22% in studies by Chabrol et al. and Mandhaniya et al. respectively, which is comparable.[25,26]

Table 3

Comparison of studies using voriconazole as antifungal prophylaxis during induction therapy of acute leukemia

The incidence of IFI with voriconazole among our patients appears to be slightly higher than the remarkable 2% reported by Cornely et al. in the registration trial of posaconazole.[18] However, cross-trial comparisons can be fallacious because of the variability in end points and the variable settings in which they are performed. Cornely et al. considered only “proven” and “probable” cases as IFI, whereas in our study proven, “possible” cases were also included. Moreover, the study by Cornely et al. was conducted in a Western environment with a temperate weather where the incidence of IFI could be much lesser compared to the tropical conditions in India.[28,29] In fact, the incidence of IFI in the study by Cornely et al. in the control arm using fluconazole was only 6% (compared to 25% with the use of fluconazole at our center).

An important concern with voriconazole was its potential for toxicity and drug interactions. However, most of the medicines used during AML therapy (including many antibacterials) don’t have clinically significant interactions with voriconazole, and this is well-established as a therapeutic agent in these patients. We found that voriconazole was very well-tolerated, and most of the side effects were mild and as expected from earlier reports.[30,31,32,33] Drug-related serious adverse events leading to discontinuation of voriconazole prophylaxis was 4% in our study while in the study by Mandhaniya et al. it was 2% and 14% in the study by Chabrol et al.[25,26] Serious adverse events possibly or probably related to posaconazole have been reported in up to 6% of patients.[18]

CONCLUSION

Our patients did not have access to serological tests that could have led to underdiagnosis of “probable” IFI. Furthermore, HRCT scans at baseline were performed routinely in the voriconazole cohort while they were performed only in the symptomatic patients in the historical controls. This may have led to these patients receiving AFP rather than therapy. However, we had a proactive approach to performing diagnostic high-resolution computed tomography scans of the chest and nasal sinuses to enable early diagnosis of fungal infections. We did not monitor voriconazole drug level that is recommended by some authors.[34,35] Though the comparator cohort receiving fluconazole was historical, both groups were comparable and received similar treatment and supportive care medicines, making the comparisons relevant. This is one of the few studies to clearly show the efficacy and safety of voriconazole as a prophylactic agent during AML therapy and clearly shows its superiority versus fluconazole. Only a randomized trial can answer the question of whether it can be equivalent to posaconazole. However, in a resource-constrained setting with a high incidence of IFI, generic voriconazole affords an effective and cheaper alternative.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

| Fig. 1 Flow diagram showing all the patients of acute myeloid leukemia treated in the study period and their outcomes with respect to development of invasive fungal infections

| Fig. 2 Lung nodule showing with halo sign (a) and bilateral opacities with cavitations (b)

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share