Thymoma masquerading as transfusion dependent anemia

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2016; 37(04): 296-299

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/0971-5851.195729

Abstract

Pure red cell aplasia (PRCA) is a known entity in clinical medicine. Patients are often transfusion dependent for their whole life. Ascertaining its etiology is always a herculean task. We received a similar transfusion-dependent patient, who on evaluation was found to have thymoma as an etiological factor. Thymoma presenting as PRCA is seen in 2%–5% patients and evaluating PRCA for thymoma is seen in 5%–13% patient. As per the WHO histopathological classification, thymoma has six types and Type A is associated with PRCA and Type B is associated with myasthenia gravis. This correlation was not seen in our patient, who had Type B thymoma. Surgical resection of thymus improves 30% of PRCA and rest needs immunosuppression. Our patient was not the surgical candidate, and hence he was put on chemotherapy.

Keywords

Compound mean action potential - large granular leukemia - myasthenia gravis - pure red cell aplasia - repeated nerve stimulationPublication History

Article published online:

12 July 2021

© 2016. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Pure red cell aplasia (PRCA) is a known entity in clinical medicine. Patients are often transfusion dependent for their whole life. Ascertaining its etiology is always a herculean task. We received a similar transfusion-dependent patient, who on evaluation was found to have thymoma as an etiological factor. Thymoma presenting as PRCA is seen in 2%–5% patients and evaluating PRCA for thymoma is seen in 5%–13% patient. As per the WHO histopathological classification, thymoma has six types and Type A is associated with PRCA and Type B is associated with myasthenia gravis. This correlation was not seen in our patient, who had Type B thymoma. Surgical resection of thymus improves 30% of PRCA and rest needs immunosuppression. Our patient was not the surgical candidate, and hence he was put on chemotherapy.

INTRODUCTION

Acquired pure red cell aplasia (PRCA) is a rare, generally chronic condition of profound anemia characterized by a severe reduction in the number of reticulocytes in the peripheral blood and the virtual absence of erythroid precursors in the bone marrow. All other cell lineages are present and appear morphologically normal. PRCA is of two types as primary and secondary (acquired). Acquired PRCA has wide diverse etiology, ranging from lymphoproliferative disorders till infections. These include:

- Drugs - Phenytoin, trimethoprim, zidovudine, chlorpropamide, recombinant erythropoietin, and mycophenolate mofetil

- Infections - Parvovirus B19, HIV, and viral hepatitis

- Autoimmune disorders - Systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, hemolytic anemia, and allogeneic stem cell transplant

- Lymphoid malignancies - Chronic lymphocytic leukemia, large granular leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, and myeloma

- Myeloid malignancies - Chronic myeloid leukemia, myelofibrosis, and prodrome of myelodysplastic syndrome

- Other causes - Thymoma, pregnancy, idiopathic, etc.

A thymoma is present in approximately 5% of patients with PRCA.[1,2] A number of cases of coexisting myasthenia gravis (MG) and PRCA have been described in the literature; all were thymoma associated except for one with thymic hyperplasia.[3]

As the onset of anemia in PRCA is insidious, patients may have little signs and symptoms until the anemia becomes severe. Extreme pallor or decreased exercise tolerance may be the first sign of this disorder in a previously healthy individual. Anemia is often severe and is normocytic and normochromic. Reticulocytes are markedly decreased and are often absent. Bone marrow examination shows normal overall cellularity, with complete or virtually complete absence of red cell precursors.

There is a well-documented association of PRCA with thymoma, with an incidence of about 5%.[1] Even if a thymoma is present, surgical resection only occasionally results in improvement or cure of the PRCA, and additional treatment (e.g., glucocorticoids, cyclosporine, and cyclophosphamide) is needed in most cases.[1,2,4,5]

Even though it is not very common to have acquired PRCA, documenting its etiology needs extensive and systemic workup, which involves multispecialty approach. We are reporting a similar case who was treated outside our hospital for many years with blood products and hematinic and later got documented thymoma as an etiological cause.

CASE REPORT

A 60-year-old gentleman, who was normotensive, nondiabetic, and euthyroid, presented to our outpatient clinic with features of symptomatic anemia in the form of malaise and poor exercise tolerance. There was no history of apparent blood loss, bleeding diathesis, or poor intake. There was also no history of muscle weakness, diplopia, speech fatigue, or any surgery. He gave a history of repeated blood transfusions, ten such events he could remember and was on iron supplements since 6 years. On clinical examination, he had severe pallor and mild splenomegaly, rest of examination was unremarkable.

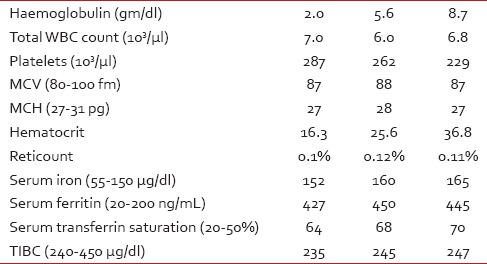

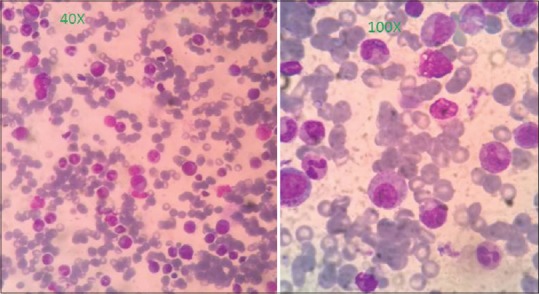

On evaluation, he had hemoglobin of 2 g/dl with normal red cell indices and raised serum iron indices [Table 1]. His liver function test, kidney function test, lactate dehydrogenase, electrolytes, calcium, and phosphorous were normal. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) and lower GI endoscopy was normal. Bone marrow aspiration was done, which revealed hypercellular marrow with absent erythroid precursors, abundant iron stores with normal other cell lines [Figure 1]. This all was suggestive of PRCA. Further evaluation carried out to look for causes of acquired PRCA.

Table 1

Laboratory parameters of patient

| Fig. 1 Bone marrow revealing absence of erythroid precursors

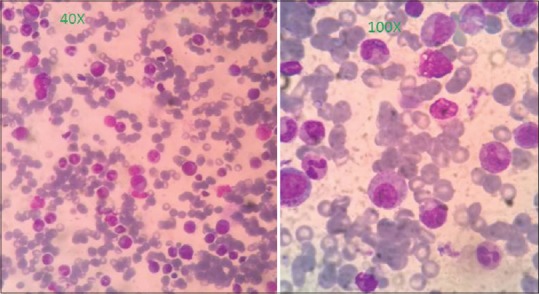

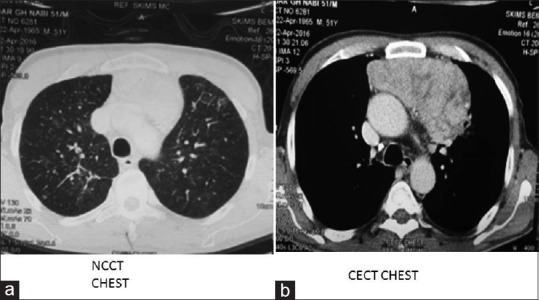

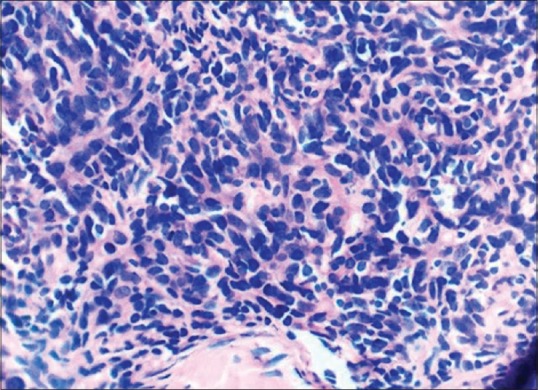

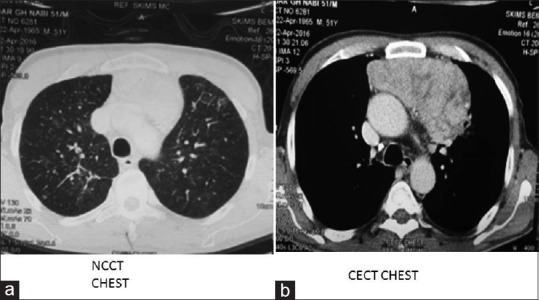

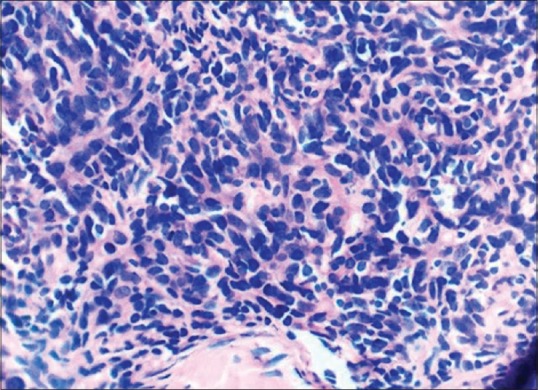

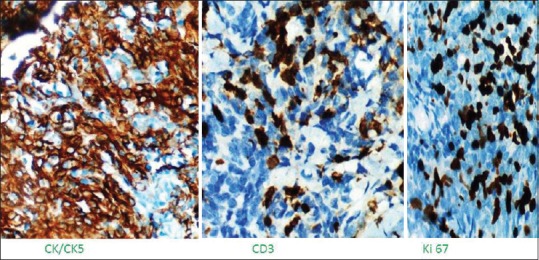

Hepatitis B, C, and A was negative as was Epstein–Barr virus and cytomegalovirus serology. Both IgG and IgM for Parvovirus B19 was absent in serum. Connective tissue disease markers such as antinuclear antibody, dsDNA, and rheumatoid factor levels were normal. Chest X-ray had mild mediastinal widening. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan was done which showed large anterior mediastinal mass with close approximation to great vessels [Figure 2]. Then, CT-guided biopsy of mass was carried out, which was consistent with WHO Class B1 thymoma [Figure 3]. Further immunohistochemistry was carried out, which revealed CK 5/6 positive in plump oval cells, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase, and CD3 positive in lymphocytes and Ki67 of 50% [Figure 4]. Clinically, as per Masaoka staging, it was between stages IIB to III. Further workup was done for myasthenia, which was negative in this patient. He had no decremental patterns in CMAP on RNS. A final diagnosis of acquired PRCA due to thymoma was made.

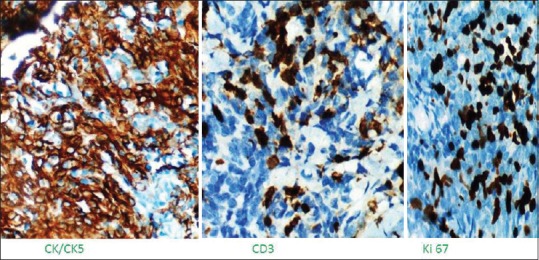

| Fig. 2 Computed tomography of chest revealing the anterior mediastinal mass. (a) noncontrast. (b) Contrast

| Fig. 3 Histopathological examination (HPE) of anterior mediastinal mass revealing small oval to spindle cells admixed with lymphocytes consistent of WHO type B1 thymoma

| Fig. 4 Immunohistochemistry revealing thymoma positive for CK5, CD3, and Ki67 is 40%

As for as management was concerned, PRCA is treated with steroids or immunosuppressants, but some patients go into remission on surgery only. Patient was not a surgical candidate as he would have persisted with gross residual disease, so we put this patient on multiagent chemotherapy with cisplatin, adriamycin, and cyclophosphamide. Patient received multiple transfusions so that he was made fit for chemotherapy. Plan is to give four cycles of chemotherapy followed by surgery with or without adjuvant radiotherapy.

DISCUSSION AND REVIEW OF LITERATURE

PRCA, a disorder first characterized in 1922,[6] is a syndrome characterized by severe normochromic, normocytic anemia associated with reticulocytopenia and absence of erythroblasts from an otherwise normal bone marrow. The acquired form of PRCA presents either as an acute self-limited disease, predominantly seen in children or as a chronic illness that is more frequently seen in adults. As was seen in our patient, he also presented with chronic anemia, had got multiple blood transfusions till we received him. Depending on the cause, the course can be acute and self-limiting or chronic with rare spontaneous remissions.[7,8]

In approximately 60% of patients with PRCA, their serum and its IgG fraction inhibit the growth of patient and normal erythroid progenitors in vitro.[1,9] The target antigen is usually not known; in a few cases, however, the IgG fraction contains an inhibitor of erythropoietin. In other cases of autoimmune PRCA, suppression of erythropoiesis seems to be mediated by T-lymphocytes.[1,10] In our patient, we could not trace out the type of immunological damage. The net result of the immune attack in PRCA, which is characterized by marked reduction or absence of all recognizable red cell precursors in the bone marrow and absence of reticulocytes in the peripheral blood. In our patient, net hemoglobin was 2.0 g/dl with normal red cell indices and almost absent reticulocytes in peripheral blood and absent erythroblasts in bone marrow.

MG and PRCA are occasionally associated with thymoma. MG appears in about 20%–40% of patients with thymoma, and PRCA develops in about 2%–5% of those patients.[11] On the other hand, thymoma is detected in 10%–17% of patients with MG and in 5%–13% of patients with PRCA.[12,13] However, the simultaneous occurrence of MG, PRCA, and thymoma is extremely rare. In our patient, chest X-ray had mild mediastinal widening, but CT showed large mediastinal mass with close relation with large arteriovenous system. As per the WHO histological classification, thymoma is divided into six types as Type A, AB, B1, B2, B3, and C. Our patient had B1 histology pattern, consisting of lymphocytic rich predominantly cortical organoid cells. It has been seen that Type A is associated with PRCA and Type B with MG, but in our patient, this correlation was not seen. Patient was inoperable at beginning, and likely fitted in clinical stage II to III and complete surgical excision was not possible. Hence, our patient was put on chemotherapy at outset and plan is thymectomy after few cycles of chemotherapy.

It has been seen that PRCA improves in 30% of patients after complete thymectomy, and complete surgical excision with adjacent structures is possible in 88% of patients.[14,15] There are several options for inducing remission of PRCA after surgery, but many patients with acquired PRCA require immunosuppressive therapy to maintain remissions. Corticosteroids, cyclosporin A, and cyclophosphamide are almost equally effective for inducing remissions of PRCA, but the most important difference between these agents is the feasibility of long-term maintenance. Considering the recurrent nature of acquired PRCA, it has been suggested cyclosporin A as first-line therapy for these patients at a dose of 2.5–3 mg/kg twice daily to achieve trough cyclosporin A (CsA) levels of 150–250 ng/ml for a maximum of 3–4 months. This trough CsA level has been empirically determined according to a consensus from a multicenter randomized study in Japan for aplastic anemia.[16] Maintenance therapy with CsA is a requisite for most patients to prevent relapse. Prognosis of thymoma is related to stage of presentation, presence or absence of complete resection, and histological subtype. Subtype A and AB behaves as benign tumor, subtype B (B1 and B2) behaves as low-grade tumor, and subtype B3 and C behaves as thymic carcinoma.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

This work has been acknowledged by our reviewers, as this is the first time we saw acquired PRCA presenting syndrome of thymoma, even though it is not that uncommon, but rarely seen in our patient population.

| Fig. 1 Bone marrow revealing absence of erythroid precursors

| Fig. 2 Computed tomography of chest revealing the anterior mediastinal mass. (a) noncontrast. (b) Contrast

| Fig. 3 Histopathological examination (HPE) of anterior mediastinal mass revealing small oval to spindle cells admixed with lymphocytes consistent of WHO type B1 thymoma

| Fig. 4 Immunohistochemistry revealing thymoma positive for CK5, CD3, and Ki67 is 40%

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share