Synovial Sarcoma of Anterior Abdominal Wall

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2020; 41(02): 269-272

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/ijmpo.ijmpo_143_18

Abstract

Primary synovial sarcoma arising in the anterior abdominal wall is rare and is a rare extra-articular tumor site. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis of anterior abdominal wall masses. It is a rare malignant mesenchymal tumor. It commonly occurs in adults in the extremities in close association with joint capsule, tendon sheaths, bursae and fascial structures. Synovial sarcoma is derived from multipotent stem cells, which can differentiate into mesenchyma and epithelial structures. Three subtypes are described histologically -biphasic, monophasic, and poorly differentiated synovial sarcoma. We report a case of a 40-year-old male patient presented with swelling over the anterior abdominal wall on the right side in the lower abdomen for 1 month which was rapidly increasing in size. An ultrasound followed by computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen were performed for knowing the extent of the tumor. Immunohistochemistry was suggestive of monophasic synovial sarcoma.

Keywords

Abdominal wall tumor - soft-tissue sarcoma - synovial sarcomaPublication History

Received: 30 June 2018

Accepted: 12 September 2018

Article published online:

23 May 2021

© 2020. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Primary synovial sarcoma arising in the anterior abdominal wall is rare and is a rare extra-articular tumor site. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis of anterior abdominal wall masses. It is a rare malignant mesenchymal tumor. It commonly occurs in adults in the extremities in close association with joint capsule, tendon sheaths, bursae and fascial structures. Synovial sarcoma is derived from multipotent stem cells, which can differentiate into mesenchyma and epithelial structures. Three subtypes are described histologically -biphasic, monophasic, and poorly differentiated synovial sarcoma. We report a case of a 40-year-old male patient presented with swelling over the anterior abdominal wall on the right side in the lower abdomen for 1 month which was rapidly increasing in size. An ultrasound followed by computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen were performed for knowing the extent of the tumor. Immunohistochemistry was suggestive of monophasic synovial sarcoma.

Keywords

Abdominal wall tumor - soft-tissue sarcoma - synovial sarcomaIntroduction

Synovial sarcoma is a rare malignant mesenchymal tumor. It commonly occurs in adults in the extremities in close association with joint capsule, tendon sheaths, bursae, and fascial structures. It is the fourth most common type of soft-tissue sarcoma following rhabdomyosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiosarcoma, and liposarcoma. Nearly 80%–90% synovial sarcoma occurs in the extremities in the middle-aged patient, close to large joint, particularly the knee joint in the popliteal fossa. Synovial sarcoma arising in the anterior abdominal wall is rare with only 47 cases reported in the literature. Synovial sarcoma in anterior abdominal wall occurs with greater frequency in females while synovial sarcoma in extremities or the neck occurs with greater frequency in males. Primary synovial sarcoma of anterior abdominal wall (SSAW) is a rare extra-articular tumor site. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis of the anterior abdominal wall masses.[1]

Case Report

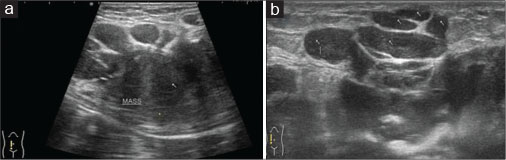

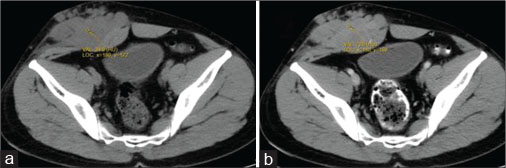

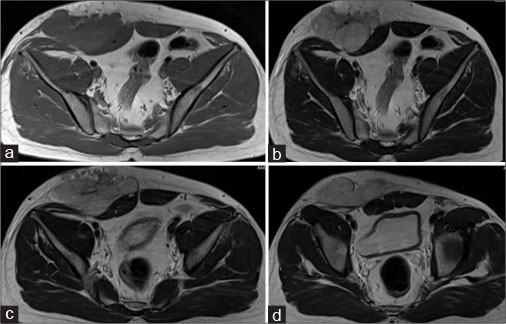

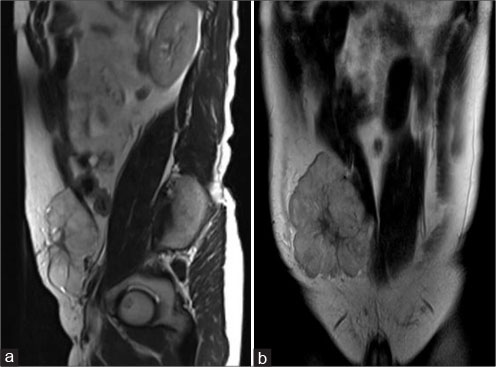

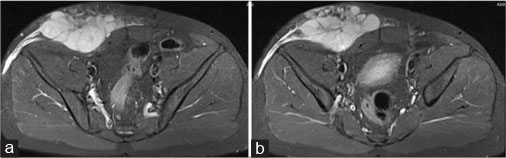

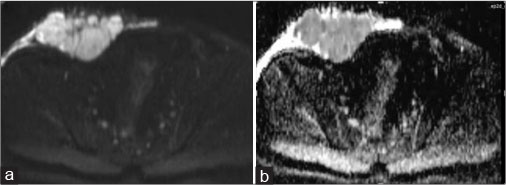

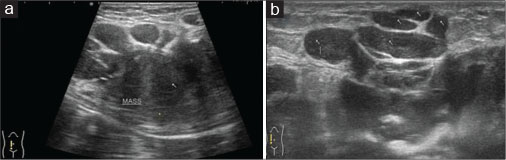

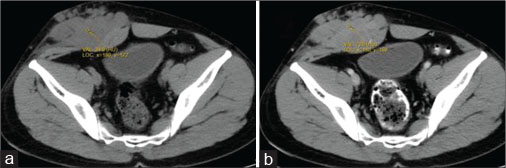

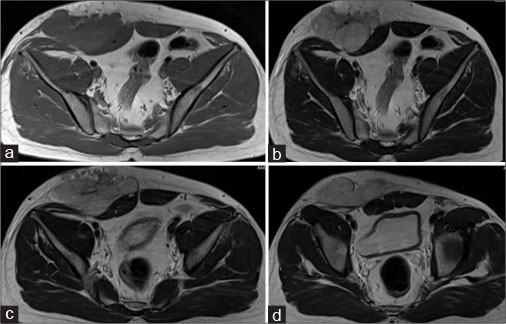

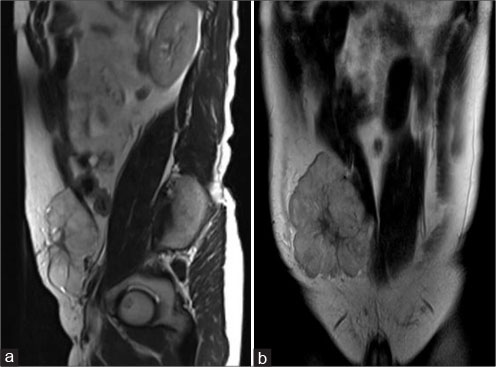

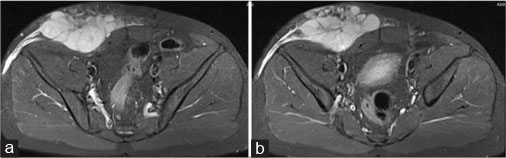

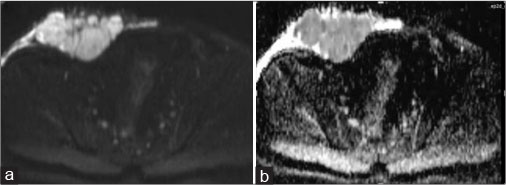

A 40-year old male patient presented with swelling over the anterior abdominal wall on the right side in lower abdomen for 1 month which was rapidly increasing in size. There was a history of weight loss. The mass was painless. The ultrasonography showed a large, well-defined solid mass with lobulated outlines in anterior abdominal wall in the right paraumbilical and hypogastric region [Figure 1]. The mass was seen in the subcutaneous plane, causing extrinsic compression on adjoining right rectus abdominis and external oblique muscle. It was predominantly hypoechoic with small areas of the necrosis in its center and showed mild vascularity on color Doppler. No calcification was seen. Plain and contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT)-scan of the abdomen and pelvis was performed. A large, well defined solid mass with lobulated outline measuring approximately 96 mm × 38 mm × 98 mm in transverse, anteroposterior and craniocaudal dimension was noted in the anterior abdominal wall on the right side in right iliac region extending to hypogastric region. It was slightly hypodense with respect to muscle on the plain study with a CT value of 35–45 HU and showed a mild heterogeneous enhancement in contrast study (CT value 55–65 HU). No calcification was noted. The mass was in subcutaneous plane and was extending anteriorly up the skin. Posteriorly, it was causing mass effect on the right rectus abdominus and adjoining external oblique and internal oblique muscles which were compressed and displaced posteriorly with obliteration of intervening fat planes [Figure 2]. An enhancing vessel was noted in the right rectus abdominus extending into the mass suggestive of neovascularity. No intra-abdominal extension was noted. Rest of the abdominal wall appeared normal. No hepatic or adrenal metastases, intra-abdominal lymphadenopathy noted. On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the mass appeared slightly hyperintense with respect to muscle on T1-weighted image, heterogeneously hyperintense on T2-weighted image (T2WI), and hyperintense on short tau inversion recovery and showed restricted diffusion on diffusion-weighted imaging with low apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values (ADC = 800). It was causing mass effect on the right rectus abdominus and adjoining external oblique and internal oblique muscles [Figure 3] [4] [5] [6].

| Figure 1: Ultrasound of the anterior abdominal wall with linear probe showing well-defned solid hypoechoic mass with lobulated outlines in the right iliac fossa in subcutaneous plane (a) causing extrinsic compression and posterior displacement of abdominal wall muscles (b)

| Figure 2: Computed axial tomography of abdomen - plain (a) and contrast (b) showing well-definedsolid mass with lobulated outlines in the right iliac fossa and hypogastric region in subcutaneous plane causing extrinsic compression and posterior displacement of abdominal wall muscles appearing slightly hypodense on plain study (a) showing heterogeneous enhancement in contrast (b)

| Figure 3: Magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen - axial T1 (a), axial T2 (b-d) showing well-definedsolid mass with lobulated outlines in the right iliac fossa and hypogastric region in subcutaneous plane causing extrinsic compression and posterior displacement of abdominal wall muscles appearing slightly hyperintense on the T1-weighted image and hyperintense on T2-weighted image

| Figure 4: Magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen - sagittal T2 (a), coronal T2 (b) showing well-definedsolid mass with lobulated outlines in the right iliac fossa and hypogastric region in subcutaneous plane causing extrinsic compression and posterior displacement of abdominal wall muscles appearing hyperintense on T2-weighted image

| Figure 5: Magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen - axial short tau inversion recovery (a and b) showing well-definedhyperintense solid mass with lobulated outlines in the right iliac fossa and hypogastric region in subcutaneous plane causing extrinsic compression and posterior displacement of the abdominal wall muscles

| Figure 6: Magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen - axial diffusion-weighted imaging (a), apparent diffusion coefficien (b) showing restricted diffusion on diffusion-weighted imaging with low apparent diffusion coefficient value

Biopsy was suggestive of round cell sarcoma. On immunohistochemistry, tumor showed predominantly monophasic growth pattern and was composed of spindloid cells arranged in cellular and hypocellular fashioned. They showed diffuse and strong positivity for Vimentin, BCL-2, and MIC-2. These cells showed focal priority for CK and EMA and were negative for SMA, Desmin, and S-100 protein. The findings were suggestive of monophasic synovial sarcoma.

Discussion

Synovial sarcoma accounts for 8% of all primary soft-tissue malignancy worldwide. They usually present at 15–40 years of age and frequently seen in adolescent and young adults. There is no gender, race or ethnic predilection. It presents as a palpable slow growing mass. Delay in diagnosis often occurs due to gradual onset. Histologically, they do not resemble synovial structures. They are named so due to the similarity between synovial sarcoma tumor cells and primitive synoviocytes. Synovial sarcoma is derived from multipotent stem cells. These can differentiate into mesenchyma and epithelial structures. Histologically, three subtypes are described-biphasic, monophasic, and poorly differentiated synovial sarcoma. Monophasic synovial sarcomas the most common subtype (50%–60%) are entirely composed of spindle cells. Biphasic synovial sarcoma (20%–30% of cases) has epithelial and spindle cell component in varying proportions. The epithelial cells classically found are glands. The poorly differentiated synovial sarcoma (15%–25% of cases) shows small blue round cell morphology with high mitotic activity. Synovial sarcoma can be graded according to mitotic index, necrosis, and tumor differentiation. Synovial sarcoma should be usually considered high-grade sarcomas.[2]

Synovial sarcoma is commonly seen in lower extremity in 70% of cases, other rare sites are head and neck (5%), trunk (8%), and abdomen and retroperitoneum (7%).

Conventional radiography in synovial sarcoma can be normal or shows soft-tissue mass. Nearly 20% cases show calcifications. Ultrasound appearance is nonspecific and seen as a solid heterogeneous mass with heterogeneous echotexture with irregular margins. It helps in USG-guided biopsy. On CT scan, the mass appears as a well-circumscribed mass with heterogeneous density with attenuation value slightly lower than muscle. Contrast study often shows heterogeneous enhancement. Small low attenuation areas were noted within the mass represents the necrosis or cystic changes. Punctate calcification can be seen in 30% cases, usually in the periphery of the mass. MR imaging is the modality of choice for its diagnosis. On T1-weighted spin echo MR images, it appears as a multilobulated soft-tissue intensity heterogeneous mass with signal intensity equal to or higher that of muscle. On T2-weighted spin echo MR images, the mass appears heterogeneous with high signal intensity. Areas of hemorrhage, cystic changes, and fluid levels may be seen. A triple sign may be seen on T2WI showing triple signal pattern, characterized by intermixed areas of high, intermediate and low-signal intensity. Aggressiveness of the tumor can be judged by the detection of local invasion such as muscle invasion, underlying bony involvement, and neurovascular encasement. Contrast-enhanced MRI shows heterogeneous enhancement pattern.[2]

Only 47 cases of synovial sarcoma of the anterior abdominal wall (SSAW) have been reported in the English journal.[3] Its incidence is 2.5 per lakhs. Metastases can be seen in 16%–25% cases on initial presentation, which commonly occurs in lung and less commonly in lymph nodes and bones. The majority of metastases occurs in the first 2–5 years of treatment. Doppler my show increase internal vascularity. Although imaging findings of SSAW are not pathognomonic, eccentric, or peripheral calcification can be seen in 30% of cases. Necrosis and hemorrhage occur commonly. Ultrasonography can detect a complex honeycomb echotexture.[4] MRI is useful in detecting extension, multilobulation on T2WI, planning treatment, and tumor response to chemotherapy.[3]

Synovial sarcoma does not arise from synovial membrane, but from unknown multipotent stem cells. These can differentiate into mesenchymal and epithelial structures and lack synovial differentiation.

On immunohistochemistry, EMA, cytokeratin AE1/AE2, and E-cadherin in combination CD-34 negativity are useful markers for the diagnosis of synovial sarcoma. BCL-2 and MIC-2 (LD-99) are usually positive in synovial sarcoma.

Triple sign occurs due mixture of solid cellular elements, necrosis or hemorrhage and fibrotic or calcified lesions with fluid levels and septa creating the bowel of grapes sign. The triple sign is seen in 35%–57% of synovial sarcoma. The triple sign can also be seen in other soft tissue tumors, and hence, it is not a specific sign of synovial sarcoma.

Synovial sarcoma show translocation fusion of two genes (SYT) on the chromosome 19q11 and SSX1, SSX2, or SXX4 located on chromosome Xp11 break point. Monophasic tumors express either SYT-SSX1 or SYT-SSX2 genetic rearrangement. Biphasic tumors express SYT-SSX1 fusion proteins and have a higher proliferation rate with poor outcome.[5]

The treatment of choice for synovial sarcoma is a wide local excision with negative surgical margin to minimize the chance of recurrence. Radiotherapy is useful in local control of disease in cases of residual tumor. Adjuvant chemotherapy is useful in disease control and consists of regimes combining cyclophosphamide or ifosfamide (alkylating agents) and anthracyclines.

There is a high rate of local recurrence (30%–50%) and metastatic disease in synovial sarcoma. Metastasis occurs in 2–5 years of initial treatment. The 5-year survival rate is 36% to 76% for intermediate to high-grade synovial sarcoma.

Positive surgical margins, invasiveness, metastasis, poor differentiation, and high histological grades are indicative of advance prognosis in synovial sarcoma. Size <5 cm, distal extremity location, age <15 years, monophasic synovial sarcoma, and SYT-SSX2 gene fusion have better prognostic outcomes.[5]

The differential diagnosis includes desmoid tumor, neurofibroma, neurilemmoma and fibroma among benign tumors and rhabdomyosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, mesenchymal chondrosarcoma and metastasis for malignant tumors.[4]

Conclusion

Primary SSAW is a rare extra-articular tumor site. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis of the anterior abdominal wall masses. MRI is useful in detecting extension, multilobulation, planning treatment, and tumor response to chemotherapy.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Saif AH. Primary synovial sarcoma of the abdominal wall: A case report and review of the literature. J Family Community Med 2008; 15: 123-5

- de Haas RJ, Bonenkamp JJ, Flucke UE, de Rooy JW. Synovial sarcoma of the abdominal wall: Imaging findings and review of the literature. J Radiol Case Rep 2015; 9: 24-30

- Kritsaneepaiboon S, Sangkhathat S, Mitarnun W. Primary synovial sarcoma of the abdominal wall: A case report and literature review. J Radiol Case Rep 2015; 9: 47-52

- Kishino T, Morii T, Mochizuki K, Sudo E, Hirano K, Okazaki M. et al. Unusual sonographic appearance of synovial sarcoma of the anterior abdominal wall. J Clin Ultrasound 2009; 37: 233-5

- Karkera PJ, Kothari PR, Sandlas G. Synovial sarcoma of the abdominal wall: An unusual presentation. Clin Cancer Investig J 2013; 2: 53-6

Address for correspondence

Publication History

Received: 30 June 2018

Accepted: 12 September 2018

Article published online:

23 May 2021

© 2020. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

| Figure 1: Ultrasound of the anterior abdominal wall with linear probe showing well-defned solid hypoechoic mass with lobulated outlines in the right iliac fossa in subcutaneous plane (a) causing extrinsic compression and posterior displacement of abdominal wall muscles (b)

| Figure 2: Computed axial tomography of abdomen - plain (a) and contrast (b) showing well-definedsolid mass with lobulated outlines in the right iliac fossa and hypogastric region in subcutaneous plane causing extrinsic compression and posterior displacement of abdominal wall muscles appearing slightly hypodense on plain study (a) showing heterogeneous enhancement in contrast (b)

| Figure 3: Magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen - axial T1 (a), axial T2 (b-d) showing well-definedsolid mass with lobulated outlines in the right iliac fossa and hypogastric region in subcutaneous plane causing extrinsic compression and posterior displacement of abdominal wall muscles appearing slightly hyperintense on the T1-weighted image and hyperintense on T2-weighted image

| Figure 4: Magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen - sagittal T2 (a), coronal T2 (b) showing well-definedsolid mass with lobulated outlines in the right iliac fossa and hypogastric region in subcutaneous plane causing extrinsic compression and posterior displacement of abdominal wall muscles appearing hyperintense on T2-weighted image

| Figure 5: Magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen - axial short tau inversion recovery (a and b) showing well-definedhyperintense solid mass with lobulated outlines in the right iliac fossa and hypogastric region in subcutaneous plane causing extrinsic compression and posterior displacement of the abdominal wall muscles

| Figure 6: Magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen - axial diffusion-weighted imaging (a), apparent diffusion coefficien (b) showing restricted diffusion on diffusion-weighted imaging with low apparent diffusion coefficient value

References

- Saif AH. Primary synovial sarcoma of the abdominal wall: A case report and review of the literature. J Family Community Med 2008; 15: 123-5

- de Haas RJ, Bonenkamp JJ, Flucke UE, de Rooy JW. Synovial sarcoma of the abdominal wall: Imaging findings and review of the literature. J Radiol Case Rep 2015; 9: 24-30

- Kritsaneepaiboon S, Sangkhathat S, Mitarnun W. Primary synovial sarcoma of the abdominal wall: A case report and literature review. J Radiol Case Rep 2015; 9: 47-52

- Kishino T, Morii T, Mochizuki K, Sudo E, Hirano K, Okazaki M. et al. Unusual sonographic appearance of synovial sarcoma of the anterior abdominal wall. J Clin Ultrasound 2009; 37: 233-5

- Karkera PJ, Kothari PR, Sandlas G. Synovial sarcoma of the abdominal wall: An unusual presentation. Clin Cancer Investig J 2013; 2: 53-6

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share