Squamous Cell Carcinoma Lung with Skeletal Muscle Involvement: A 8 year Study of a Tertiary Care Hospital in Kashmir

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2017; 38(04): 456-460

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/ijmpo.ijmpo_169_16

Abstract

Aims: Lung cancer is the mostcommon malignancy throughout the world. Nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the mostcommon type, and squamous cell type is mostcommon in India. Mostly, patients present with chest-related symptoms and signs. Isolated skeletal muscle metastasis (ISMM) is rarely seen. The aim was to see muscle metastasis and its prognosis. Materials and Methods: We are presenting our data of 8 years about thiscommon malignancy with relation to muscle metastasis, either alone or with other system metastasis. Results: Muscle metastasis is seen 1.5% of patients, with male: female of 8:1. Overall median survival was 15 months and progression-free survival was 12 months. Conclusion: One peculiarity seen was ISMM with no pulmonary system and severe paraneoplastic hypercalcemia. Local therapy may be having an impact on overall survival in metachronous muscle involvement.

Keywords

Cytokeratin - isolated skeletal muscle metastasis - nonsmall cell lung carcinoma - overall survival - parathyroid hormone-related peptide - progression-free survival - superior vena cava - thyroid transcription factorPublication History

Article published online:

04 July 2021

© 2017. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used forcommercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Aims:

Lung cancer is the most common malignancy throughout the world. Nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common type, and squamous cell type is most common in India. Mostly, patients present with chest-related symptoms and signs. Isolated skeletal muscle metastasis (ISMM) is rarely seen. The aim was to see muscle metastasis and its prognosis.

Materials and Methods:

We are presenting our data of 8 years about this common malignancy with relation to muscle metastasis, either alone or with other system metastasis.

Results:

Muscle metastasis is seen 1.5% of patients, with male: female of 8:1. Overall median survival was 15 months and progression-free survival was 12 months.

Conclusion:

One peculiarity seen was ISMM with no pulmonary system and severe paraneoplastic hypercalcemia. Local therapy may be having an impact on overall survival in metachronous muscle involvement.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the most common malignancy throughout world, and nonsmall cell histology always outnumbers the small-cell type. Lung cancer has diverse clinical presentations, and chest complaints are the most common. Lung cancer metastise to every organ in the body, but in isolation, rarely involve skeletal muscles. In one retrospective series, the prevalence of isolated skeletal muscle metastasis (SMM) was seen in 0.16%–6%.[1] In a study reported in literature, pain was the most frequent symptom (83%), mass was palpable in 78% of cases, and the diagnosis was obtained by either fine needle/surgical biopsy or wide excision. The 5-year survival time was 11.5% with a median survival of 6 months.[2]

Materials and Methods

A study was conducted in our institute over a period of 8 years. Clinical characteristics of lung cancer were noted down, and types of lung cancer were segregated. Nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC) having muscle metastasis either singly or with multisystem metastasis was taken for study. Patients who had no muscle metastasis were not enrolled for further study. Clinical profile, laboratory, and imaging profile were noted down, and outcome with chemotherapy and other modalities of treatment were recorded. At the end, overall survival was recorded.

Observation and Results

A cancer registry is maintained in our institute for last 15 years, and oncological setup is present over last three decades. We registered 26,660 cancer patients in last 8 years. Out of this data, 4800 (18%) patients had cancer of esophagus & stomach, and 3068 (11.5%) patients had lung cancer. In our registry, upper gastrointestinal tract cancer was rank one tumor followed by lung cancer. Lung cancer was further segregated into common two types as small cell and nonsmall cell variant. Small cell carcinoma lung comprised 460 (15%) patients, and nonsmall cell lung carcinoma comprised 2608 (85%) patients. On morphological and immunohistochemistry, squamous cell carcinoma comprised 1227 (40%) patients, adenocarcinoma of lung comprised 920 (30%) patients, large cell carcinoma 150 (5%) patients, and nonsmall cell carcinoma lung not otherwise specified 306 (10%) patients.

Further study was concentrated on squamous cell carcinoma patients having SMM either singly or with multisystem metastasis. All other patients having either resectable disease or nonmuscle metastatic disease were excluded. All patients underwent imaging of chest and referable sites, along with bone scan, laboratory parameters, and muscle biopsy of involved muscle site. Out of 1227 patients, 18 (1.5%) patients had muscle metastasis. Out of this, ten patients had multiple site metastases along with muscle metastasis and eight patients had only muscle metastasis.

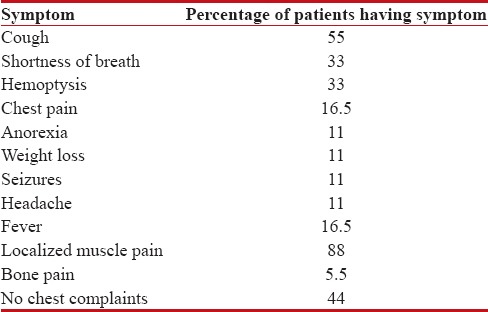

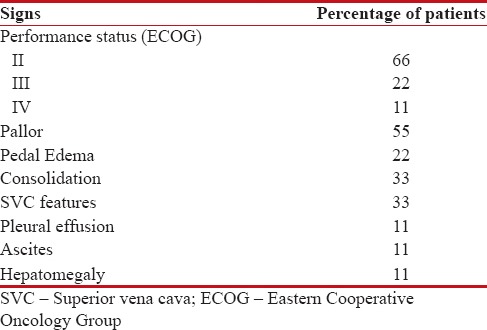

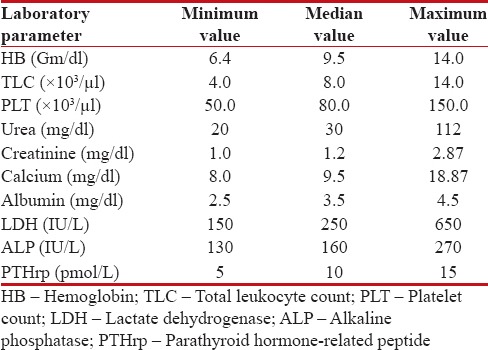

Males were 16 and females were 2, with male: female of 8:1. All patients were smokers, and all were rural dwellers. The clinical features of these patients are depicted in Tables Tables11 and and2.2. The median age of presentation was 48.5 years, with youngest patient of 35 years and oldest patient of 85 years. Among this cohort, the most common symptom was isolated muscle pain followed by cough. The most common sign was pallor followed by SVC syndrome features. In laboratory parameters, anemia was peculiar, renal failure was seen in three patients, which was because of hypercalcemia [Table 3]. Severe hypercalcemia was seen in one patient who required immediate hemodialysis, and this was associated with high parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) level in serum.

Table 1

Symptomatology of presentation

|

Table 2

Clinical signs of patients

|

Table 3

Laboratory parameters

|

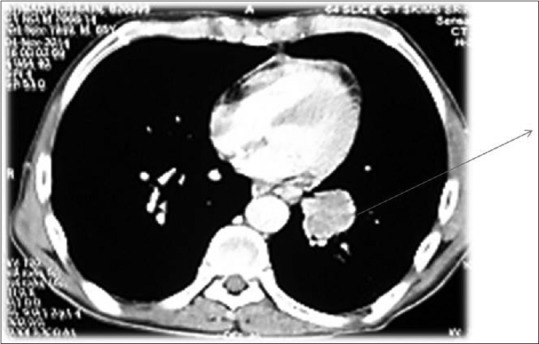

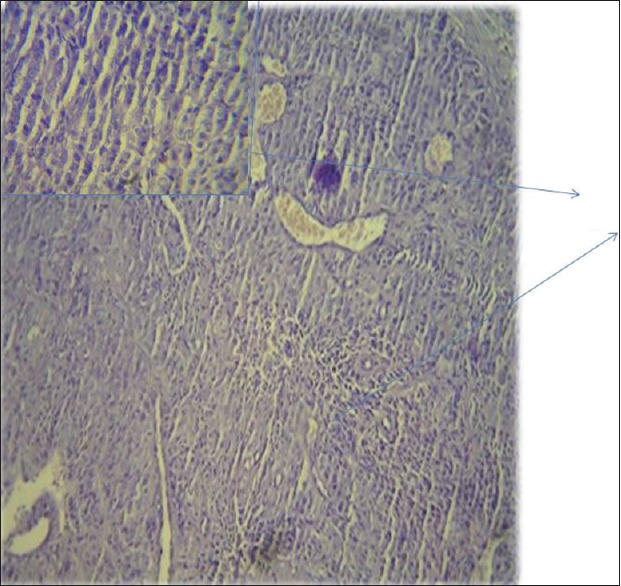

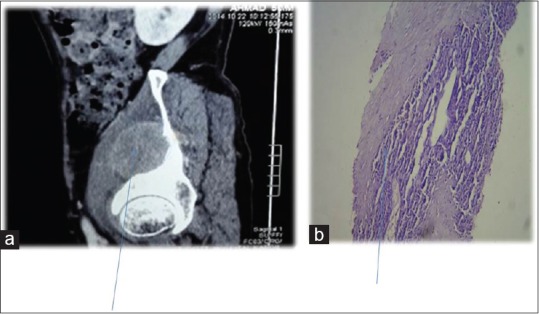

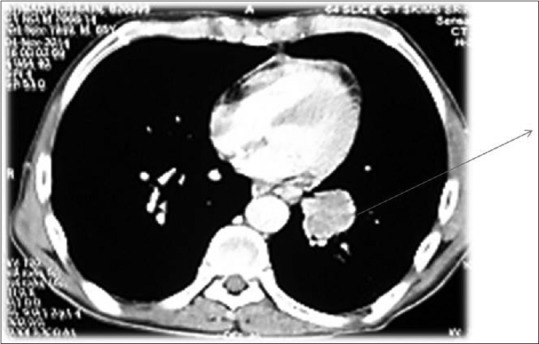

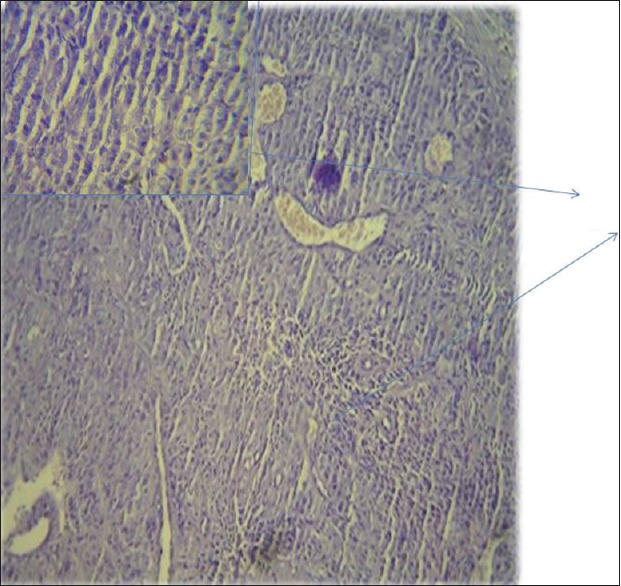

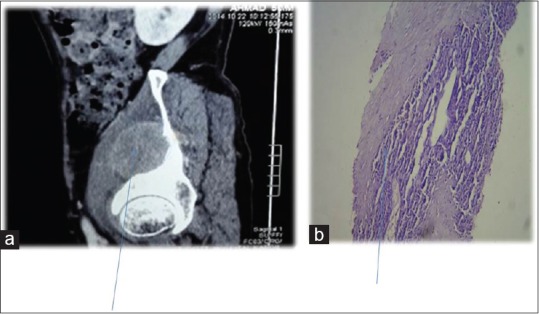

Further evaluation was carried out with imaging of chest and abdomen, along with imaging of referable sites. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) chest and abdomen was carried out in all patients, revealing right hilar mass in 66% of patients, left hilar mass in 22%-of patients, and 12%-had right peripheral lung mass. Superior vena cava (SVC) partial or complete occlusion was seen in 33%; right-sided plural effusion, ascites, and liver metastasis was seen in 11%-each [Figures [Figures11 and and2].2]. Bronchoscopy revealed intrabronchial pathology and clinched the diagnosis in 88% of patients; rest of patients needed computed tomography (CT)-guided biopsy of lung for getting histological diagnosis. Lung biopsy was positive for napsin, cytokeratin (CK) 5/6, and negative for synaptophysin and thyroid transcription factor 1 [Figure 3]. Bone scan was positive in two patients with one uptake in iliac bone and other in Tibia [Figure 4 of X-ray Tibia]. CECT of muscle metastasis sites was done and biopsy was carried out in each patient [Figure 5]. Distribution of metastasis was unique, 66%-patients had pelvic skeletal muscle involvement, 22%-had thigh muscle, and 11%-had lower paraspinal muscle metastasis.

| Figure 1:Contrast-enhanced computed tomography chest showing left hilar mass

| Figure 2:Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showing (a) huge lung mass with necrosis (b) multiple liver metastases

| Figure 3:Histopathology showing squamous cell carcinoma of lung

| Figure 4:Bone metastases in Tibia with sclerosis around lytic lesion

| Figure 5:Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showing (a) Iliacus muscle involvement (b) biopsy of same muscle revealing squamous cell carcinoma metastases

Finally, diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma lung with muscle metastases was established. In our research, 44%-patients had no symptoms referable to chest; they presented with pain in the region of muscle metastases. Most of our patients had contralateral lung metastases; with 16.5%-patients had distant metastases to liver, bone, and brain. Hypercalcemia was seen in 16.5%-patients, all such patients had no bone metastases and was associated with rise of PTHrP, a paraneoplastic manifestation.

Finally, these patients received palliative chemotherapy with supportive treatment, either hemodialysis, bisphosphonates, brain irradiation, blood transfusions, and paracentesis. Patients were divided into two groups, 50%-received gemcitabine 1 g/m2 on day 1 and 8 with carboplatin AUC 5 as 3 weekly schedule and other group received paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 with cisplatin 80 mg/m2 as 3 weekly schedule. On progression of disease, both groups received second-line chemotherapy as docetaxel 75 mg/m2 with growth factor support. Patients who had performance status III/IV received supportive care only.

In both groups, median number of courses received was 6, with 33%-of patients received <6>

First, progression-free survival (PFS) was 6 months in both arms. Maximum PFS was 15 months in gemcitabine arm and 13 months in paclitaxel arm. Second, median PFS was 6 months, with minimum of 4 months. Overall median PFS was 12 months; with maximum PFS of 21 months. Median overall survival was 15 months, with minimum OS of 4 months and maximum OS of 26 months.

We have observed that median OS in our patients was 15 months with median PFS as 12 months. All patients succumbed to chemo toxicity and disease progression. There was some peculiarity of having paraneoplastic hypercalcemia with muscle metastasis in patients having no pulmonary symptoms. Is there some correlation or it was coincidental finding, only research will reveal that.

Discussion

Skeletal muscles are an uncommon site of hematogenous metastases from epithelial neoplasms. Muscle metastases in cancer are very rare.[3] In spite of having huge muscle mass which comprises around 50%-of total body weight, we see rare occurrence of muscle involvement. It is thought that muscular contractile actions, local pH environment, and accumulation of lactic acid and other metabolites contribute to the rare occurrence of this phenomenon.[1] Since it is very difficult to say about true incidence of muscular metastasis, as most of the patients with metastatic disease remain unevaluated toward end of life but still an autopsy series suggests that its incidence could be as low as 0.8%.[4]

Most studies and sporadic reports suggested lung cancer as most common cause of muscle metastases. Many other tumors such as kidney, stomach, pancreas, thyroid gland, breast, and ovary, prostate, and bladder cancers have also been sporadically described in association with intramuscular metastases.[5,6,7,8,9]

Solitary muscle metastasis has been reported in lung cancer by Di Giorgio et al. who reported study of 3000 patients treated for lung cancer, described only three cases showing SMM.[3] Tuoheti et al. found that only 4 (0.16%) out of 2557 patients with lung cancer developed metastasis to the skeletal muscle.[1]

In our study, we also documented the prevalence of skeletal muscle involvement in 1.5% of patients. Males outnumber females because lung cancer is common in males in our part of the world. Most frequent muscle involvement is seen in the thigh, iliopsoas, and paraspinous muscle.[4] In our patient cohort, distribution of metastasis was unique, 66%-patients had pelvic skeletal muscle involvement, 22%-had thigh muscle, and 11%-had lower paraspinal muscle metastasis. A unique thing observed was paraneoplastic hypercalcemia in isolated muscle metastases, even though it was seen in only 16.5%-of patients. In our study, the most common symptom was involved site muscle pain (88%) which is consistent with the study conducted by Pop et al.[2]

According to Prior,[10] the first description of muscle metastasis was reported by Wittich in 1854, and Willis was the first to report a muscle metastasis of lung origin. Despite being highly vascular, the exact incidence is not much known. Subclinical metastasis may indeed be more common than generally thought. One large autopsy study of 5298 people found that 6%-involved SMM of the chest or abdominal wall.[11]

Nowadays, an autopsy on all cancer-related deaths is not performed routinely. An important help is the 18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography - scan mostly for detecting subclinical metastasis.[12,13] Since this imaging procedure was introduced into practice in 2004, single SMM has rarely been seen. Certainly, there are several limitations to muscle enhancement in positron emission tomography scan, so in this study, only the patients with CT scan confirmation and a histologic sample of one metastatic deposit was taken as an absolute metastatic deposit. Almost 1/3 of metastases in this study were discovered before the lung cancer. The most common appearance (83%) of the lesions on contrast-enhanced helical CT is that of a rim-enhancing mass with central hypoattenuation.[14]

There are several theories to explain muscle resistance of metastatic disease. The most important hypotheses are mechanical (muscle contraction, high tissue pressure,[15] and extremely variable blood flow),[16] metabolic (pH, lactic acid production[17] and toxic-free radical oxygen)[15] or immunologic (cellular and humoral immunity and hypersensitivity reaction).[18] None of them in isolation can explain the full mechanism, but a combination of them could.

In our study, median OS was 15 months and PFS was 12 months, with one lived up to 26 months. Since all these patients had synchronous metastatic disease, no patient survived for 5 years. Our OS was better in isolated muscle metastasis than in multiple site metastases. As per the study conducted by Pop et al.,[2] the 5-year survival time was 11.5%-with a median survival of 6 months. Almost all types of nonsmall cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) can metastasize in the muscle with no particular preferences. The presence of SMM suggests an aggressive disease. Selection of patients for a local treatment is an important factor that determines survival, which is possible in metachronous setting or synchronous single site muscle metastases.

Conclusion

Carcinoma lung is always an aggressive disease to handle, when in metastatic stage, curative treatment is not possible. Involvement of muscle is very rarely seen, and if present, tells about aggressive disease. If there is isolated muscle involvement in metachronous setting, one can look for longer survivals with good local treatment. There is also scope for research as why there are high paraneoplastic manifestations in isolated muscle involvements in lung cancer?

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tuoheti Y, Okada K, Osanai T, Nishida J, Ehara S, Hashimoto M, et al. Skeletal muscle metastases of carcinoma: A clinicopathological study of 12 cases. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2004;34:210-4.

- Pop D, Nadeemy AS, Venissac N, Guiraudet P, Otto J, Poudenx M,et al. Skeletal muscle metastasis from non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2009;4:1236-41.

- Di Giorgio A, Sammartino P, Cardini CL, Al Mansour M, Accarpio F, Sibio S,et al. Lung cancer and skeletal muscle metastases. Ann Thorac Surg 2004;78:709-11.

- Kaira K, Ishizuka T, Yanagitani N, Sunaga N, Tsuchiya T, Hisada T,et al. Forearm muscle metastasis as an initial clinical manifestation of lung cancer. South Med J 2009;102:79-81.

- McKeown PP, Conant P, Auerbach LE. Squamous cell carcinoma of the lung: An unusual metastasis to pectoralis muscle. Ann Thorac Surg 1996;61:1525-6.

- Heyer CM, Rduch GJ, Zgoura P, Stachetzki U, Voigt E, Nicolas V, et al. Metastasis to skeletal muscle from esophageal adenocarcinoma. Scand J Gastroenterol 2005;40:1000-4.

- Belhabib D, Maalej S, Fenniche S, Hassene H, Ammar A, Hantous S, et al. Muscle metastasis of a primary bronchial carcinoma. Tunis Med 2001;79:557-60.

- Menard O, Seigneur J, Lamy P. Muscular metastasis of primary bronchial carcinoma. Rev Pneumol Clin 1990;46:183-6.

- Cheong TH, Wang YT, Poh SC, Thung JL. Carcinoma of the lung with metastases to skeletal muscles. Singapore Med J 1989;30:605-6.

- PRIOR C. Metastatic tumors in striated muscle; review and case report. Riv Anat Patol Oncol 1953;6:543-60.

- Picken JW. Use and limitations of autopsy data. In: Weiss L, editor. Fundamental Aspects of Metastasis. Amsterdam: North-Holland; 1976. p. 377-84.

- Heffernan E, Fennelly D, Collins CD. Multiple metastases to skeletal muscle from carcinoma of the esophagus detected by FDG PET-CT imaging. Clin Nucl Med 2006;31:810-1.

- Liu Y, Ghesani N, Mirani N, Zuckier LS. PET-CT demonstration of extensive muscle metastases from breast cancer. Clin Nucl Med 2006;31:266-8.

- Sridhar KS, Rao RK, Kunhardt B. Skeletal muscle metastases from lung cancer. Cancer 1987;59:1530-4.

- ;Toussirot E, Lafforgue P, Tonolli I, Acquaviva PC. Disclosing muscular metastases. Their peculiarities apropos of 3 cases. Rev Rhum Ed Fr 1993;60:167-71.

- Weiss L. Biomechanical destruction of cancer cells in skeletal muscle: A rate-regulator for hematogenous metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis 1989;7:483-91.

- Seely S. Possible reasons for the high resistance of muscle to cancer. Med Hypotheses 1980;6:133-7.

- Zhang P, Meng X, Xia L, Xie P, Sun X, Gao Y,et al. Non-small cell lung cancer with concomitant intramuscular myxoma of the right psoas mimicking intramuscular metastasis: A case report and literature review. Oncol Lett 2015;10:3059-63.

| Figure 1:Contrast-enhanced computed tomography chest showing left hilar mass

| Figure 2:Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showing (a) huge lung mass with necrosis (b) multiple liver metastases

| Figure 3:Histopathology showing squamous cell carcinoma of lung

| Figure 4:Bone metastases in Tibia with sclerosis around lytic lesion

| Figure 5:Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showing (a) Iliacus muscle involvement (b) biopsy of same muscle revealing squamous cell carcinoma metastases

References

- Tuoheti Y, Okada K, Osanai T, Nishida J, Ehara S, Hashimoto M, et al. Skeletal muscle metastases of carcinoma: A clinicopathological study of 12 cases. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2004;34:210-4.

- Pop D, Nadeemy AS, Venissac N, Guiraudet P, Otto J, Poudenx M,et al. Skeletal muscle metastasis from non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2009;4:1236-41.

- Di Giorgio A, Sammartino P, Cardini CL, Al Mansour M, Accarpio F, Sibio S,et al. Lung cancer and skeletal muscle metastases. Ann Thorac Surg 2004;78:709-11.

- Kaira K, Ishizuka T, Yanagitani N, Sunaga N, Tsuchiya T, Hisada T,et al. Forearm muscle metastasis as an initial clinical manifestation of lung cancer. South Med J 2009;102:79-81.

- McKeown PP, Conant P, Auerbach LE. Squamous cell carcinoma of the lung: An unusual metastasis to pectoralis muscle. Ann Thorac Surg 1996;61:1525-6.

- Heyer CM, Rduch GJ, Zgoura P, Stachetzki U, Voigt E, Nicolas V, et al. Metastasis to skeletal muscle from esophageal adenocarcinoma. Scand J Gastroenterol 2005;40:1000-4.

- Belhabib D, Maalej S, Fenniche S, Hassene H, Ammar A, Hantous S, et al. Muscle metastasis of a primary bronchial carcinoma. Tunis Med 2001;79:557-60.

- Menard O, Seigneur J, Lamy P. Muscular metastasis of primary bronchial carcinoma. Rev Pneumol Clin 1990;46:183-6.

- Cheong TH, Wang YT, Poh SC, Thung JL. Carcinoma of the lung with metastases to skeletal muscles. Singapore Med J 1989;30:605-6.

- PRIOR C. Metastatic tumors in striated muscle; review and case report. Riv Anat Patol Oncol 1953;6:543-60.

- Picken JW. Use and limitations of autopsy data. In: Weiss L, editor. Fundamental Aspects of Metastasis. Amsterdam: North-Holland; 1976. p. 377-84.

- Heffernan E, Fennelly D, Collins CD. Multiple metastases to skeletal muscle from carcinoma of the esophagus detected by FDG PET-CT imaging. Clin Nucl Med 2006;31:810-1.

- Liu Y, Ghesani N, Mirani N, Zuckier LS. PET-CT demonstration of extensive muscle metastases from breast cancer. Clin Nucl Med 2006;31:266-8.

- Sridhar KS, Rao RK, Kunhardt B. Skeletal muscle metastases from lung cancer. Cancer 1987;59:1530-4.

- ;Toussirot E, Lafforgue P, Tonolli I, Acquaviva PC. Disclosing muscular metastases. Their peculiarities apropos of 3 cases. Rev Rhum Ed Fr 1993;60:167-71.

- Weiss L. Biomechanical destruction of cancer cells in skeletal muscle: A rate-regulator for hematogenous metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis 1989;7:483-91.

- Seely S. Possible reasons for the high resistance of muscle to cancer. Med Hypotheses 1980;6:133-7.

- Zhang P, Meng X, Xia L, Xie P, Sun X, Gao Y,et al. Non-small cell lung cancer with concomitant intramuscular myxoma of the right psoas mimicking intramuscular metastasis: A case report and literature review. Oncol Lett 2015;10:3059-63.

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share