Spectrum of nonhematological pediatric tumors: A clinicopathologic study of 385 cases

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2014; 35(02): 184-186

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/0971-5851.138995

Abstract

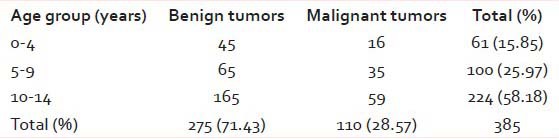

Background: The aim of this study is to understand the epidemiology of tumors in children in our region due to a paucity of studies on the histologic review of the childhood tumors in general and benign tumors in particular. Materials and Methods: The records of all the tumors diagnosed histopathologically in children <14 class="b" xss=removed>Results: A total of 385 tumors were seen in the age range of 1 month-14 years with 231 (60%) in boys and 154 (40%) in girls. Highest number of cases, 224 (58.18%) were in the age group of 10-14 years. Benign tumors comprised 275 (71.43%) cases while the malignant tumors accounted for 110 (28.57%) cases. In benign tumors, vascular tumors were in majority with 68 cases, while in malignant category bone tumors were most common with 36 cases. Conclusions: Although the exact incidence rate cannot be provided by this hospitalbased study, the information is useful in showing patterns of childhood tumors. We included both benign and malignant tumors, while most of the studies in the past have focused mainly on malignant tumors in children

Publication History

Article published online:

19 July 2021

© 2014. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Background:

The aim of this study is to understand the epidemiology of tumors in children in our region due to a paucity of studies on the histologic review of the childhood tumors in general and benign tumors in particular.

Materials and Methods:

The records of all the tumors diagnosed histopathologically in children <14>

Results:

A total of 385 tumors were seen in the age range of 1 month-14 years with 231 (60%) in boys and 154 (40%) in girls. Highest number of cases, 224 (58.18%) were in the age group of 10-14 years. Benign tumors comprised 275 (71.43%) cases while the malignant tumors accounted for 110 (28.57%) cases. In benign tumors, vascular tumors were in majority with 68 cases, while in malignant category bone tumors were most common with 36 cases.

Conclusions:

Although the exact incidence rate cannot be provided by this hospital-based study, the information is useful in showing patterns of childhood tumors. We included both benign and malignant tumors, while most of the studies in the past have focused mainly on malignant tumors in children.

INTRODUCTION

Tumors that occurs in children are as diverse as those in adults and present a number of challenges for the pathologist.[1] Compared with cancers that occur in adults, childhood cancers are rare comprising only 1% of all the cancers.[2] >10% of all deaths in children below 15-year of age are caused by malignant diseases in the developed countries. In the developing world, childhood cancers are yet to be recognized as a major pediatric illness; however, they are fast emerging as a distinct entity to be dealt upon.[3]

The spectrum of pediatric tumors varies considerably and differs from that in adults. Virtually any tumor may be encountered in children, however in general, the principal groups of cancer in children are leukemias, lymphomas, and sarcomas, whereas in adults the chief cancers are carcinomas.[4] The manner of grouping the cancers is also different. For children, the International Classification of Childhood Cancer (ICCC) is used based on morphology of the tumors and is composed of 12 main groups.[5] Benign tumors are more common than the malignant tumors. Most benign tumors are of little concern but on occasion they cause serious disease by virtue of their location or rapid increase in size.[6] Both benign and malignant tumors need a comprehensive evaluation to provide an appropriate diagnosis for designing therapy and predicting prognosis.[7]

The spectrum of malignancies has a great regional variability owing to the environmental and genetic differences.[8] A literature search shows that there is paucity of studies on the histologic review of the childhood tumors in general and benign tumors in particular. In an effort to better understand the epidemiology of tumors in children in our region, a retrospective review of the tumors diagnosed histopathologically was carried out.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study is a retrospective study conducted in the Department of Pathology of a tertiary care hospital, which caters to the patients attending and referred from periphery to the hospital to analyze the spectrum of tumors in children. The records of all the tumors diagnosed histopathologically in children <14>

The tumors were analyzed according to age, sex and histopathological diagnosis. Both benign and malignant tumors diagnosed in children were included, while leukemias were excluded from our study. All tumors were diagnosed on routine hematoxylin and eosin stained sections; special stains and immunohistochemistry was applied wherever necessary. Fine-needle aspiration was done in some cases only. Cytogenetic and molecular studies were not done.

RESULTS

During the 8-year study period, a total of 419 tumors were diagnosed. Of these, the leukemias comprised 34 cases and were excluded from the study. The remaining 385 tumors (including both benign and malignant) diagnosed on histopathology formed the study group.

Clinical profile

The cases included in the present study were in the age range of 1 month-14 years. Highest number of cases was in the age group of 10-14 years [Table 1]. There were 231 (60%) boys and 154 (40%) girls.

Table 1

Age wise distribution of benign and malignant tumors

|

Histopathological diagnosis

Benign tumors

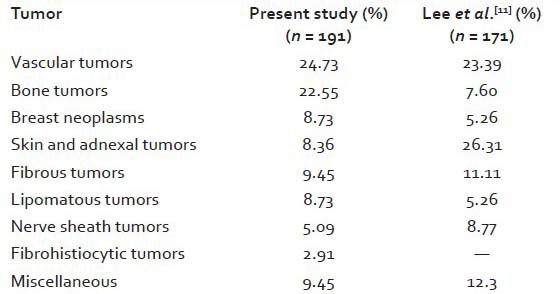

As depicted in Table 2, vascular tumors were the most common including 51 (75%) cases of hemangioma and 17 (25%) cases of lymphangioma. Among the bone tumors, osteochondroma was the most common (48 cases). The others included 6 cases of osteoid osteoma, 5 cases of enchondroma, 2 cases of chondromyxoid fibroma and 1 case of osteoclastoma. Fibroadenoma was seen to occur exclusively in females >10 years of age. There were 4 cases of giant fibroadenoma measuring >10 cm and the morphology of these tumors were usual. Tumors of the skin and its adnexae included 11 cases of pilomatricoma, 10 cases of melanocytic nevi and 1 case each of syringocystadenoma papilliferum and hidradenoma papilliferum. The category of benign fibrous tumors included 10 cases of nasopharyngeal angiofibroma, which was seen to occur exclusively in males >10 years of age, 9 cases of fibroma and 7 cases of fibromatosis. The miscellaneous category included laryngeal papilloma (10 cases), giant cell tumor of tendon sheath (3 cases), mature cystic teratoma (5 cases), pleomorphic adenoma (2 cases), follicular adenoma thyroid, hürthle cell adenoma thyroid, ameloblastoma, tubular adenoma breast, tubular adenoma colon and mucinous cystadenoma ovary (1 case each).

Table 2

Spectrum of benign tumors in children

|

Malignant tumors

These were classified according to the ICCC [Table 3]. Bone tumors were the most common which included 21 cases of Ewing's sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor (ES/PNET), 14 cases of osteosarcoma and 1 case of chondrosarcoma. The category of central nervous system (CNS) tumors included 9 cases of medulloblastoma which were in the posterior fossa and morphologically all were classical. Of the 9 cases of astrocytoma reported in our study, five were low grade and four were pilocytic. Rhabdomyosarcoma formed the largest group in the category of soft tissue sarcoma (8 cases). There were 5 cases of botryoid rhabdomyosarcoma and 3 cases of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. All of them occurred in the head and neck region. Lymphomas included 5 cases of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and 3 cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). The malignant epithelial tumors were comprised by 3 cases of mucoepidermoid carcinoma, 2 cases of adenocarcinoma colon-signet ring cell type and 1 case each of squamous cell carcinoma, papillary carcinoma thyroid and medullary carcinoma thyroid with amyloid. The germ cell tumors were yolk sac tumor, immature teratoma, embryonal carcinoma and mixed type. Of these, three were gonadal and one was extragonadal in location.

Table 3

Spectrum of malignant tumors in children

|

DISCUSSION

Childhood tumors form a highly specific group, mainly embryonal in type and arising in the lymphoreticular tissue, CNS, connective tissue and viscera. Unlike adults, epithelial tumors are rare.[3] The incidence and frequency of childhood tumors has a great geographical variability. In India, although infections and malnutrition are the major factors contributing to morbidity and mortality, malignancies are coming into greater focus because of preventive measures being taken for the former.[9]

Our study attempts to provide a spectrum of tumors in children <14 href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4152636/#ref10" rid="ref10" class=" bibr popnode tag_hotlink tag_tooltip" id="__tag_398581568" role="button" aria-expanded="false" aria-haspopup="true" xss=removed>10] Benign tumors usually have a favorable outcome, but they can cause a lot of concern to the patient and the clinician and rarely may lead to serious complications. This mandates a comprehensive evaluation for appropriate management and a need to study their spectrum in children. Due to a paucity of data on spectrum of benign tumors we compared our findings with that of a study carried out in 1966[11] [Table 4].

Table 4

Comparison of benign tumors

|

Benign tumors

The majority of soft tissue tumors in young adults are benign vascular or fibroblastic proliferations.[12] Majority of breast masses in the pediatric age group are benign, but malignancies do occur.[13] Fibroadenoma is the most frequent breast tumor in adolescent girls.[14] Pilomatricoma, a neoplasm of hair germ matrix origin, is one of the most common cutaneous appendage tumors in patients 20-year of age or younger.[15] Similar to other investigators we noted a predilection of this tumor for the head and neck region and the upper extremities.

Malignant tumors

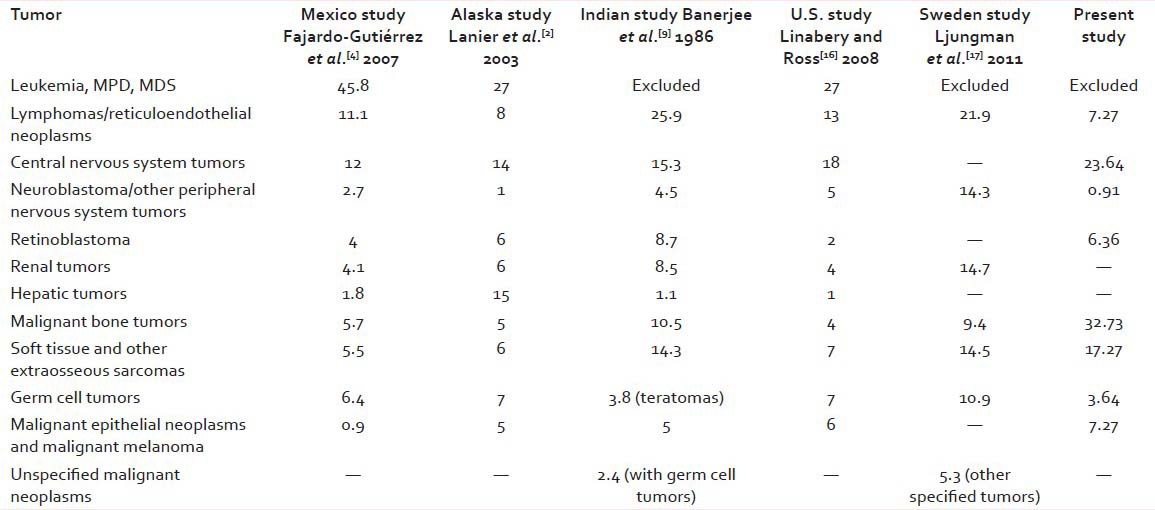

The most frequent childhood cancers arise in the hematopoietic system, nervous tissue, soft tissue, bone and kidney. This is in contrast to adults in whom the skin, lung, breast, prostate and colon are the most common sites of tumors.[6] Childhood cancer comprises a variety of malignancies with incidence varying worldwide by age, sex, ethnicity and geography. Compared with other studies [Table 5] our study has a higher incidence of CNS tumors, malignant bone tumors and soft tissue sarcomas. This could probably be due to regional variation or because of selection bias, our study being a hospital-based study and the number of cases being less compared with the other studies. Diagnosis of bone tumors requires correlation of clinical, radiographic and pathologic findings. The major bone tumors diagnosed were ES/PNET and osteosarcoma, most common in 10-14 years age group which coincides with other series.[9,18] In this study, medulloblastoma and astrocytoma were the most common CNS tumors. The analysis based on data collected by the Manchester Children's Tumor Registry during a 45-year time period (1954-1998) revealed 2511 nonlymphoreticular solid tumors, of which 1055 were CNS tumors, astrocytoma being the most common.[19] Rhabdomyosarcoma comprises the most common single soft tissue sarcoma among children and adolescents and frequently occurs in the head and neck region[20] as was seen in our study. In a large study comprising of 68 cases of soft tissue sarcomas in children in Moscow Region, Russian Federation, rhabdomyosarcoma represented 54.4% of cases.[21] These tumors are unusual in adults. Unique to the pediatric population is infantile fibrosarcoma (1 case), which is a relatively rare tumor and compared to the adult fibrosarcoma has a favorable prognosis.

Table 5

Comparison of malignant tumors with other studies (%)

|

The malignant epithelial tumors are uncommon in the pediatric age group. In the current study, the 2 cases of colorectal carcinoma diagnosed were of signet ring cell type. HL was seen more commonly in our study than NHL and was most frequent in the 10-14 years age group. Banerjee et al.[9] also reported a similar trend. HL is very rare in children younger than 5-year. HL has a bimodal age distribution: In developed countries the first peak occurs in the middle to late 20's and the second peak after the age of 50-year, whereas in the developing countries the early peak occurs before adolescence.[22] Retinoblastoma is the most common primary intraocular malignancy of childhood.[23] Germ cell tumors were mostly gonadal as is frequently seen.[24]

The current study is a single institution based study restricted by a small sample size and this retrospective review cannot serve as a benchmark for reference. Although the cooperative groups’ studies on pediatric neoplasms overcome such a limitation, these are scarce.[17,25] In India, we could not find any large cooperative study on pediatric tumors. This study is an attempt to provide a complete spectrum of childhood tumors diagnosed on histopathology. The study includes both benign and malignant tumors, while most of the previous studies have mainly focused on malignant tumors in children.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Sharma S, Mishra K, Agarwal S, Khanna G. Solid tumors of childhood. Indian J Pediatr 2004;71:501-4.

- Lanier AP, Holck P, Ehrsam Day G, Key C. Childhood cancer among Alaska Natives. Pediatrics 2003;112:e396.

- Kusumakumary P, Jacob R, Jothirmayi R, Nair MK. Profile of pediatric malignancies: A ten year study. Indian Pediatr 2000;37:1234-8.

- Fajardo-Gutiérrez A, Juárez-Ocaña S, González-Miranda G, Palma-Padilla V, Carreón-Cruz R, Ortega-Alvárez MC, et al. Incidence of cancer in children residing in ten jurisdictions of the Mexican Republic: Importance of the Cancer registry (a population-based study). BMC Cancer 2007;7:68.

- Steliarova-Foucher E, Stiller C, Lacour B, Kaatsch P. International Classification of Childhood Cancer, third edition. Cancer 2005;103:1457-67.

- Maitra A. Diseases of infancy and childhood. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC, editors. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 8 th ed. Pennsylvania: Saunders; 2010. p. 447-83.

- Hicks J, Mierau GW. The spectrum of pediatric tumors in infancy, childhood, and adolescence: A comprehensive review with emphasis on special techniques in diagnosis. Ultrastruct Pathol 2005;29:175-202.

- Mamatha HS, Kumari BA, Appaji L, Attili SV, Padma D, Vidya J. Profile of infantile malignancies at tertiary cancer center - A study from south India. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:20026. (Meeting Abstracts).

- Banerjee CK, Walia BN, Pathak IC. Pattern of neoplasms in children. Indian J Pediatr 1986;53:93-7.

- Fischer PR, Ahuka LO, Wood PB, Lucas S. Malignant tumors in children of northeastern Zaire. A comparison of distribution patterns. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1990;29:95-8.

- Lee CK, Ham EK, Kim KY, Chi JG. A histopathologic study on tumors of childhood and adolescence. J KCRA 1966;1:75-80.

- Malone M. Soft tissue tumours in childhood. Histopathology 1993;23:203-16.

- Kaneda HJ, Mack J, Kasales CJ, Schetter S. Pediatric and adolescent breast masses: A review of pathophysiology, imaging, diagnosis, and treatment. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013;200:W204-12.

- Bock K, Duda VF, Hadji P, Ramaswamy A, Schulz-Wendtland R, Klose KJ, et al. Pathologic breast conditions in childhood and adolescence: Evaluation by sonographic diagnosis. J Ultrasound Med 2005;24:1347-54.

- Demircan M, Balik E. Pilomatricoma in children: A prospective study. Pediatr Dermatol 1997;14:430-2.

- Linabery AM, Ross JA. Trends in childhood cancer incidence in the U.S. (1992-2004). Cancer 2008;112:416-32.

- Ljungman G, Jakobson A, Behrendtz M, Ek T, Friberg LG, Hjalmars U, et al. Incidence and survival analyses in children with solid tumours diagnosed in Sweden between 1983 and 2007. Acta Paediatr 2011;100:750-7.

- Eyre R, Feltbower RG, Mubwandarikwa E, Jenkinson HC, Parkes S, Birch JM, et al. Incidence and survival of childhood bone cancer in northern England and the West Midlands, 1981-2002. Br J Cancer 2009;100:188-93.

- McNally RJ, Kelsey AM, Cairns DP, Taylor GM, Eden OB, Birch JM. Temporal increases in the incidence of childhood solid tumors seen in Northwest England (1954-1998) are likely to be real. Cancer 2001;92:1967-76.

- Parham DM, Ellison DA. Rhabdomyosarcomas in adults and children: An update. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2006;130:1454-65.

- Kachanov DY, Dobrenkov KV, Abdullaev RT, Shamanskaya TV, Varfolomeeva SR. Incidence and survival of pediatric soft tissue sarcomas in moscow region, Russian Federation, 2000-2009. Sarcoma 2012;2012:350806.

- Toma P, Granata C, Rossi A, Garaventa A. Multimodality imaging of Hodgkin disease and non-Hodgkin lymphomas in children. Radiographics 2007;27:1335-54.

- Madhavan J, Ganesh A, Roy J, Biswas J, Kumaramanickavel G. The relationship between tumor cell differentiation and age at diagnosis in retinoblastoma. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 2008;45:22-5.

- Ueno T, Tanaka YO, Nagata M, Tsunoda H, Anno I, Ishikawa S, et al. Spectrum of germ cell tumors: From head to toe. Radiographics 2004;24:387-404.

- Gatta G, Capocaccia R, Stiller C, Kaatsch P, Berrino F, Terenziani M, et al. Childhood cancer survival trends in Europe: A EUROCARE Working Group study. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:3742-51.

References

- Sharma S, Mishra K, Agarwal S, Khanna G. Solid tumors of childhood. Indian J Pediatr 2004;71:501-4.

- Lanier AP, Holck P, Ehrsam Day G, Key C. Childhood cancer among Alaska Natives. Pediatrics 2003;112:e396.

- Kusumakumary P, Jacob R, Jothirmayi R, Nair MK. Profile of pediatric malignancies: A ten year study. Indian Pediatr 2000;37:1234-8.

- Fajardo-Gutiérrez A, Juárez-Ocaña S, González-Miranda G, Palma-Padilla V, Carreón-Cruz R, Ortega-Alvárez MC, et al. Incidence of cancer in children residing in ten jurisdictions of the Mexican Republic: Importance of the Cancer registry (a population-based study). BMC Cancer 2007;7:68.

- Steliarova-Foucher E, Stiller C, Lacour B, Kaatsch P. International Classification of Childhood Cancer, third edition. Cancer 2005;103:1457-67.

- Maitra A. Diseases of infancy and childhood. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC, editors. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 8 th ed. Pennsylvania: Saunders; 2010. p. 447-83.

- Hicks J, Mierau GW. The spectrum of pediatric tumors in infancy, childhood, and adolescence: A comprehensive review with emphasis on special techniques in diagnosis. Ultrastruct Pathol 2005;29:175-202.

- Mamatha HS, Kumari BA, Appaji L, Attili SV, Padma D, Vidya J. Profile of infantile malignancies at tertiary cancer center - A study from south India. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:20026. (Meeting Abstracts).

- Banerjee CK, Walia BN, Pathak IC. Pattern of neoplasms in children. Indian J Pediatr 1986;53:93-7.

- Fischer PR, Ahuka LO, Wood PB, Lucas S. Malignant tumors in children of northeastern Zaire. A comparison of distribution patterns. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1990;29:95-8.

- Lee CK, Ham EK, Kim KY, Chi JG. A histopathologic study on tumors of childhood and adolescence. J KCRA 1966;1:75-80.

- Malone M. Soft tissue tumours in childhood. Histopathology 1993;23:203-16.

- Kaneda HJ, Mack J, Kasales CJ, Schetter S. Pediatric and adolescent breast masses: A review of pathophysiology, imaging, diagnosis, and treatment. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013;200:W204-12.

- Bock K, Duda VF, Hadji P, Ramaswamy A, Schulz-Wendtland R, Klose KJ, et al. Pathologic breast conditions in childhood and adolescence: Evaluation by sonographic diagnosis. J Ultrasound Med 2005;24:1347-54.

- Demircan M, Balik E. Pilomatricoma in children: A prospective study. Pediatr Dermatol 1997;14:430-2.

- Linabery AM, Ross JA. Trends in childhood cancer incidence in the U.S. (1992-2004). Cancer 2008;112:416-32.

- Ljungman G, Jakobson A, Behrendtz M, Ek T, Friberg LG, Hjalmars U, et al. Incidence and survival analyses in children with solid tumours diagnosed in Sweden between 1983 and 2007. Acta Paediatr 2011;100:750-7.

- Eyre R, Feltbower RG, Mubwandarikwa E, Jenkinson HC, Parkes S, Birch JM, et al. Incidence and survival of childhood bone cancer in northern England and the West Midlands, 1981-2002. Br J Cancer 2009;100:188-93.

- McNally RJ, Kelsey AM, Cairns DP, Taylor GM, Eden OB, Birch JM. Temporal increases in the incidence of childhood solid tumors seen in Northwest England (1954-1998) are likely to be real. Cancer 2001;92:1967-76.

- Parham DM, Ellison DA. Rhabdomyosarcomas in adults and children: An update. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2006;130:1454-65.

- Kachanov DY, Dobrenkov KV, Abdullaev RT, Shamanskaya TV, Varfolomeeva SR. Incidence and survival of pediatric soft tissue sarcomas in moscow region, Russian Federation, 2000-2009. Sarcoma 2012;2012:350806.

- Toma P, Granata C, Rossi A, Garaventa A. Multimodality imaging of Hodgkin disease and non-Hodgkin lymphomas in children. Radiographics 2007;27:1335-54.

- Madhavan J, Ganesh A, Roy J, Biswas J, Kumaramanickavel G. The relationship between tumor cell differentiation and age at diagnosis in retinoblastoma. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 2008;45:22-5.

- Ueno T, Tanaka YO, Nagata M, Tsunoda H, Anno I, Ishikawa S, et al. Spectrum of germ cell tumors: From head to toe. Radiographics 2004;24:387-404.

- Gatta G, Capocaccia R, Stiller C, Kaatsch P, Berrino F, Terenziani M, et al. Childhood cancer survival trends in Europe: A EUROCARE Working Group study. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:3742-51.

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share