Real-World Evidence Data on Adverse Reactions to Infusion of Thawed Hematopoietic Progenitor Cells: Retrospective Analysis from a Single Center in India

CC BY 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2025; 46(01): 057-063

DOI: 10.1055/s-0044-1788311

Abstract

Introduction Adverse reactions (ARs) occur during infusion of thawed hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) either due to infusion or its contents. There is sparse literature on it in the world and none in India. Therefore, we retrospectively analyzed ARs occurring during and within 1 hour of infusion of thawed HPCs.

Objective This study aimed to evaluate the prevalence of adverse reactions associated with the infusion of cryopreserved hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPC) and to categorize the types of adverse reactions observed in HPC transplant recipients during its infusion.

Materials and Methods This study was done in a tertiary-care center, between 2019 and 2022. Data collected included age, gender, diagnosis, specifications of contents of infusion product (volume of product, volume of dimethyl sulfoxide per kg body weight, total nucleated cell count per microliter, and viability of CD 34+ cells), pretreatment given, and ARs, if any from the procedure records and the hospital information system.

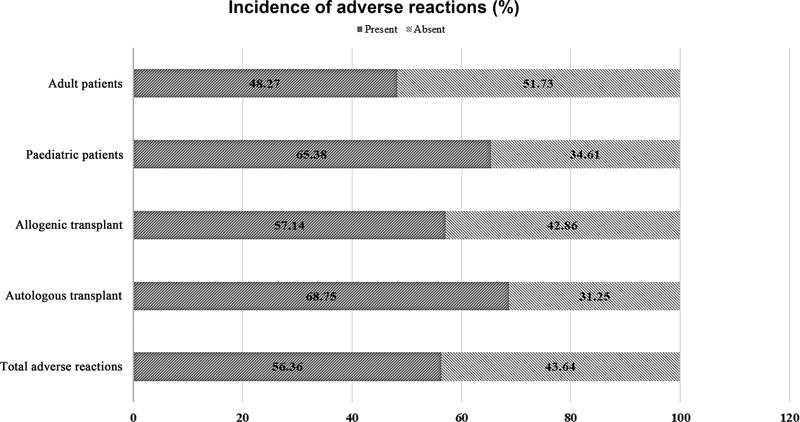

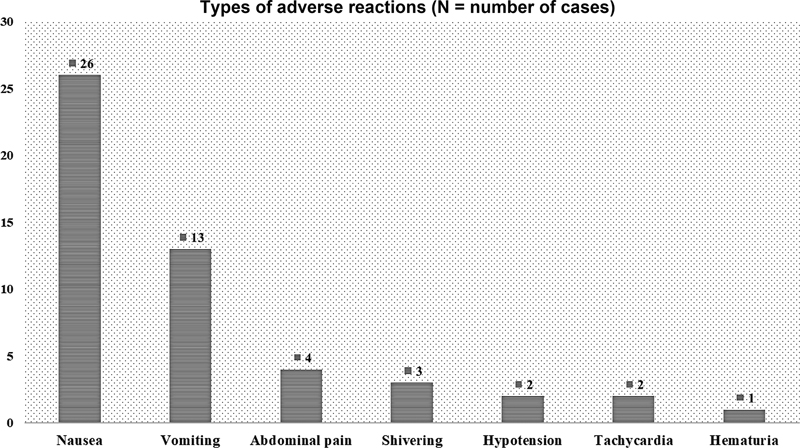

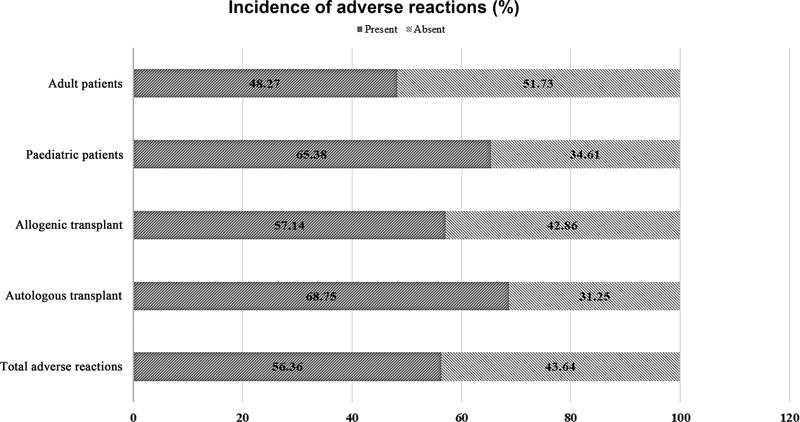

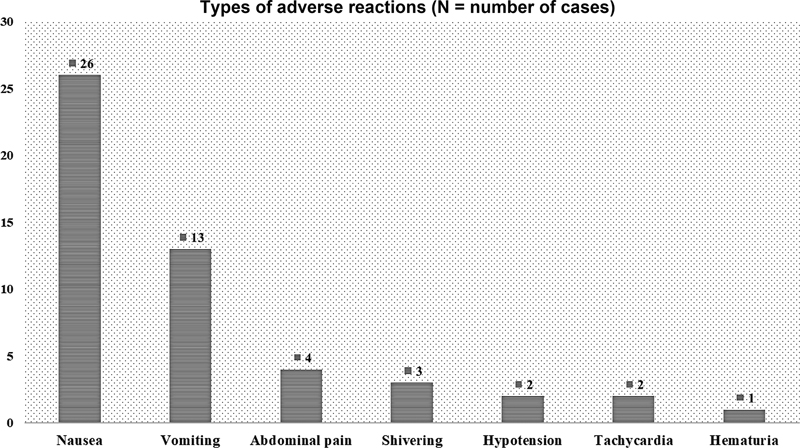

Results The present study included 55 transplant patients, and the commonest diagnosis was Hodgkin lymphoma. All were prophylactically hydrated and premedicated as per institutional protocol. AR was seen in 56.36%, (n = 31); the commonest type of ARs was nausea (n = 26) followed by vomiting (n = 13), abdominal pain (n = 4), shivering (n = 3), transient tachycardia (n = 2), transient hypotension (n = 2), and hematuria (n = 1). All ARs were managed clinically by giving symptomatic treatment. No patients required intensive care, and there were no deaths or aborted procedures. Characteristics of infusion products had no significant correlation to ARs.

Conclusions To the best of the author's knowledge, this is the first such study from India. We report an overall incidence of ARs of 56.36%, which is similar to the previously published data on ARs during thawed HPC infusions. AR is a common occurrence and can be managed medically and symptomatically.

Note

The manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors and the requirements for authorship have been met. Each author believes that the manuscript represents honest work.

Author's Contributions

A.K.T. conceptualized and designed the study protocol, screened eligible studies previously published and analyzed the data. G.A. and S. Pabbi contributed to writing the report, analyzing data, and interpreting the results. S. Pawar, S. Golia, and S. Gupta contributed to extracting data from the procedure sheet and HIS, writing the report, and updating the reference lists. G.R. provided technical support during the conduct of the study. N.S. and S.Y. contributed to manuscript editing and review. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Patient Consent

Informed consent was obtained from each patient before commencing treatment. Patient identifiers were removed and complete confidentiality was maintained. There was no study-specific consent since anonymised data was used for this observational analysis. Institutional review board (IRB) gave a waiver for study-specific consent.

Publication History

Article published online:

22 July 2024

© 2024. The Author(s). This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, permitting unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction so long as the original work is properly cited. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

- Effect of restrictive versus liberal red cell transfusion strategies on haemostasis: systematic review and meta-analysisMichael J. R. Desborough, Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 2017

- Updates in Red Blood Cell and Platelet Transfusions in Preterm NeonatesEnrico Lopriore, American Journal of Perinatology, 2019

- Updates in Red Blood Cell and Platelet Transfusions in Preterm NeonatesEnrico Lopriore, American Journal of Perinatology, 2019

- Influence of Residual Platelet Count on Routine Coagulation, Factor VIII, and Factor IX Testing in Postfreeze-Thaw SamplesGiuseppe Lippi, Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis, 2013

- Influence of Residual Platelet Count on Routine Coagulation, Factor VIII, and Factor IX Testing in Postfreeze-Thaw SamplesGiuseppe Lippi, Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis, 2013

- Application of low molecular heparin to hemoperfusion for acute poisoningSHAO Shao-kun 1, Featured Articles on COVID from Shanghai Journal of Preventive Medicine

- 973-P: By How Much Does Red Blood Cell Status Affect the Accuracy of HbA1c?ANDREAS KARWATH, Diabetes, 2022

- Nucleated Red Blood Cells and Artifactual HypoglycemiaChamel I Macaron, Diabetes Care, 1981

- Tolbutamide-induced hemolytic anemia.P Malacarne, Diabetes, 1977

- Evaluation of GHb Assays in France by National Quality Control SurveysPhilippe Gillery, Diabetes Care, 1998

Abstract

Introduction Adverse reactions (ARs) occur during infusion of thawed hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) either due to infusion or its contents. There is sparse literature on it in the world and none in India. Therefore, we retrospectively analyzed ARs occurring during and within 1 hour of infusion of thawed HPCs.

Objective This study aimed to evaluate the prevalence of adverse reactions associated with the infusion of cryopreserved hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPC) and to categorize the types of adverse reactions observed in HPC transplant recipients during its infusion.

Materials and Methods This study was done in a tertiary-care center, between 2019 and 2022. Data collected included age, gender, diagnosis, specifications of contents of infusion product (volume of product, volume of dimethyl sulfoxide per kg body weight, total nucleated cell count per microliter, and viability of CD 34+ cells), pretreatment given, and ARs, if any from the procedure records and the hospital information system.

Results The present study included 55 transplant patients, and the commonest diagnosis was Hodgkin lymphoma. All were prophylactically hydrated and premedicated as per institutional protocol. AR was seen in 56.36%, (n = 31); the commonest type of ARs was nausea (n = 26) followed by vomiting (n = 13), abdominal pain (n = 4), shivering (n = 3), transient tachycardia (n = 2), transient hypotension (n = 2), and hematuria (n = 1). All ARs were managed clinically by giving symptomatic treatment. No patients required intensive care, and there were no deaths or aborted procedures. Characteristics of infusion products had no significant correlation to ARs.

Conclusions To the best of the author's knowledge, this is the first such study from India. We report an overall incidence of ARs of 56.36%, which is similar to the previously published data on ARs during thawed HPC infusions. AR is a common occurrence and can be managed medically and symptomatically.

Keywords

adverse reactions - infusion - transplant - hematopoietic progenitor cellIntroduction

Hematopoietic progenitor cell (HPC) transplant is done for various indications, both benign and malignant; benign disorders such as thalassemia major, sickle cell anemia, aplastic anemia, and malignant disorders such as acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes, myeloproliferative disorders, acute lymphocytic leukemia, chronic myeloid leukemia, multiple myeloma, and lymphomas.

There are three major forms of HPC transplants performed clinically: (1) autologous transplantation, in which the patient serves as a self-donor; (2) allogeneic transplantation, from another person, and (3) cord blood transplant.[1] In autologous transplantation, the reinfusion of the patient's HPCs allows for the recovery of the marrow following high-dose myeloablative chemotherapy and is, hence, also known as bone marrow rescue.[2]

While cord HPC is infrequent, the commonest transplant in clinical settings is allogeneic HPC transplantation, where the healthy donor provides HPC either from bone marrow (HPC-M) or from peripheral blood through an apheresis procedure (HPC-A).[2] HPC-A has almost replaced HPC-M because of the ease and safety of collection and quicker recovery of granulocytes and platelets from the apheresis procedure compared with bone marrow collection.[1]

Harvested HPC-A can be stored at 4°C for up to 2 days in certain cases, such as multiple myeloma, where patient conditioning is quicker.[3] It must be cryopreserved in cases such as lymphoma, where patient conditioning takes 6 to 7 days or the HPC product must be shipped to a different state or country. Advancement in HPC processing over the years has led to the ability to cryopreserve cells for long-term storage, wherein stem cells can be collected in advance, cryopreserved, and then infused after the administration of myeloablative doses of chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy in the recipients.[4]

Once the patient is conditioned, the HPC is infused to reconstitute the hematopoietic system. Such infusion of HPCs is generally a safe procedure, but these infusions have the potential to cause adverse reactions (ARs). These range from mild reactions such as nausea, vomiting, fever, flushing, chills, and cough to severe reactions affecting cardiovascular, respiratory, and neurological systems.[5] Mild ARs are more common than severe or life-threatening ARs.[5]

ARs due to the infusion of thawed HPCs are not well-documented globally, and there is a lack of literature on this in India. Therefore, we observed and analyzed ARs occurring within 1 hour of infusion in transplant recipients in our retrospective cohort of 4 years.

Materials and Methods

Settings

This observational analytical study was conducted between 2019 and 2022 at a tertiary care hospital in India. The study population included all patients who were transfused thawed HPC during the study period.

Collection and Cryopreservation

HPCs were collected through an apheresis (HPC-A) procedure using an automated cell separator machine (Com.Tec [Fresenius Kabi AG, Bad Homburg, Germany]) from donors (allogeneic transplant) or patients (autologous transplants). The donors/patients were mobilized using a granulocyte-colony stimulating factor with/without CXCR4 inhibitor (Plerixafor). After the target CD34 positive cell dose was achieved (4–6 million cells/kg body weight for allogeneic transplant and 2–4 million cells/kg body weight for autologous transplant), the collected HPC-A product was transported to an outside National Accreditation Board for Testing and Calibration Laboratories (NABL)-accredited Good Laboratory Practices (GLP)-certified cellular-therapy laboratory for cryopreservation. The HPC-A product was centrifuged, and excess plasma was expressed off.

The product was then transferred into freezing bags, and cryoprotectant solution (100%, dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) and sedimentation agent (6%, hydroxyethyl starch [HES]) were added according to the product volume. The final concentration of DMSO was 5%.[6] [7] A small aliquot (1 mL) was separated to serve as a control for the cryopreservation process. The final HPC-A product was frozen using a controlled rate freezer and then cryopreserved at less than −196°C in a vapor-phase liquid nitrogen storage freezer.

The viability of the infusion product was done twice, prefreezing and preinfusion by flow cytometry using 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD). These tests were done at the same laboratory that performed the cryopreservation (NABL-accredited GLP certified). The final CD34 infusion dose was based on both postthaw viability and flow cytometry CD34 counts.

Thawing and Infusion

On the day of the transplant, cryopreserved HPC product was transported to the transplantation center in a temperature-monitored liquid-nitrogen cryoshipper (MVE Cryoshipper, MVE Biological Solutions, LLC, United States). The cryopreserved HPC product was thawed bedside to 37°C using a dry-plasma thawer (Barkey Plasmatherm V, Barkey GmbH & Co. KG, Germany). The process was done under sterile conditions by a transfusion medicine specialist, in the presence of a transplant physician.

The HPC infusion was performed in a positive pressure room fitted with a high-efficiency particulate air filter. All the patients were prophylactically hydrated (10–15 mL/kg body weight, up to 1 L) and premedicated with an antihistaminic (injection Pheniramine maleate 2 mL stat) and an antipyretic (Paracetamol infusion 10 mg/kg body weight, maximum dose of 1 g) as per institutional protocol, 30 minutes before the start of infusion.

The infusion was initiated through a peripherally inserted central catheter (line) in all patients immediately after thawing at the rate of 20 mL/min. The rate of infusion was increased up to 50 mL/min if the patient had no AR in the first 10 minutes. The patients were monitored for vital signs including blood pressure, pulse, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation during and after the infusion.

Adverse Reaction Definition/Record

ARs were defined according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events criteria.[8] Vital signs included hypotension (systolic pressure < 90 mm Hg, if previously normotensive or a decrease in systolic pressure of 20 mm Hg), hypertension (> 150/100 mm Hg if previously normotensive or an increase > 20 mm Hg in diastolic blood pressure), bradycardia (heart rate < 60 bpm), tachycardia (heart rate > 100 bpm), arrhythmia, hypoxia (oxygen saturation < 95%), tachypnoea (respiratory rate > 20), fever (temperature > 38°C), and hypothermia (temperature < 35°C).

Vital signs were recorded at the start of infusion and at 15-minute intervals thereafter till 1-hour postinfusion. Any AS occurring during and within 1-hour postinfusion was documented in the procedure sheet. Management was done according to the institutional standard operating procedures.

Postinfusion Protocol

Reverse barrier nursing was practiced according to the institutional protocol. Patient monitoring was done for laboratory parameters at defined frequency (complete blood counts and electrolytes once a day; liver function tests, renal function tests, and blood glucose twice a week; blood culture as and when deemed necessary). Antimicrobial prophylaxis included antibacterial (levofloxacin), antifungal (fluconazole), and antiviral (acyclovir) activities.

Data Collection

Data collected included patient/recipient age (≤18-year-old were considered in the “children” subgroup), gender, diagnosis, details of the infusion product (like volume of infusion product, volume of DMSO per kg body weight, total nucleated cell count (TNCC) per microliter, viability of CD 34+ cells), pretreatment given, and AS, if any. The data were collected from the procedure sheet filled at the time of infusion and from the hospital information system (HIS).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All the patients who underwent infusion of thawed HPCs and filled procedure sheets were included in the study. Any patient with an incompletely filled procedure sheet was excluded from the study.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed, and mean, median, and range were calculated using Microsoft Excel software and SPSS Software version 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, United States); p-values <0>

Ethical Approval

The study has been approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee on 29.03.2023, Reference no: 1513/2023 (Academic). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Results

Demographics and Patient Characteristics

Fifty-five patients were transfused thawed HPC-A during the study period, and all of them were included in the study analysis. There were 32 males and 23 females (M:F was 1.39:1). Twenty-nine were adult patients (52.72%), and twenty-six were children (47.27%). The most common diagnosis for which these patients were undergoing HPC transplant was Hodgkin lymphoma followed by diffuse large B cell lymphoma. All patients were transfused infusion volume on a single day.

Complete patient characteristics are mentioned in [Table 1].

|

Patient characteristics |

n (%) |

|---|---|

|

Gender |

|

|

Female |

32 (58.2%) |

|

Male |

23 (41.8%) |

|

Age group (in years) |

|

|

≤18 |

26 (47.27%) |

|

19–30 |

12 (21.81%) |

|

31–50 |

11 (20%) |

|

>50 |

06 (10.90%) |

|

Diagnosis |

|

|

Hodgkin lymphoma |

16 (29.1%) |

|

Diffuse large B cell lymphoma |

11 (20%) |

|

Rhabdoid tumor |

06 (10.9%) |

|

T cell lymphoma |

03 (5.50%) |

|

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Ewing's sarcoma, thalassemia major |

02 cases each |

|

Germ cell tumor, lymphoma, GI lymphoma, primary CNS lymphoma, neuroblastoma, medulloblastoma, multiple myeloma, osteosarcoma, sickle cell anemia, Wilm's tumor, ALL |

01 case each |

|

Type of transplant |

|

|

Autologous |

49 (89.09%) |

|

Allogeneic |

06 (10.90%) |

|

Characteristics |

Mean ± SD |

Minimum |

Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Total volume transfused (mL) |

334.8 ± 203.1 |

21.5 |

792.0 |

|

Infusion product per kg body weight |

6.1 ± 3.1 |

0.6 |

19.1 |

|

CD 34+ cells per kg body weight |

7.1 ± 6.1 |

1.7 |

39.0 |

|

Volume of DMSO (mL) |

32.4 ± 17.1 |

4.0 |

72.0 |

|

TNCC × 103 / μL |

215.5 ± 123.4 |

9.0 |

469.0 |

|

Viability (%) |

92.4 ± 4.6 |

76.0 |

99.0 |

| | Fig 1Incidence of adverse reactions in different study groups.|

| Fig 2 Types of adverse reactions in the study population.|

Management of Adverse Reactions

All AR were managed clinically, as shown in [Table 3]. No patients required intensive care, and there were no deaths or aborted procedures.

|

Adverse reaction |

Management |

Median time to resolution |

|---|---|---|

|

Nausea, vomiting |

Antiemetic given stat |

16 min |

|

Transient tachycardia, transient hypotension, shivering |

Slowing of infusion rate till the reaction subsided |

28 min |

|

Hematuria |

Double maintenance fluids given till the reaction subsides |

110 min |

|

Abdominal pain |

Antispasmodic given stat |

36 min |

|

S. No. |

Year of publication |

Study |

Concentration of DMSO infused |

Sample size (n) |

Incidence (%) |

Type of adverse reactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1. |

Present study |

5%, |

55 |

56.36%, |

50.98%, (n = 26) nausea 25.49%, (n = 13) vomiting 7.84%, (n = 4) abdominal pain 5.88%, (n = 3) shivering 3.92%, (n = 2) transient tachycardia 3.92%, (n = 2) transient hypotension 1.96%, (n = 1) hematuria |

|

|

2. |

2007 |

Cordoba et al[13] |

5–10%, |

144 |

67.36 |

43.75%, allergic reactions 25%, gastrointestinal symptoms 20.83%, respiratory symptoms 11.81%, cardiovascular symptoms 3.47%, neurological symptoms |

|

3. |

2015 |

Vidula et al[8] |

10%, |

460 |

56.7 |

48%, cardiovascular symptoms 14.3%, respiratory symptoms 4.6%, gastrointestinal symptoms 3.5%, constitutional symptoms 1.1%, neurological symptoms 0.22%, genitourinary symptoms |

|

4. |

2016 |

Truong et al[5] |

10%, |

213 |

55 |

Most common reaction was nausea (42%), followed by vomiting (28%) |

|

5. |

2017 |

Otrock et al[14] |

10%, |

1,269 |

37.8 |

39.4%, facial flushing 38.1%, nausea and/or vomiting 29%, hypoxia requiring oxygen 16.7%, chest tightness 12.1%, cough 8.3%, shortness of breath 7.3%, cardiovascular symptoms |

References

- Simon TL, McCullough J, Snyder EL. et al, eds. Rossi's Principles of Transfusion Medicine. 6th ed.. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2022: 617-623

- Connelly-Smith LS, Linenberger ML. eds. The collection and processing of hematopoietic progenitor cells. In: AABB Technical Manual. 20th ed.. MD: American Association of Blood Banks; 2020: 737-758

- Pamphilon D, Mijovic A. Storage of hemopoietic stem cells. Asian J Transfus Sci 2007; 1 (02) 71-76

- Wingard JR, Gastineau DA, Leather HL. et al, eds. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Handbook for Clinicians, 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: AABB; 2015: 228-231

- Truong TH, Moorjani R, Dewey D, Guilcher GM, Prokopishyn NL, Lewis VA. Adverse reactions during stem cell infusion in children treated with autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2016; 51 (05) 680-686

- Lecchi L, Giovanelli S, Gagliardi B, Pezzali I, Ratti I, Marconi M. An update on methods for cryopreservation and thawing of hemopoietic stem cells. Transfus Apheresis Sci 2016; 54 (03) 324-336

- Bakken AM. Cryopreserving human peripheral blood progenitor cells. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther 2006; 1 (01) 47-54

- Vidula N, Villa M, Helenowski IB. et al. Adverse events during hematopoietic stem cell infusion: analysis of the infusion product. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2015; 15 (11) e157-e162

- Devadas SK, Khairnar M, Hiregoudar SS. et al. Is long term storage of cryopreserved stem cells for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation a worthwhile exercise in developing countries?. Blood Res 2017; 52 (04) 307-310

- Mukhopadhyay A, Gupta P, Basak J. et al. Stem cell transplant: an experience from eastern India. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2012; 33 (04) 203-209

- Jain R, Hans R, Totadri S. et al. Autologous stem cell transplant for high-risk neuroblastoma: achieving cure with low-cost adaptations. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2020; 67 (06) e28273

- Setia RD, Arora S, Handoo A. et al. Outcome of 51 autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplants after uncontrolled-rate freezing (“dump freezing”) using -80°C mechanical freezer. Asian J Transfus Sci 2018; 12 (02) 117-122

- Cordoba R, Arrieta R, Kerguelen A, Hernandez-Navarro F. The occurrence of adverse events during the infusion of autologous peripheral blood stem cells is related to the number of granulocytes in the leukapheresis product. Bone Marrow Transplant 2007; 40 (11) 1063-1067

- Otrock ZK, Sempek DS, Carey S, Grossman BJ. Adverse events of cryopreserved hematopoietic stem cell infusions in adults: a single-center observational study. Transfusion 2017; 57 (06) 1522-1526

- Gokarn A, Tembhare PR, Syed H. et al. Long-term cryopreservation of peripheral blood stem cell harvest using low concentration (4.35%) dimethyl sulfoxide with methyl cellulose and uncontrolled rate freezing at -80 °C: an effective option in resource-limited settings. Transplant Cell Ther 2023; 29 (12) 777.e1-777.e8

- Solves P, Penalver M, Arnau MJ. et al. Adverse events after infusion of cryopreserved and non cryopreserved hematopoietic progenitor cells from different sources. Ann Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018; 1 (01) 1004

-

Martín-Henao GA,

Resano PM,

Villegas JM.

et al.

Adverse reactions during transfusion of thawed haematopoietic progenitor cells from apheresis are closely related to the number of granulocyte cells in the leukapheresis product. Vox Sang 2010; 99 (03) 267-273

Address for correspondence

Aseem K. Tiwari, MDDepartment of Transfusion Medicine, Medanta-The MedicitySector-38, Gurgaon 122001, HaryanaIndiaEmail: draseemtiwari@gmail.comPublication History

Article published online:

22 July 2024© 2024. The Author(s). This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, permitting unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction so long as the original work is properly cited. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, IndiaWe recommend- Effect of restrictive versus liberal red cell transfusion strategies on haemostasis: systematic review and meta-analysisMichael J. R. Desborough, Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 2017

- Updates in Red Blood Cell and Platelet Transfusions in Preterm NeonatesEnrico Lopriore, American Journal of Perinatology, 2019

- Updates in Red Blood Cell and Platelet Transfusions in Preterm NeonatesEnrico Lopriore, American Journal of Perinatology, 2019

- Influence of Residual Platelet Count on Routine Coagulation, Factor VIII, and Factor IX Testing in Postfreeze-Thaw SamplesGiuseppe Lippi, Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis, 2013

- Influence of Residual Platelet Count on Routine Coagulation, Factor VIII, and Factor IX Testing in Postfreeze-Thaw SamplesGiuseppe Lippi, Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis, 2013

- Association Between Ratio of Fresh Frozen Plasma to Red Blood Cells During Massive Transfusion and Survival Among Patients Without Traumatic InjuryTomaz Mesar, JAMA Surgery, 2017

- Erythropoietin and Transfusions Among Critically Ill PatientsErythropoietin and Transfusions Among Critically Ill PatientsSean M. Bagshaw, Journal of American Medical Association, 2003

- Red Blood Cell Transfusion in the Intensive Care UnitSenta Jorinde Raasveld, Journal of American Medical Association, 2023

- RED CELL TRANSFUSIONS IN THE TREATMENT OF ANEMIA: A PRELIMINARY REPORTJournal of American Medical Association, 1943

- Efficacy of Recombinant Human Erythropoietin in Critically Ill Patients: A Randomized Controlled TrialHoward L. Corwin, Journal of American Medical Association, 2002

- Effect of restrictive versus liberal red cell transfusion strategies on haemostasis: systematic review and meta-analysis

| | Fig 1Incidence of adverse reactions in different study groups.|

| Fig 2 Types of adverse reactions in the study population.|

References

- Simon TL, McCullough J, Snyder EL. et al, eds. Rossi's Principles of Transfusion Medicine. 6th ed.. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2022: 617-623

- Connelly-Smith LS, Linenberger ML. eds. The collection and processing of hematopoietic progenitor cells. In: AABB Technical Manual. 20th ed.. MD: American Association of Blood Banks; 2020: 737-758

- Pamphilon D, Mijovic A. Storage of hemopoietic stem cells. Asian J Transfus Sci 2007; 1 (02) 71-76

- Wingard JR, Gastineau DA, Leather HL. et al, eds. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Handbook for Clinicians, 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: AABB; 2015: 228-231

- Truong TH, Moorjani R, Dewey D, Guilcher GM, Prokopishyn NL, Lewis VA. Adverse reactions during stem cell infusion in children treated with autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2016; 51 (05) 680-686

- Lecchi L, Giovanelli S, Gagliardi B, Pezzali I, Ratti I, Marconi M. An update on methods for cryopreservation and thawing of hemopoietic stem cells. Transfus Apheresis Sci 2016; 54 (03) 324-336

- Bakken AM. Cryopreserving human peripheral blood progenitor cells. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther 2006; 1 (01) 47-54

- Vidula N, Villa M, Helenowski IB. et al. Adverse events during hematopoietic stem cell infusion: analysis of the infusion product. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2015; 15 (11) e157-e162

- Devadas SK, Khairnar M, Hiregoudar SS. et al. Is long term storage of cryopreserved stem cells for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation a worthwhile exercise in developing countries?. Blood Res 2017; 52 (04) 307-310

- Mukhopadhyay A, Gupta P, Basak J. et al. Stem cell transplant: an experience from eastern India. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2012; 33 (04) 203-209

- Jain R, Hans R, Totadri S. et al. Autologous stem cell transplant for high-risk neuroblastoma: achieving cure with low-cost adaptations. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2020; 67 (06) e28273

- Setia RD, Arora S, Handoo A. et al. Outcome of 51 autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplants after uncontrolled-rate freezing (“dump freezing”) using -80°C mechanical freezer. Asian J Transfus Sci 2018; 12 (02) 117-122

- Cordoba R, Arrieta R, Kerguelen A, Hernandez-Navarro F. The occurrence of adverse events during the infusion of autologous peripheral blood stem cells is related to the number of granulocytes in the leukapheresis product. Bone Marrow Transplant 2007; 40 (11) 1063-1067

- Otrock ZK, Sempek DS, Carey S, Grossman BJ. Adverse events of cryopreserved hematopoietic stem cell infusions in adults: a single-center observational study. Transfusion 2017; 57 (06) 1522-1526

- Gokarn A, Tembhare PR, Syed H. et al. Long-term cryopreservation of peripheral blood stem cell harvest using low concentration (4.35%) dimethyl sulfoxide with methyl cellulose and uncontrolled rate freezing at -80 °C: an effective option in resource-limited settings. Transplant Cell Ther 2023; 29 (12) 777.e1-777.e8

- Solves P, Penalver M, Arnau MJ. et al. Adverse events after infusion of cryopreserved and non cryopreserved hematopoietic progenitor cells from different sources. Ann Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018; 1 (01) 1004

- Martín-Henao GA, Resano PM, Villegas JM. et al. Adverse reactions during transfusion of thawed haematopoietic progenitor cells from apheresis are closely related to the number of granulocyte cells in the leukapheresis product. Vox Sang 2010; 99 (03) 267-273

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share