Rare metastatic prostatic malignancy: A case report and approach to management

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2011; 32(04): 233-237

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/0971-5851.95149

Abstract

We present a patient with metastatic leiomyosarcoma of the prostate who achieved complete response with chemotherapy. A 70 years old male patient presented with urinary tract symptoms and a prostatic mass. After having been treated as carcinoma prostate, he presented with progressive pelvic mass, lung and bone metastases to our hospital. Repeat biopsy was suggestive of prostatic leiomyosarcoma. He was treated with chemotherapy with the ifosfamide-epirubicin regimen and achieved complete remission on positron emission tomography/computerized tomography after three cycles. He was given a total of six cycles of chemotherapy and continues to be disease-free after 8 months. Although adenocarcinomas are the commonest prostatic malignancies in the elderly, a careful evaluation is essential to rule out alternative diagnoses. Our case report illustrates the potential role of combination chemotherapy in the management of advanced leiomyosarcoma of the prostate. The literature on this entity is reviewed.

Keywords

Chemotherapy - leiomyosarcoma - positron emission tomography/computerized tomography - prostatePublication History

Article published online:

06 August 2021

© 2011. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

We present a patient with metastatic leiomyosarcoma of the prostate who achieved complete response with chemotherapy. A 70 years old male patient presented with urinary tract symptoms and a prostatic mass. After having been treated as carcinoma prostate, he presented with progressive pelvic mass, lung and bone metastases to our hospital. Repeat biopsy was suggestive of prostatic leiomyosarcoma. He was treated with chemotherapy with the ifosfamide-epirubicin regimen and achieved complete remission on positron emission tomography/computerized tomography after three cycles. He was given a total of six cycles of chemotherapy and continues to be disease-free after 8 months. Although adenocarcinomas are the commonest prostatic malignancies in the elderly, a careful evaluation is essential to rule out alternative diagnoses. Our case report illustrates the potential role of combination chemotherapy in the management of advanced leiomyosarcoma of the prostate. The literature on this entity is reviewed.

Though adenocarcinoma is the commonest prosatatic malignancy in elderly individuals, a significant minority may have spindle cell lesions, squamous cell or small cell carcinomas. It is essential to have a histological confirmation as the treatment and outcomes differ significantly. The following report describes a patient with leiomyosarcoma of the prostate and reviews the diagnostic and therapeutic approach for this rare malignancy.

A 70-year-old male presented with history of incomplete evacuation of bladder for 2 months. There were no symptoms of hesitancy, frequency, hematuria or pelvic pain. He was evaluated and detected to have a prostatic mass. Serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level was 10.4 ng/dl. He was diagnosed to have adenocarcinoma prostate on biopsy and was treated with injectable leuprolide, oral bicalutamide and orchiectomy.

He presented to our institute 2 months after orchiectomy with acute urinary retention requiring bladder catheterization. At presentation, the patient did not have any other complaints except for mild pain in the pelvis. His vitals were stable and he had ECOG performance status of 1. General and abdominal examination was unremarkable. Digital rectal examination suggested enlarged prostate with rectal mucosa infiltration. Investigations revealed normal biochemical and hematological parameters. Serum PSA at this time was 0.28 ng/dl.

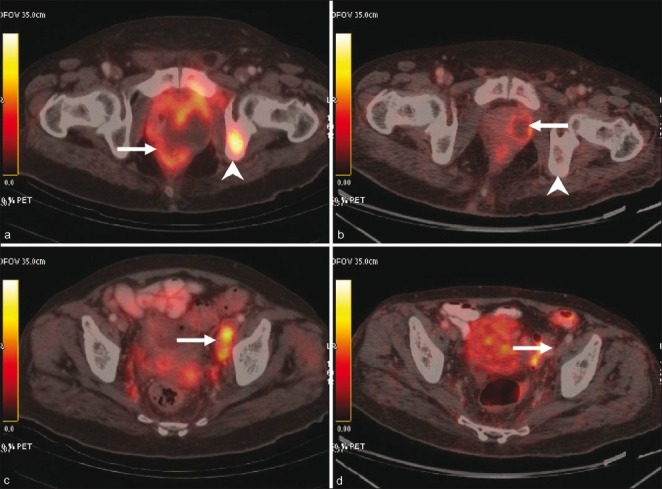

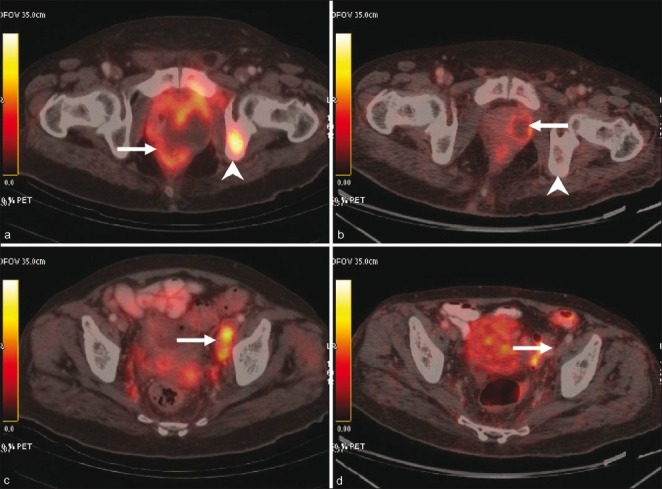

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) pelvis showed widely infiltrating mass in the left prostate with involvement of the bladder and rectum and pelvic lymphadenopathy. Imaging with fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computerized tomography (FDG-PET/CT) scan was done for metastatic work-up. PET/CT revealed a large heterogeneously enhancing mass involving the prostate gland, showing necrotic areas within along with ipsilateral enlarged hypermetabolic external iliac nodes, and a metastatic lesion in the left ischium as shown in Figure 1. The mass measured 7.5 cm in the anteroposterior diameter, 4.9 cm in the transverse diameter and 9.5 cm in the vertical diameter. The mass laterally abutted the ischiorectal fossae and anteriorly extended up to the pubic symphysis with infiltration of the adjacent periprostatic and perivesical fat. Multiple FDG-avid nodules (maximum SUV 3.3) were seen in bilateral lungs. An FDG-avid mass (maximum SUV 5.5) was seen in the right ventricle with thrombus in the right ventricle. A thrombus was also seen in the main pulmonary artery and the descending branch of the left pulmonary artery.

| Figure 1:Pre-treatment (a and c) and post-treatment (b and d) PET/CT images. A large necrotic mass is seen involving the prostate gland (arrow in a) with ipsilateral avid external iliac nodes (arrow in c). Also seen is a hypermetabolic focus in the left ischium (arrowhead in a), consistent with bone metastasis. Post-treatment images reveal significant regression of the mass in the prostate (arrow in b). Metastatic nodes and bone lesion are not visualized (arrow in b and arrowhead in d)Our patient was initially diagnosed and treated as adenocarcinoma prostate. However, in view of early progression of disease and poor response to the therapy that consisted of two lines of hormonal therapy, the possibility of an alternative diagnosis was considered and a repeat prostatic biopsy was done.

The biopsy showed tumor composed of sheets of large oval cells having abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and hyperchromatic large pleomorphic oval nuclei. Few bizarre tumor cells with occasional mitotic Figures were noted. Necrosis was seen without any definite pattern. Immunohistochemistry showed focal positivity for smooth muscle actin. The tissue was negative for epithelial membrane antigen, pancytokeratin, CD68, prostate-specific antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen and thyroid transcription factor-1. After reviewing the slides, a final diagnosis of epithelioid leiomyosarcoma of the prostate was rendered.

Management

After discussing the various options with the patient and reviewing the available literature, it was decided to offer the patient chemotherapy with a combination of Ifosfamide at 1600 mg/m2 and Epirubicin at 40 mg/m2 for 3 days each, repeated every 21 days. The patient developed non-life-threatening febrile neutropenia after the first cycle for which he needed admission and intravenous antibiotics. The subsequent cycles were given with 25% dose reduction and with primary granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) prophylaxis. There was significant symptomatic benefit in the pain after the first cycle of chemotherapy. Supportive therapy included A PET/CT was repeated after three cycles. There was significant reduction in the size and metabolic activity of the prostatic mass, with complete disappearance of the bony lesions, the pulmonary metastases and the myocardial deposit, suggestive of complete response to therapy. There was no myocardial deposit or ventricular dysfunction on echocardiography. In view of good response, he was given three more cycles subsequently which were well-tolerated except for grade 2 thrombocytopenia.

He has been on follow-up for the past 9 months and has been doing well with a good quality of life. Repeat PET/CT scans have shown the disease to be in complete remission.

Differential diagnosis

Adenocarcinomas are the commonest tumors arising in the prostate and increase in frequency with increasing age.[1] The detection of adenocarcinomas has increased dramatically in the western world with routine PSA screening. The usual presentation of prostatic malignancy is bladder outlet obstructive symptoms. Pain due to local spread or metastases is usually a late occurrence. The prognosis of localized disease varies with the stage of the disease and response to therapy. Patients with metastatic disease have a significantly worse outcome, with one study showing median progression-free survival of 18 months and overall survival of 30 months.

Small cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas of the prostate are infrequent and aggressive cancers. Since they are usually not associated with increased PSA, they are detected only when they become symptomatic and in an advanced stage. There are other rarer forms of prostate cancer that include sarcomas, intralobular acinar carcinomas, ductal carcinomas, small cell or scirrhous pattern tumors, a rare clear cell variant resembling renal cell carcinomas, sarcomas, mucinous carcinoma, and transitional cell carcinoma.

Spindle cell lesions of the prostate are rare malignancies and represent a diagnostically challenging and diverse array of entities.[2] The pathological features and distinguishing features are discussed below.

Benign proliferative disease may produce hesitancy, intermittent voiding, a diminished stream, incomplete emptying, and post-void leakage. Prostatitis often produces pain or induration. Typically, the symptoms remain stable over time and obstruction does not occur.

Pathological discussion

Spindle tumors on a prostatic biopsy encompass differential diagnosis of a wide range which includes prostatic stromal tumors and sarcomatoid carcinoma (carcinosarcoma) of the prostate. Lesions that may involve the prostate in addition to other anatomic sites include inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT), solitary fibrous tumor (SFT), smooth muscle tumors, and rhabdomyosarcoma. Extension of a rectal gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) may rarely involve the prostate and even present clinically as an intraprostatic mass. Finally, sclerosing adenosis may occasionally mimic a spindle cell neoplasm. Histomorphology of these entities may be overlapping, especially in a small biopsy specimen, and a panel of immunohistochemical markers may help in delineating these spindle neoplasms. Stromal tumors of the specialized prostatic stroma are broadly categorized into prostatic stromal proliferation of uncertain malignant potential (PSPUMP) and prostatic stromal sarcoma (PSS).[3] A majority of these lesions would be immunoreactive to vimentin and CD34, as also would be SFT and GIST. However, SMA and C-kit positivity in GIST and Bcl-2 in SFT additionally demarcate them from stromal sarcomas. IMT is known to express Alk-1 in up to 50% of cases which aids in their diagnosis.[4] Leiomyosarcomas (LMS) commonly react with SMA, desmin and h-caldesmon. In the present case, the epithelioid appearance may have led to an erroneous labeling as an adenocarcinoma. As a caveat, up to 38% of LMS can also express cytokeratin which may further cause diagnostic difficulties.[5] Thus, a careful pathological examination with an adequate immunohistochemistry panel is a must in all cases of suspected prostatic malignancy.

Radiological discussion

PET scanning with CT imaging has been extensively used in evaluating prostatic tumors. Almost all the studies are in prostatic carcinoma. 18FDG-PET has been found to have little accuracy in diagnosing and staging prostatic carcinoma.[6] Newer radiotracers like 11C-choline and 11C-acetate are good alternatives for staging metastatic disease, while 18F-fluoride is useful for bone disease. Currently, FDG-PET can be recommended for metastatic evaluation in equivocal cases. Further testing is needed on other radiotracers. Extensive research is needed to clarify the exact role PET/CT plays in the treatment of prostate cancer. There are no specific data regarding the role of PET/CT in other prostatic malignancies.

Prostatic leiomyosarcomas

Patients with prostatic LMS are usually elderly individuals in the sixth and seventh decades. The common presenting features include obstructive urinary features and perineal pain.[7] Recurrent hematuria, burning on micturition and painful ejaculation have also been reported. In one series, 23% of patients had metastatic disease at presentation. The lungs were the commonest organ involved with metastases, with liver and bones being the other sites of involvement. The work-up included CT scan of the abdomen and chest. Biopsy of the mass was confirmatory with most of the reported cases presenting with high-grade tumors with mitosis, necrosis and moderate to severe atypia.[8] The tumors on immunohistochemistry are usually positive for desmin, vimentin and actin and occasionally positive for cytokeratin.

LMS are aggressive tumors and have poor overall survival, especially in patients presenting with metastasis. Cheville et al. reviewed 23 cases over a 65-year period and had follow-up data in 14 patients.[7] Period of follow-up ranged from 3 to 72 months with a mean of 19 months. Ten of the 14 patients died of the disease with a mean duration of 22 months, while 3 patients remained alive with disease. Only one patient was alive and free of disease with a follow-up of 4.5 months. Sexton et al. published a series of 23 cases of prostatic sarcomas, which included 12 cases of LMS.[9] The overall survival in these patients ranged from 3 to 96 months. Among the patients with LMS, nine patients died due to disease, two remained disease-free at 12 months and 88 months, respectively, while one was lost to follow-up. There were four patients with metastatic disease who survived for 3, 5, 8 and 18 months, respectively. The patients with metastasis at presentation had a mean survival of 8.5 months compared to 39.5 months in non-metastatic patients. The only factors that correlated with better outcome in the whole cohort were absence of metastases at presentation and complete surgical resection with negative margins. Dotan et al. in their analysis of sarcoma patients in the Memorial Sloan Kettering documented 21 cases in the prostate with 8 cases of LMS.[10] They also showed that metastasis at presentation was associated with poor outcome, with an overall survival of 1.4 years as compared to 10.7 years. The only other factor that correlated with survival on multivariate analysis was tumor size. This analysis did not however focus on treatment and did not give details on prostatic LMS specifically. Other case series by Chen et al. (7 cases) and Ahlering (4 cases) showed similar poor survival in LMS.[11,12]

Multimodality treatment including surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy is the usual management for LMS. Surgery followed by adjuvant treatment with radiation and/or chemotherapy in patients with bulky disease or positive nodes appears to be the optimal treatment. Neoadjuvant treatment has also been used in patients with bulky disease. Various chemotherapy regimens have been used – usually anthracycline-based and incorporating cyclophosphamide or ifosfamide and the platinum compounds. At present, no clear recommendations can be given for treatment.

The role of PET/CT in our patient is also noteworthy. Multiple studies have established that PET/CT imaging is an important component in the staging, treatment and prognostication in sarcomas. The modality also allows discrimination between high- and low-grade sarcomas. PET/CT as an imaging modality has been studied extensively in carcinoma prostate. Generally, FDG-PET has a low detection rate in slow-growing tumors like prostatic carcinoma. To the best of our knowledge, the present report illustrates the first successful application of PET/CT in the staging and follow-up of prostatic LMS.

SUMMARY

Our patient was initially treated as carcinoma prostate with hormonal treatment. He presented within 4 months with extensive metastatic disease including cardiac metastasis and bone metastasis. Cardiac involvement and pulmonary thrombus were diagnosed on PET/CT, and to the best of our knowledge, have not been reported previously in literature. He received a combination of Epirubicin–Ifosfamide which has been previously administered in our institute as an adjuvant therapy in LMS prostate. Complete remission was achieved which has been rarely reported in the literature.

CONCLUSION

LMS of prostate is a rare malignancy that has poor prognosis, especially in metastatic setting. Our case report illustrates the potential role of combination chemotherapy in inducing complete remission in metastatic LMS prostate. The usefulness of PET/CT imaging in the staging and evaluation of response is also highlighted by the present study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Zelefisky MJ, Eastham JA, Sartor AO. Cancer of the prostate. In: Devita VT, Lawrenace PS, Rosenberg SA, Editors. Cancer: Principles and practices of oncology. 9 th Ed. Philndelphia; Lippincott, Willam, Wilkins. P. 1220-71.

- Hansel DE, Herawi M, Montgomery E, Epstein JI. Spindle cell lesions of the adult prostate. Mod Pathol 2007;20:148-58.

- Gaudin PB, Rosai J, Epstein JI. Sarcomas and related proliferative lesions of specialized prostatic stroma: A clinicopathologic study of 22 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1998;22:148-62.

- Gleason BC, Hornick JL. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours: Where are we now? J Clin Pathol 2008;61:428-37.

- Iwata J, Fletcher CD. Immunohistochemical detection of cytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigen in leiomyosarcoma: A systematic study of 100 cases. Pathol Int 2000;50:7-14.

- Rioja J, Rodríguez-Fraile M, Lima-Favaretto R, Rincón-Mayans A, Peñuelas-Sánchez I, Zudaire-Bergera JJ, et al. Role of positron emission tomography in urological oncology. BJU Int 2010;106:1578-94.

- Cheville JC, Dundore PA, Nascimento AG, Meneses M, Kleer E, Farrow GM, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the prostate. Report of 23 cases." Cancer 1995;76:1422-7.

- Vandoros GP, Manolidis T, Karamouzis MV, Gkermpesi M, Lambropoulou M, Papatsoris AG, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the Prostate: Case report and Review of 54 Previously Published Cases, Sarcoma 2008; article ID: 458709.

- Sexton WJ, Lance RE, Reyes AO, Pisters PW, Tu SM, Pisters LL. Adult prostate sarcoma: The M. D. Anderson cancer center experience. J Urol 2001;166:521-5.

- Dotan ZA, Tal R, Golijanin D, Snyder ME, Antonescu C, Brennan MF, et al. Adult genitourinary sarcoma: The 25-year Memorial Sloan-Kettering experience. J Urol 2006;176:2033-9.

- Chen HJ, Xu M, Zhang L, Zhang YK, Wang GM. Prostate sarcoma: A report of 14 cases. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue 2005;11:683-5.

- Ahlering TE, Weintraub P, Skinner DG. Management of adult sarcomas of the bladder and prostate. J Urol 1988;140:1397-9.

| Figure 1:Pre-treatment (a and c) and post-treatment (b and d) PET/CT images. A large necrotic mass is seen involving the prostate gland (arrow in a) with ipsilateral avid external iliac nodes (arrow in c). Also seen is a hypermetabolic focus in the left ischium (arrowhead in a), consistent with bone metastasis. Post-treatment images reveal significant regression of the mass in the prostate (arrow in b). Metastatic nodes and bone lesion are not visualized (arrow in b and arrowhead in d)

References

- Zelefisky MJ, Eastham JA, Sartor AO. Cancer of the prostate. In: Devita VT, Lawrenace PS, Rosenberg SA, Editors. Cancer: Principles and practices of oncology. 9 th Ed. Philndelphia; Lippincott, Willam, Wilkins. P. 1220-71.

- Hansel DE, Herawi M, Montgomery E, Epstein JI. Spindle cell lesions of the adult prostate. Mod Pathol 2007;20:148-58.

- Gaudin PB, Rosai J, Epstein JI. Sarcomas and related proliferative lesions of specialized prostatic stroma: A clinicopathologic study of 22 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1998;22:148-62.

- Gleason BC, Hornick JL. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours: Where are we now? J Clin Pathol 2008;61:428-37.

- Iwata J, Fletcher CD. Immunohistochemical detection of cytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigen in leiomyosarcoma: A systematic study of 100 cases. Pathol Int 2000;50:7-14.

- Rioja J, Rodríguez-Fraile M, Lima-Favaretto R, Rincón-Mayans A, Peñuelas-Sánchez I, Zudaire-Bergera JJ, et al. Role of positron emission tomography in urological oncology. BJU Int 2010;106:1578-94.

- Cheville JC, Dundore PA, Nascimento AG, Meneses M, Kleer E, Farrow GM, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the prostate. Report of 23 cases." Cancer 1995;76:1422-7.

- Vandoros GP, Manolidis T, Karamouzis MV, Gkermpesi M, Lambropoulou M, Papatsoris AG, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the Prostate: Case report and Review of 54 Previously Published Cases, Sarcoma 2008; article ID: 458709.

- Sexton WJ, Lance RE, Reyes AO, Pisters PW, Tu SM, Pisters LL. Adult prostate sarcoma: The M. D. Anderson cancer center experience. J Urol 2001;166:521-5.

- Dotan ZA, Tal R, Golijanin D, Snyder ME, Antonescu C, Brennan MF, et al. Adult genitourinary sarcoma: The 25-year Memorial Sloan-Kettering experience. J Urol 2006;176:2033-9.

- Chen HJ, Xu M, Zhang L, Zhang YK, Wang GM. Prostate sarcoma: A report of 14 cases. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue 2005;11:683-5.

- Ahlering TE, Weintraub P, Skinner DG. Management of adult sarcomas of the bladder and prostate. J Urol 1988;140:1397-9.

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share