Primary pediatric gastrointestinal lymphoma

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2011; 32(02): 92-95

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/0971-5851.89786

Abstract

Background: Primary non-Hodgkin′s lymphoma (NHL) of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is the most common extranodal lymphoma in pediatric age group. Yet, the overall incidence is very low. The rarity of the disease as well as variable clinical presentation prevents early detection when the possibility of cure exists. Materials and Methods: We studied six cases of primary GI NHL in pediatric age group with reference to their clinical presentation, anatomic distribution and histopathologic characteristics. Results: All were males except one. Intestinal obstruction was the presenting feature in 50%. Half the cases showed ileocaecal involvement, while large bowel was involved in 16%. Histology showed four cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), one case of Burkitt lymphoma, and one Burkitt-like lymphoma. Immunohistochemistry for Tdt, CD20, CD3, CD30, bcl2, bcl6 confirmed the morphological diagnosis. Conclusion: Pediatric GI lymphoma commonly involves the ileocaecal region and presents with intestinal obstruction. A higher prevalence of DLBCL is found compared to other series. A high proliferative index is useful in differentiating Burkitt-like lymphoma from DLBCL.

Publication History

Article published online:

06 August 2021

© 2011. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Background:

Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is the most common extranodal lymphoma in pediatric age group. Yet, the overall incidence is very low. The rarity of the disease as well as variable clinical presentation prevents early detection when the possibility of cure exists.

Materials and Methods:

We studied six cases of primary GI NHL in pediatric age group with reference to their clinical presentation, anatomic distribution and histopathologic characteristics.

Results:

All were males except one. Intestinal obstruction was the presenting feature in 50%. Half the cases showed ileocaecal involvement, while large bowel was involved in 16%. Histology showed four cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), one case of Burkitt lymphoma, and one Burkitt-like lymphoma. Immunohistochemistry for Tdt, CD20, CD3, CD30, bcl2, bcl6 confirmed the morphological diagnosis.

Conclusion:

Pediatric GI lymphoma commonly involves the ileocaecal region and presents with intestinal obstruction. A higher prevalence of DLBCL is found compared to other series. A high proliferative index is useful in differentiating Burkitt-like lymphoma from DLBCL.

INTRODUCTION

Primary tumors of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract are rare in children and represent less than 5% of all pediatric neoplasms.[1] The rarity of the disease and variable clinical presentation prevent early detection when the possibility of cure exists. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) remains the most common malignancy of the GI tract in children.[2] They usually have different anatomic distribution and histologic appearance compared to common patterns in adult cases. We studied six cases of primary GI lymphoma in pediatric age group with reference to clinical presentation, anatomic distribution and histopathologic characteristics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We studied six pediatric patients with provisional diagnosis of extranodal NHL in GI tract over a 3-year period. According to criteria developed by Dawson and colleagues, primary lymphoma of GI tract includes cases with no superficial adenopathy at diagnosis, no mediastinal adenopathy at chest radiography, normal blood cell counts, no involvement of liver and spleen, and involvement of only regional lymph nodes at laparotomy.[3] The presenting symptoms were registered; extent of disease was determined by history, physical examination, baseline complete hemogram, liver function tests, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) as a tumor bulk indicator, uric acid, serum electrolytes, bone marrow biopsy, abdominal ultrasound and/or contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) scan of the abdomen. All pathologic specimens were reviewed and classified according to World Health Organization (WHO) – REAL classification. Five-micron thick sections were cut and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H and E). Immunohistochemical staining for CD20, CD3, Tdt, Bcl2 and Bcl6 was performed. Ki67 index were determined in selected cases. The tumors were staged according to St. Jude's staging system.[4]

RESULTS

Six cases of pediatric GI lymphoma were identified over a period of 3 years. The age at presentation ranged from 1 to 8 years. All of these patients were boys except one girl child who presented at a very early age (1 year). The commonest presentation was intestinal obstruction present in three of the six (50%) patients. Other presentations included asymptomatic abdominal lump, abdominal pain, and pain along with vomiting. Ileocecal region was the most common site of involvement (50%) followed by terminal ileum (33%). Only one patient (16%) had involvement of the large gut in the region of sigmoid colon [Table 1].

Table 1

Clinical data, histopathology and staging of pediatric gastrointestinal lymphoma

Surgical resection was performed in all six patients and the gross specimen showed nodular growth ranging from 2.5 to 5 cm in diameter in four cases, and the remaining two had infiltrative growth involving cecum and sigmoid colon, respectively, with thickening of their walls. One of the lesions in the terminal ileum was accompanied by regional lymphadenopathy.

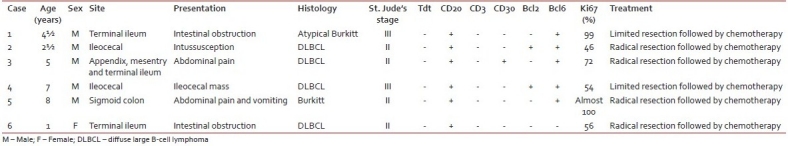

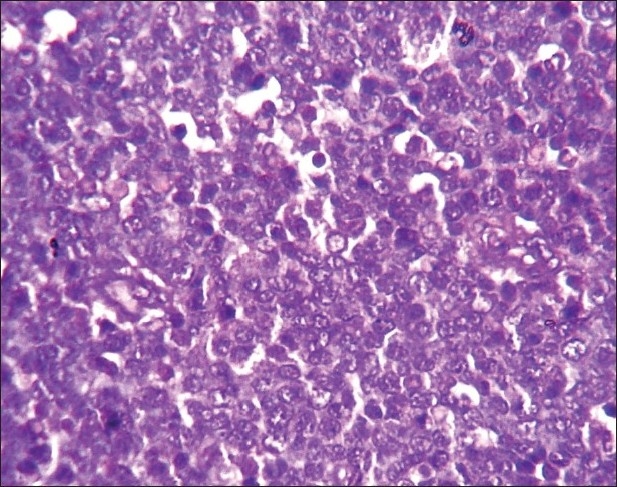

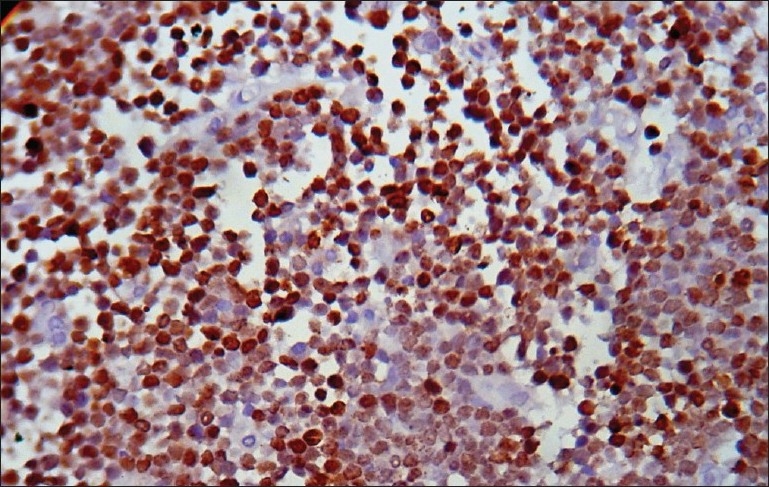

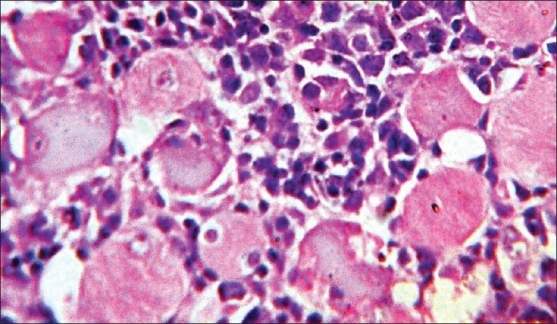

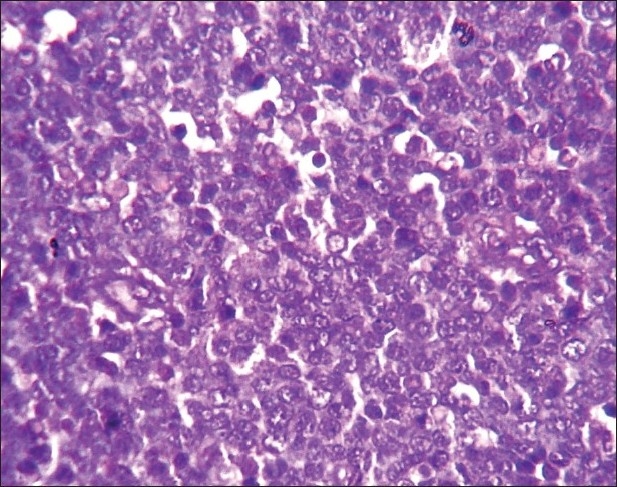

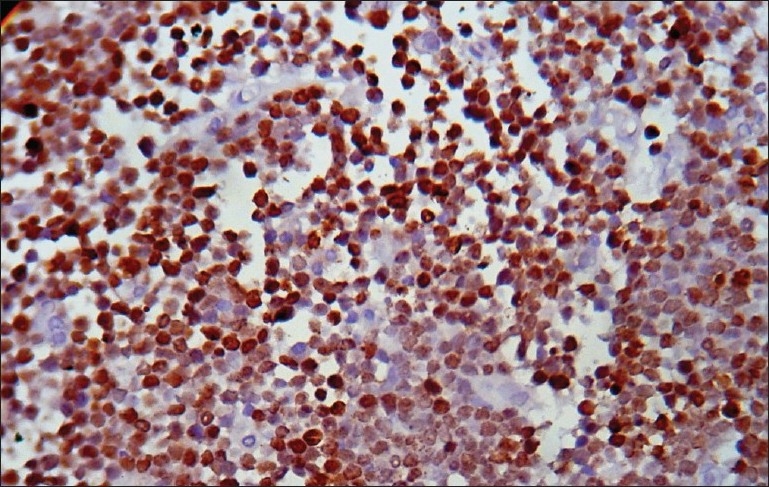

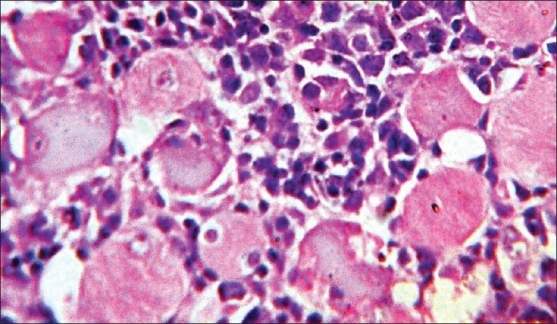

Histology of the lesions showed classical Burkitt lymphoma (BL) in one case with diffuse sheets of small tumor cells having round to oval nuclei and several prominent basophilic nucleoli. The chromatin was coarse and nuclear membrane was thick. This case showed a prominent starry-sky pattern [Figure 1]. The tumor was positive for B-cell marker CD20, negative for CD3, Tdt and showed a high proliferative index [Figure 2]. In the second case from terminal ileum, the cells were larger and more atypical with few binucleate forms. This tumor also showed a very high proliferative index and was diagnosed as atypical Burkitt. The remaining four cases showed histology of a diffuse large cell lymphoma and were positive for B-cell marker CD20 and negative for CD3 [Figure 3].

| Fig. 1 Photomicrograph showing the typical starry-sky appearance of a case of Burkitt lymphoma (H and E, ×400)

| Fig. 2 Photomicrograph showing high Ki67 index in a case of atypical Burkitt lymphoma (Ki67 immunostaining, ×400)

| Fig. 3 Photomicrograph showing CD20 positive cells in a case of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (CD20 immunostaining, ×400)

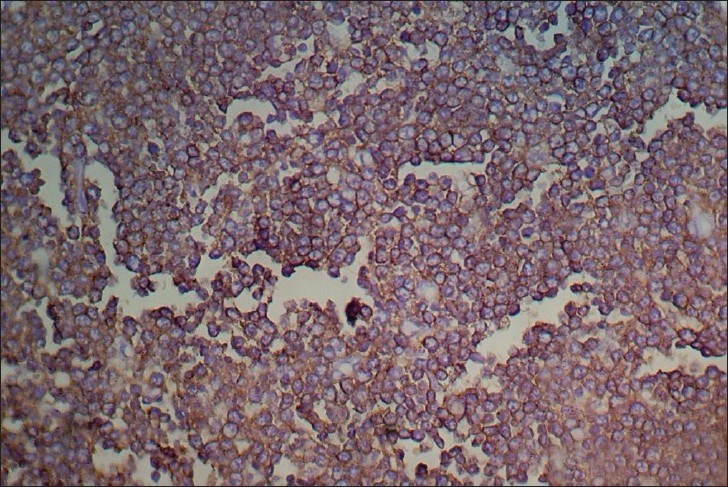

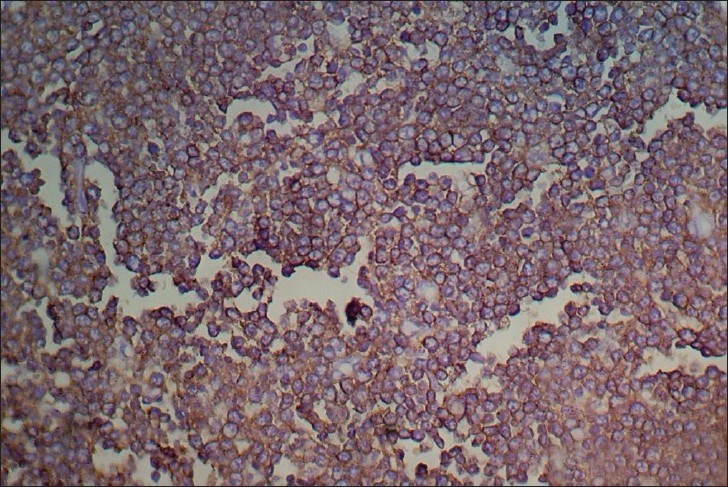

None of these patients showed generalized lymphadenopathy or involvement of bone marrow. Cutaneous nodules at a distant site were observed in two (33%) cases. The patient having atypical BL on histology developed a nodule on the lateral side of the back, approximately 2 cm in diameter, 15 days after the operative procedure. Another patient with primary ileocecal mass showed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) on histology and presented with a skin nodule over the abdominal wall, 1 month after surgery. On histology, this skin nodule was seen to be composed of diffuse sheets of tumor cells infiltrating the dermis, subcutaneous tissue and skeletal muscle [Figure 4]. LDH levels were increased in all the cases. The tumor staging was done according to the St. Jude's system for childhood NHL.[4] Four patients (66%) presented in stage II and the remaining two (33%) had stage III disease. Stage I and II tumors were subjected to primary radical resection followed by multiagent CHOP-like chemotherapy (six cycles). Patients in stage III were subjected to conservative surgery followed by chemotherapy. In the 3-year follow-up period, two of our patients died (one DLBCL and one atypical Burkitt). Both of them had stage III disease. The remaining four patients fared well during this 3-year period without any relapse. None of these patients developed tumor lysis syndrome during chemotherapy.

| Fig. 4 Photomicrograph showing diffuse infiltration of large lymphoid cells in between skeletal muscle fibers (H and E, ×400)

DISCUSSION

Malignant lymphomas are the third most common type of childhood cancer.[5] It is important to identify the distinction between NHLs of adults and those of children.[6] Children typically present with diffuse extranodal disease in contrast to adults among whom primary nodal disease is common. Primary GI malignancies are a rarity in children, with limited information from Asian population.[7]

The peak age for NHL of GI tract in children is 5–15 years.[8] Three patients in this present series presented below 5 years, with one of them presenting at 1 year. The patients presenting below 5 years are reported to have only marginally better outcome (5-year survival 82.9% compared to 76.9%).[9] Unlike adult patients in whom stomach is the most frequent site, small and large intestines are the most commonly involved sites in pediatric age group.[10] Five out of six patients in the present study had involvement of small intestine with colonic involvement in only one case. The male to female ratio of childhood GI NHL is reported to be from 7:1 to 1.8–2.5: 1.[2,9] There was only one female child amongst the six cases in our series. Clinically, the patients presented with varied symptoms ranging from abdominal mass to acute abdominal emergency caused by intussusception. The commonest presenting symptom is reported to be abdominal pain (81.4%), followed by abdominal swelling, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, and intestinal obstruction.[9] In our patients, intestinal obstruction was the commonest mode of presentation.

Nearly 50% of children with GI NHL have tumor infiltrates confined to GI tract with possible regional lymph node involvement.[2] In the present series, all six patients had intestinal growth with two of them showing regional lymph node involvement. Two patients developed cutaneous nodules, one over the back and other over the abdominal wall. Subcutaneous nodules are very rare in BL and DLBCL.[10,11] Seeding of skin and subcutaneous tissue after surgical procedure with subsequent rapid growth have been reported in BL cases. Seeding has been documented in one case of abdominal BL. However, satellite lesions and regional metastasis not directly communicating with the main tumor have also been reported in an area distal to the previous surgical field.[10] Similarly, in our case, the site of the nodule was distant from the site of surgery. Recently, a case of gastric DLBCL with cutaneous involvement has also been reported.[12] According to St. Jude's staging system, four of them had stage II and two had stage III disease. Other studies have also found tumors presenting in stage II as well as in stage III and IV disease with significant survival advantage in stage II compared to stage III and IV.[13] All six patients in this series did well in the postoperative period and all of them were given systemic chemotherapy. Histologically, four of our cases were diagnosed as DLBCL based on cellular morphology and immunohistochemistry. In a study from Pakistan, they have noticed predominance of high-grade lymphomas with diffuse large B-cell, Burkitt and Burkitt-like lymphoma.[7] Western literature also reports a high incidence of BL but a lower incidence of DLBCL.[9] Out of six cases we encountered, only one case of BL and one terminal ileal growth was diagnosed as “Burkitt-like lymphoma”. The diagnosis was based on neoplastic cells showing wider range of nuclear size and shape along with fewer and larger nucleoli.[14] These cellular features lead to difficulties in differentiating these variants from large B-cell lymphoma. The WHO committee suggests that a Burkitt-like lymphoma diagnosis should be made in tumors with morphologic features intermediate between BL and DLBCL, in which Ki67 fraction of viable cells is at least 99% or a c-MYC translocation is present.[14] The case of Burkitt-like lymphoma in the present series showed a very high proliferative index.

The ideal treatment approach in GI lymphoma remains controversial. Surgical resection should always be attempted for localized disease. The approach to extensive gut lymphoma varies widely amongst physicians. A conservative approach consists of limited resection of obstructed or perforated segment, followed by whole abdomen radiation. However, several authors have argued for aggressive surgical debulking of all intestinal lymphomas, including stage III or IV disease.[15,16] Radical tumor resection followed by chemotherapy in early disease, and limited or no resection followed by polychemotherapy in advanced disease may be the justified approach. However, recent studies have proposed the use of chemotherapy alone as an effective treatment option in primary GI lymphoma in all stages.[17] Larger randomized studies with long follow-up are required to reach a consensus regarding the treatment of primary GI lymphoma. Despite controversies regarding treatment, the disease stage at presentation remains the most important criterion determining survival.[18] In the present study, only patients with stage III disease had poor outcome. Histologic type of the disease did not affect the survival. Whether this could be due to the limited resection offered to these patients cannot be commented on. This would need a larger sample with randomized therapeutic approach.

To conclude, we noticed a higher prevalence of DLBCL amongst primary pediatric GI lymphomas. Another study from an Asian perspective had shown similar results.[7] However, the number of cases in our study is small and studies with large number of patients are required to substantiate these findings in the Indian context. In addition, one should be careful to differentiate Burkitt-like lymphoma from cases of DLBCL. Detailed study of morphology, immunohistochemistry and proliferative index would help in solving that issue.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

| Fig. 1 Photomicrograph showing the typical starry-sky appearance of a case of Burkitt lymphoma (H and E, ×400)

| Fig. 2 Photomicrograph showing high Ki67 index in a case of atypical Burkitt lymphoma (Ki67 immunostaining, ×400)

| Fig. 3 Photomicrograph showing CD20 positive cells in a case of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (CD20 immunostaining, ×400)

| Fig. 4 Photomicrograph showing diffuse infiltration of large lymphoid cells in between skeletal muscle fibers (H and E, ×400)

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share