Primary Hepatoid Adenocarcinoma of the Lung: A Study of Two Cases with Review of Literature

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2020; 41(04): 591-595

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/ijmpo.ijmpo_245_19

Abstract

Primary hepatoid adenocarcinoma (HAC) is a rare extrahepatic adenocarcinoma with morphological and phenotypical resemblance to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). It can occur in lung, stomach, gallbladder, pancreas, ovary, and uterus, with most common site being stomach. Morphological features of primary HAC of the lung are similar to HCC, so exclusion of metastatic HCC is necessary. In this report, we describe two cases of elderly men with primary pulmonary HAC who presented in advanced clinical stage and diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration cytology with immunohistochemistry. Both patients succumbed to death despite starting first cycle of chemotherapy.

Keywords

Cell block - fine-needle aspiration cytology - hepatoid adenocarcinoma - immunohistochemistry - lungPublication History

Received: 04 December 2019

Accepted: 30 June 2020

Article published online:

17 May 2021

© 2020. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Primary hepatoid adenocarcinoma (HAC) is a rare extrahepatic adenocarcinoma with morphological and phenotypical resemblance to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). It can occur in lung, stomach, gallbladder, pancreas, ovary, and uterus, with most common site being stomach. Morphological features of primary HAC of the lung are similar to HCC, so exclusion of metastatic HCC is necessary. In this report, we describe two cases of elderly men with primary pulmonary HAC who presented in advanced clinical stage and diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration cytology with immunohistochemistry. Both patients succumbed to death despite starting first cycle of chemotherapy.

Keywords

Cell block - fine-needle aspiration cytology - hepatoid adenocarcinoma - immunohistochemistry - lungIntroduction

Primary hepatoid adenocarcinoma (HAC) is a rare extrahepatic adenocarcinoma that is defined by morphological and functional hepatic differentiation.[1] The most common site of origin is stomach (63%). It rarely involves ovary (10%), lung (5%), gallbladder (4%), pancreas (4%), and uterus (4%).[2] There are only 34 cases of primary HAC of the lung origin that are described in the world literature, of which only one case has been reported from India.[3] In our study, we report two cases of primary HAC of the lung in two male patients which was diagnosed on fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) with ancillary studies. The present study, to best of our knowledge, is the second to report with the comprehensive clinicopathological data of two cases of primary HAC of the lung in the Indian literature.

Case Reports

Case 1

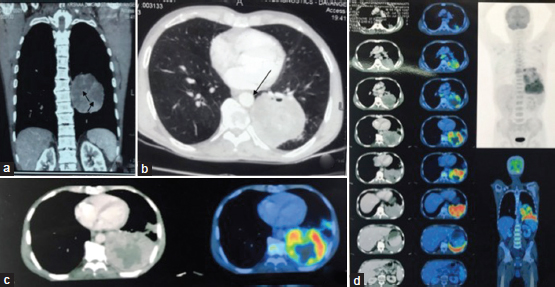

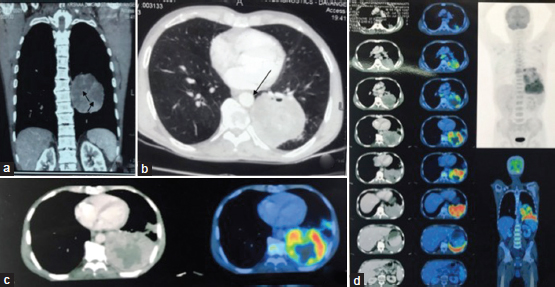

A 66-year-old male chronic smoker presented with chief complaints of pain in the left side of the chest for 2 months with a history of loss of weight and appetite. General physical examination was normal with no peripheral lymphadenopathy. Respiratory system examination showed decreased air entry in the left lung. On percussion, tenderness was noted over the left chest wall. Hematological investigations showed neutrophilic leukocytosis. Biochemical investigations were within normal limits. Serological tests for HIV and hepatitis B were negative. Chest X-ray posteroanterior view revealed an irregular, spiculated large lesion in the lower lobe of the left lung, suggestive of malignancy and ill-defined radiopaque lesion in the mid zone suggestive of consolidation. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the chest and thorax showed a large heterogeneously enhancing mass lesion measuring 7.6 cm × 7.5 cm × 7.5 cm with nonenhancing areas of necrosis in the superior segment of the lower lobe of the left lung with narrowing of bronchial lumina. The lesion was abutting left inferior pulmonary vein anteriorly, descending aorta medially, and posterior chest wall posteriorly [Figure 1]a] and [Figure 1]b]. Mediastinal lymphadenopathy and pleural effusion were not seen. On bronchoscopy, mucosal edema and narrowing of lumina were noted in the left bronchus. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid for cytology revealed numerous endobronchial cells with no evidence of malignancy, and the culture was positive for Pseudomonas putida. Acid-fast bacilli were not detected in the early morning sputum and BAL analysis.

| Figure 1:(a and b) Computed tomography chest and thorax coronal and axial images showing a large heterogeneously enhancing mass lesion with nonenhancing areas of necrosis (arrowheads) in the superior segment of the left lower lobe with narrowing of bronchial lumina (arrow). (c) Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography showing metabolically active lesion in the lower lobe of the left lung corresponding to tumor shown in computed tomographic image. Central necrotic tumor is metabolically inactive. (d) Multiple serial sections from thorax, abdomen–pelvis showing abnormal uptake in the left lung lower lobe with a few lung nodules and hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes (arrow), representing metastasis. There is no active lesion in the liver or any other organ suggesting lung as primary site of tumor

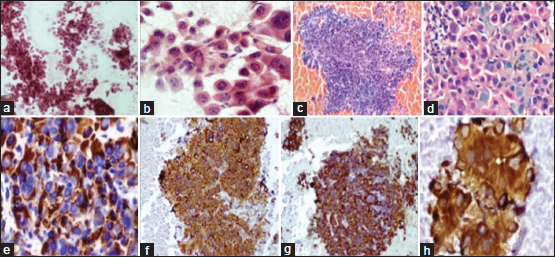

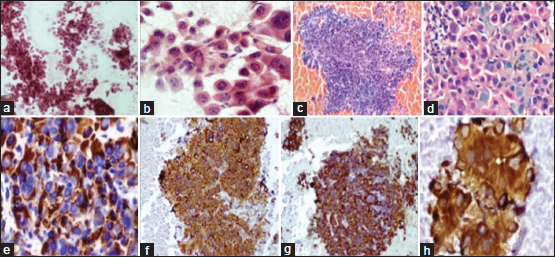

Computed tomography (CT)-guided biopsy was done from the mass lesion. Biopsy tissue was scanty showing large neoplastic cells arranged in the trabeculae pattern with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and vesicular nucleus. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) showed neoplastic cells expressing cytoplasmic immunoreactivity to thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) and negative for CK7 and P40. As tissue was inadequate for further IHC markers, the patient was referred for FNAC and cell block study. Ultrasonography (USG)-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) from lung lesion was done. Cytomorphology showed tumor cells in the clusters and discohesive cells. Tumor cells had moderate cytoplasm and vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli with intranuclear inclusions in few cells [Figure 2]a] and [Figure 2]b]. Cell block showed neoplastic cells arranged in cords and trabeculae [Figure 2]c] and [Figure 2]d]. IHC was performed on cell block and showed neoplastic cells to be positive for CK, Hep Par-1, and TTF-1 (cytoplasmic) and negative for CK7, CK20, napsin, and p40 [Figure 2]e], [Figure 2]e],[Figure 2]f],[Figure 2]g]. In view of Hep Par-1 positivity, serum alpha fetoprotein (AFP) and CECT abdomen were suggested to look for primary malignancy in the liver. Serum AFP level was elevated to 394.60 IU/ml. CECT abdomen and pelvis showed normal liver with no focal lesion. Other intra-abdominal and pelvic organs were normal. Second panel of IHC markers on cell block was advised which revealed tumor cells to be positive for AFP [Figure 2]h] and negative for arginase and CK5/6. Correlating with clinical and radiological findings, final impression of hepatoid variant of adenocarcinoma of the left lung was given.

| Figure.2:(a) Ultrasonography-guided lung fine-needle aspiration showing infiltrating neoplastic cells arranged in trabecular pattern and small clusters (PAP, ×100). (b) High magnification showing polygonal malignant cells with large amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm, central vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli (PAP, ×400) (c) Cell block of fine needle aspirate from the left lung mass showing neoplastic cells in hemorrhagic background (H and E × 40). (d) High magnification displaying round-to-polygonal cells with abundant cytoplasm, vesicular-to-hyperchromatic nucleus, some showing prominent nucleoli (H and E, ×400). (e-h) Immunohistochemistry on cell block showing diffuse positivity for Hep Par-1 (e), cytokeratin (f), thyroid transcription factor-1 (g), and alpha fetoprotein (h)

Further metastatic workup showed normal skeletal scintigraphy; glomerular filtration rate values were within normal limits. Positron emission tomography (PET)-CT showed metabolically active lesion in the lower lobe of the left lung with a few lung nodules and lymph nodes (hilar and mediastinal), representing carcinoma lung with metastasis. The patient was assigned clinical stage cT3N2M0 (Stage IIIA). No other visceral or skeletal metastasis was seen [Figure 1]c] and [Figure 1]d]. Chemotherapy was started; however, unfortunately, the patient succumbed to the disease after first cycle of chemotherapy.

Case 2

A 65-year-old man presented with chief complaints of pain in the right side of the chest and breathlessness for 2 months. He was a chronic smoker for 20 years and had a history of recent significant weight loss and loss of appetite. General physical examination was normal, except for pallor. Respiratory system examination revealed decreased air entry in the right lung and audible crypts. Right chest wall tenderness was noted on percussion. Laboratory investigations, hemogram, and biochemical tests were within normal limits. Serology for hepatitis B virus and HIV were nonreactive. Chest X-ray posteroanterior view revealed a large lesion in the right upper zone, suggestive of malignancy. CECT thorax showed a heterogeneously enhancing lesion measuring 6.5 cm × 4.5 cm × 6.6 cm in the posterior segment of the upper lobe of the right lung with extension into apical segment. The lesion was extending along major fissure up to lateral costal pleura and right hilar region. Anteriorly, it was abutting the trachea, right main bronchus, right upper lobe bronchus, azygos vein, and superior vena cava. Posteriorly, the lesion was abutting the T3, T4, T5, and T6 vertebral bodies and the corresponding posterior aspect of 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th ribs. Mediastinal lymph nodes were enlarged largest measuring 7.3 mm. A very tiny hypodense lesion of size 0.3 cm was noted in the liver segment Iva, suggestive of nonspecific inflammation. Bilateral kidneys showed multiple subcentimetric simple cysts.

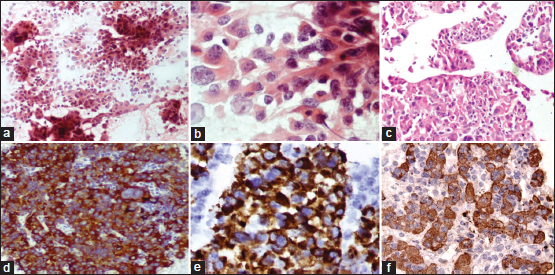

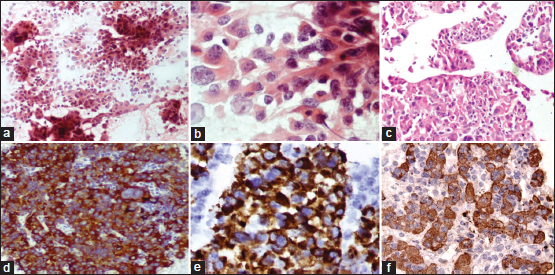

USG-guided FNA of the lung mass was done. Cytomorphology was similar to previous case [Figure 3]a], [Figure 3]b], [Figure 3]c]. IHC was performed on cell block and neoplastic cells were positive for CK, CK7, and TTF-1 (granular cytoplasmic) and negative for CK20, p40, and napsin [Figure 3]d], [Figure 3]e], [Figure 3]f]. Further, IHC markers were advised, for which clinicians decided to do biopsy since cell block tissue was scanty. IHC on tissue biopsy showed neoplastic cells immunoreactive for CK7, AFP, and Hep Par-1 with cytoplasmic positivity for TTF-1. Serum AFP level was raised (993.6 IU/ml). In view of raised serum AFP and its classical immunoreactivity in tumor cells in the absence of significant liver lesion, a diagnosis of primary HAC right lung was made. Further metastatic workup showed normal skeletal scintigraphy. A clinical stage cT2bN2M0 (Stage IIIA) was assigned to the patient. Chemotherapy was started, but the patient expired.

| Figure.3:(a) Ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration of the lung lesion showing tumor cells in clusters and few discohesive cells (PAP, ×100) (b) High magnification showing tumor cells with large amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm, central vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli (PAP, ×400). (c) cell block section showing tumor cells with focal sinusoidal pattern of arrangement (H and E, ×100); (d-f) immunohistochemistry on cell block showing positivity for CK7 (d), thyroid transcription factor-1 (e), Hep Par-1 (f)

Discussion

Primary HAC is a rare extrahepatic adenocarcinoma that is defined by morphological and functional hepatic differentiation.[1] This entity was descriptively termed as “hepatoid” due to the morphological appearance, and it should be differentiated from other adenocarcinomas.[4] The most common site of origin is stomach (63%). It rarely involves ovary (10%), lung (5%), gallbladder (4%), pancreas (4%), and uterus (4%).[2] HAC of the lung origin was first described by Ishikura et al. in 1990.[4] They proposed two criteria which were adopted uniformly for diagnosis of HAC:

-

Adenocarcinomatous component composed of neoplastic cells in the tubular or papillary architecture

-

Hepatoid component resembling hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC); the neoplastic cells containing abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with centrally placed nucleus. These cells are responsible for AFP production. Our both cases fulfilled all criteria.

A comprehensive search was conducted on PubMed, Google, and Google Scholar using terms of “hepatoid adenocarcinoma lung,” hepatoid carcinoma lung,” and “AFP producing tumor lung.” We found that only 34 cases of primary HAC lung have been reported in the world literature before December 2018.[3],[4],[5],[6],[7],[8],[9],[10],[11],[12],[13] Grossman et al. reviewed 28 cases of HAC lung reported in the English literature, between January 1980 and June 2015.[5] Additional six case reports have been published from June 2015 to December 2018 including one Indian case report by Vellaisamy et al. [3]

In these reported 34 cases of primary HAC lung, 33 were males with age ranging from 36 to 77 years (mean 57 years). History of chronic smoking was significant in 19 cases, suggesting that this neoplasm is common in middle to old age men and chronic smoking can be a predisposing factor. In the present report, the clinical features, smoking habit, signs, and symptoms of airway obstruction are similar to the world literature. Primary HAC is a very aggressive tumor with most of the patients presenting with higher stage of disease, distant metastasis, and shorter survival.[5] The maximum survival of 9 years was reported by Haninger et al. in a female with stage T1A HAC.[1]

Regarding the cell of origin of primary HAC, following hypotheses were adopted:

-

Embryologically, lung, liver, and stomach derived from the primitive foregut. It is hypothesized that hepatoid differentiation may occur at many diverse sites (stomach being most common) as another direction of differentiation of primitive neoplastic cells in adenocarcinoma[14]

-

The theory of “ectopic hepatoma” postulated that HAC in the lung arises from ectopic germ cells or liver cells in the lung or respiratory epithelium progenitors.[8] These hepatoid cells are AFP immunoreactive and responsible for AFP production which is used as one of the diagnostic criteria and useful indicator to monitor tumor progression and response to treatment.[4] In the present study, both cases showed elevated AFP levels.

Morphological features of primary HAC of the lung are similar to HCC, so exclusion of metastatic HCC is necessary before calling it as of lung origin.[1] Multislice CT abdomen or PET-CT abdomen are reliable investigations to rule out metastatic HCC by documenting the absence of liver lesion.[8] Although there are no specific imaging features to diagnose HAC directly, certain features are of concern such as detection of inhomogeneous areas and large necrotic areas on CT.[10] Hence, imaging for detection has a limited role but serves useful in the selection of a therapeutic schedule for HAC, as it is able to detect lymph node or distant metastases and help to assess the clinical stage.[9] In the present study, both cases showed heterogeneous areas with the first one having necrotic areas and the second one being extending to costal pleura. The first case has no lesion in liver; however, other case showed a tiny 3 mm lesion in the liver having nonspecific inflammatory etiology.

Distinguishing between HAC and HCC is important, especially in areas with a high incidence of chronic hepatitis B, chronic hepatitis C, and HCC. When there are concomitant lesions in the lung and liver, it is difficult to differentiate primary HAC from HCC metastasis on morphologic grounds alone. Differences in immunohistochemical expression of certain markers would be of considerable help though HAC shows immunophenotype similar to HCC. CK8, CK18, AFP, Hep Par-1, and TTF1 (cytoplasmic) are positive whereas CK5/6 and CK20 are negative in both HAC and HCC.[1],[15] CK7 can be negative[16] or positive in HAC.[1],[15] Some antibodies used to differentiate HAC from HCC are EpCAM markers such as HEA125, MOC31 and monoclonal CEA and CK19 which are positive in HAC but negative in HCC.[1],[2],[17] In the present report, primary HCC was ruled out primarily by radiological investigations since IHC markers which help to distinguish HCC from HAC are not available with us. Pattern of TTF-1 staining which is cytoplasmic is useful to distinguish HAC from conventional adenocarcinoma of the lung.[1]

Primary modality of treatment depends on stage of tumor. Early-stage HAC lung was treated primarily by resection of tumor followed by chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Advanced-stage neoplasm with poor resectability is given chemotherapy and radiotherapy only.[5]

Primary HAC is an uncommon malignancy and lung is the rare site of occurrence. Clinically, the patient presents at late stage of disease with poor survival. Morphologically, primary HAC lung resembles HCC from liver, and therefore, it is important to differentiate between these two entities by IHC and/or radiological investigations as prognosis and treatment may differ. Metastatic carcinoma from HAC should be included in the differential diagnosis in older patients with elevated serum AFP level and hepatic masses with imaging features of HCC in the absence of risk factors of HCC.[18]

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Haninger DM, Kloecker GH, Bousamra Ii M, Nowacki MR, Slone SP. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung: Report of five cases and review of the literature. Mod Pathol 2014; 27: 535-42

- Metzgeroth G, Ströbel P, Baumbusch T, Reiter A, Hastka J. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma-Review of the literature illustrated by a rare case originating in the peritoneal cavity. Onkologie 2010; 33: 263-9

- Devaraj U, Vellaisamy G, Crasta J. Primary hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Postgrad Med Edu Res 2016; 50: 103-6

- Ishikura H, Kanda M, Ito M, Nosaka K, Mizuno K. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma: A distinctive histological subtype of alpha-fetoprotein-producing lung carcinoma Virchows Archiv A, Pathological Anat. Histopathol 1990; 417: 73-80

- Grossman K, Beasley MB, Braman SS. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung: Review of a rare form of lung cancer. Respir Med 2016; 119: 175-9

- Motooka Y, Yoshimoto K, Semba T, Ikeda K, Mori T, Honda Y. et al. Pulmonary hepatoid adenocarcinoma: Report of a case. Surg Case Rep 2016; 2: 1

- Shao Y, Zhong DS, Wang D, Ma L. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung: A case report. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2016; 9: 4067-72

- Esa NY, Zamrud R, Bakar NS, Eezamuddeen MA, Hamdan MF. Is it liver or lung cancer? An intriguing case of lung adenocarcinoma with hepatoid differentiation. Proceedings of Singapore Healthc 2018; 27: 55-8

- Sun JN, Zhang BL, Li LK, Yu HY, Wang B. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung without production of α-fetoprotein: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Letters 2016; 12: 189-94

- Wu Z, Upadhyaya M, Zhu H, Qiao Z, Chen K, Miao F. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma: computed tomographic imaging findings with histopathologic correlation in 6 cases. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2007; 31: 846-52

- Nakashima K, Okagawa T. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung with high serum AFP and CEA values; Report of a case. Kyobu Geka 2018; 71: 76-9

- Khozin S, Roth MJ, Rajan A, Smith K, Thomas A, Berman A. et al. Hepatoid carcinoma of the lung with anaplastic lymphoma kinase gene rearrangement. J Thorac Oncol 2012; 7: e29-31

- Cavalcante LB, Felipe-Silva A, de Campos FP, Martines JA. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung. Autops Case Rep 2013; 3: 5-14

- Shaib W, Sharma R, Mosunjac M, Farris 3rd AB, El Rayes B. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung: A case report and review of the literature. J Gastrointest Cancer 2014; 45: 99-102 (Suppl 1)

- Che YQ, Wang S, Luo Y, Wang JB, Wang LH. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung: Presenting mediastinal metastasis without transfer to the liver. Oncol Lett 2014; 8: 105-10

- Karayiannakis AJ, Kakolyris S, Giatromanolaki A, Courcoutsakis N, Bolanaki H, Chelis L. et al. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder: Case report and literature review. J Gastrointest Cancer 2012; 43 Suppl 1: S139-44

- Su JS, Chen YT, Wang RC, Wu CY, Lee SW, Lee TY. Clinicopathological characteristics in the differential diagnosis of hepatoid adenocarcinoma: A literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19: 321-7

- Jo JM, Kim JW, Heo SH, Shin SS, Jeong YY, Hur YH. Hepatic metastases from hepatoid adenocarcinoma of stomach mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Mol Hepatol 2012; 18: 420-3

Address for correspondence

Publication History

Received: 04 December 2019

Accepted: 30 June 2020

Article published online:

17

May

2021

© 2020. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301

UP,

India

| Figure 1:(a and b) Computed tomography chest and thorax coronal and axial images showing a large heterogeneously enhancing mass lesion with nonenhancing areas of necrosis (arrowheads) in the superior segment of the left lower lobe with narrowing of bronchial lumina (arrow). (c) Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography showing metabolically active lesion in the lower lobe of the left lung corresponding to tumor shown in computed tomographic image. Central necrotic tumor is metabolically inactive. (d) Multiple serial sections from thorax, abdomen–pelvis showing abnormal uptake in the left lung lower lobe with a few lung nodules and hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes (arrow), representing metastasis. There is no active lesion in the liver or any other organ suggesting lung as primary site of tumor

| Figure.2:(a) Ultrasonography-guided lung fine-needle aspiration showing infiltrating neoplastic cells arranged in trabecular pattern and small clusters (PAP, ×100). (b) High magnification showing polygonal malignant cells with large amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm, central vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli (PAP, ×400) (c) Cell block of fine needle aspirate from the left lung mass showing neoplastic cells in hemorrhagic background (H and E × 40). (d) High magnification displaying round-to-polygonal cells with abundant cytoplasm, vesicular-to-hyperchromatic nucleus, some showing prominent nucleoli (H and E, ×400). (e-h) Immunohistochemistry on cell block showing diffuse positivity for Hep Par-1 (e), cytokeratin (f), thyroid transcription factor-1 (g), and alpha fetoprotein (h)

| Figure.3:(a) Ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration of the lung lesion showing tumor cells in clusters and few discohesive cells (PAP, ×100) (b) High magnification showing tumor cells with large amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm, central vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli (PAP, ×400). (c) cell block section showing tumor cells with focal sinusoidal pattern of arrangement (H and E, ×100); (d-f) immunohistochemistry on cell block showing positivity for CK7 (d), thyroid transcription factor-1 (e), Hep Par-1 (f)

References

- Haninger DM, Kloecker GH, Bousamra Ii M, Nowacki MR, Slone SP. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung: Report of five cases and review of the literature. Mod Pathol 2014; 27: 535-42

- Metzgeroth G, Ströbel P, Baumbusch T, Reiter A, Hastka J. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma-Review of the literature illustrated by a rare case originating in the peritoneal cavity. Onkologie 2010; 33: 263-9

- Devaraj U, Vellaisamy G, Crasta J. Primary hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Postgrad Med Edu Res 2016; 50: 103-6

- Ishikura H, Kanda M, Ito M, Nosaka K, Mizuno K. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma: A distinctive histological subtype of alpha-fetoprotein-producing lung carcinoma Virchows Archiv A, Pathological Anat. Histopathol 1990; 417: 73-80

- Grossman K, Beasley MB, Braman SS. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung: Review of a rare form of lung cancer. Respir Med 2016; 119: 175-9

- Motooka Y, Yoshimoto K, Semba T, Ikeda K, Mori T, Honda Y. et al. Pulmonary hepatoid adenocarcinoma: Report of a case. Surg Case Rep 2016; 2: 1

- Shao Y, Zhong DS, Wang D, Ma L. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung: A case report. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2016; 9: 4067-72

- Esa NY, Zamrud R, Bakar NS, Eezamuddeen MA, Hamdan MF. Is it liver or lung cancer? An intriguing case of lung adenocarcinoma with hepatoid differentiation. Proceedings of Singapore Healthc 2018; 27: 55-8

- Sun JN, Zhang BL, Li LK, Yu HY, Wang B. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung without production of α-fetoprotein: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Letters 2016; 12: 189-94

- Wu Z, Upadhyaya M, Zhu H, Qiao Z, Chen K, Miao F. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma: computed tomographic imaging findings with histopathologic correlation in 6 cases. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2007; 31: 846-52

- Nakashima K, Okagawa T. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung with high serum AFP and CEA values; Report of a case. Kyobu Geka 2018; 71: 76-9

- Khozin S, Roth MJ, Rajan A, Smith K, Thomas A, Berman A. et al. Hepatoid carcinoma of the lung with anaplastic lymphoma kinase gene rearrangement. J Thorac Oncol 2012; 7: e29-31

- Cavalcante LB, Felipe-Silva A, de Campos FP, Martines JA. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung. Autops Case Rep 2013; 3: 5-14

- Shaib W, Sharma R, Mosunjac M, Farris 3rd AB, El Rayes B. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung: A case report and review of the literature. J Gastrointest Cancer 2014; 45: 99-102 (Suppl 1)

- Che YQ, Wang S, Luo Y, Wang JB, Wang LH. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung: Presenting mediastinal metastasis without transfer to the liver. Oncol Lett 2014; 8: 105-10

- Karayiannakis AJ, Kakolyris S, Giatromanolaki A, Courcoutsakis N, Bolanaki H, Chelis L. et al. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder: Case report and literature review. J Gastrointest Cancer 2012; 43 Suppl 1: S139-44

- Su JS, Chen YT, Wang RC, Wu CY, Lee SW, Lee TY. Clinicopathological characteristics in the differential diagnosis of hepatoid adenocarcinoma: A literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19: 321-7

- Jo JM, Kim JW, Heo SH, Shin SS, Jeong YY, Hur YH. Hepatic metastases from hepatoid adenocarcinoma of stomach mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Mol Hepatol 2012; 18: 420-3

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share