“PALLCARE Seva”—A Beacon Amid the Catastrophic COVID-19 Times: A Cross-Sectional Study from a Rural Oncology Institute in Western Maharashtra

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2022; 43(04): 369-375

DOI: DOI: 10.1055/s-0042-1754371

Abstract

Introduction Advanced cancer patients often require clinic or hospital follow-up for their symptom control to maintain their quality of life. But it becomes difficult for the patients to attend the same due to financial, commutation, and logistic issues.

Objective The aim of this study was to audit the telephonic calls of the service and prospectively collected data to understand the quality of service provided to the patients at follow-up.

Materials and Methods An ambispective observational study was conducted on the advanced stage cancer patients referred to the palliative care department at Kolhapur Cancer Center, Kolhapur, Maharashtra. We conducted an audit of the 523 telephonic calls of our service—“PALLCARE Seva” from June 2020 to February 2021. Prospectively, we assessed the quality of service based on 125 telephonic calls (n = 125) for this; we designed a questionnaire consisting of 11 items on the 5-point Likert scale for satisfaction by the patients or their caregivers at the follow-up. After a pilot study, the final format of questionnaire was used to collect the data.

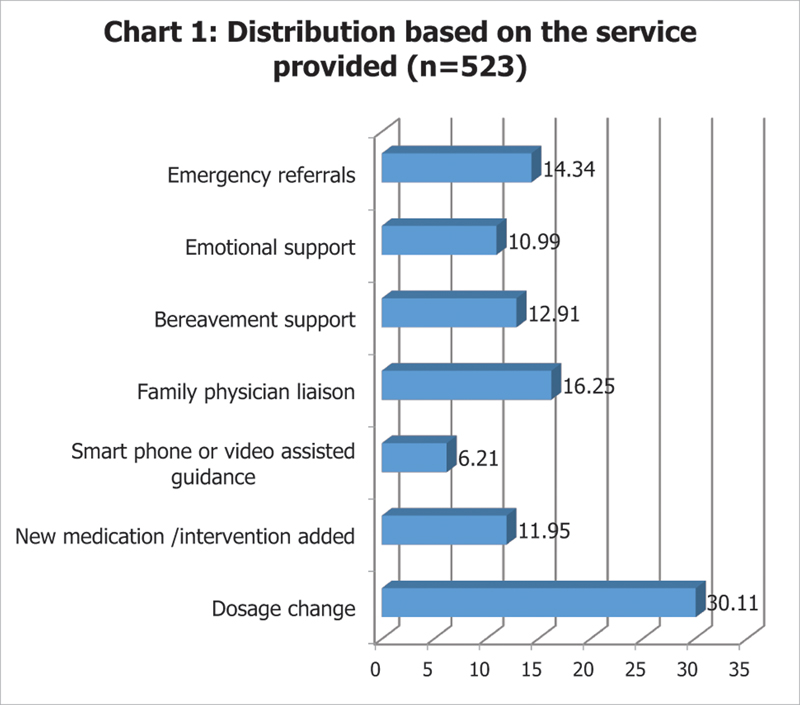

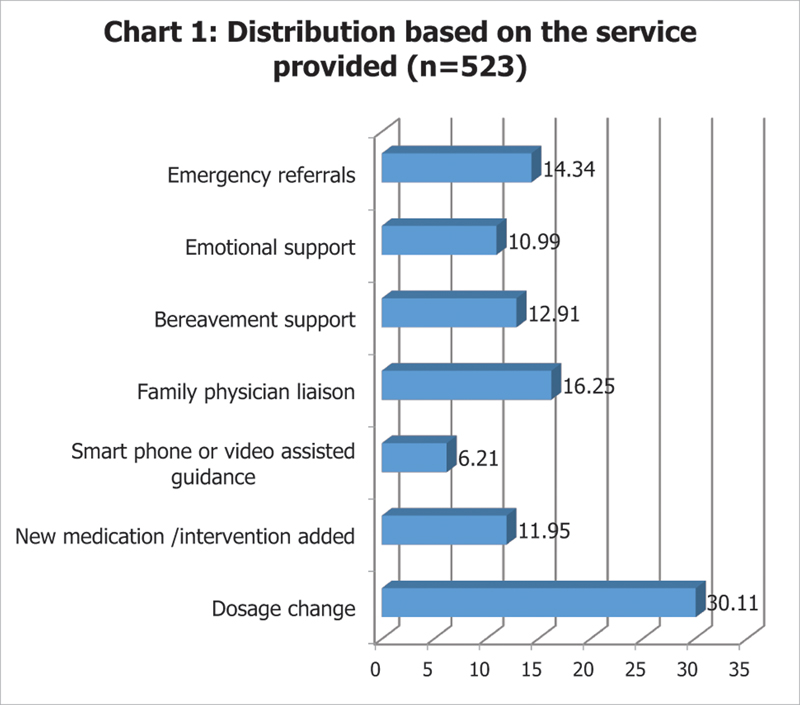

Results Of the 523 calls attended, we provided 30.11% patients with dosage change of medications for their symptom management, 16.25% patients have liaised with local general practitioners, and 14.34% of cases had to be referred for emergency management to our hospitals. We provided 23.9% of them with emotional and bereavement support and 6.21% with smartphone-based or video-assisted guidance to the patients and caregivers.

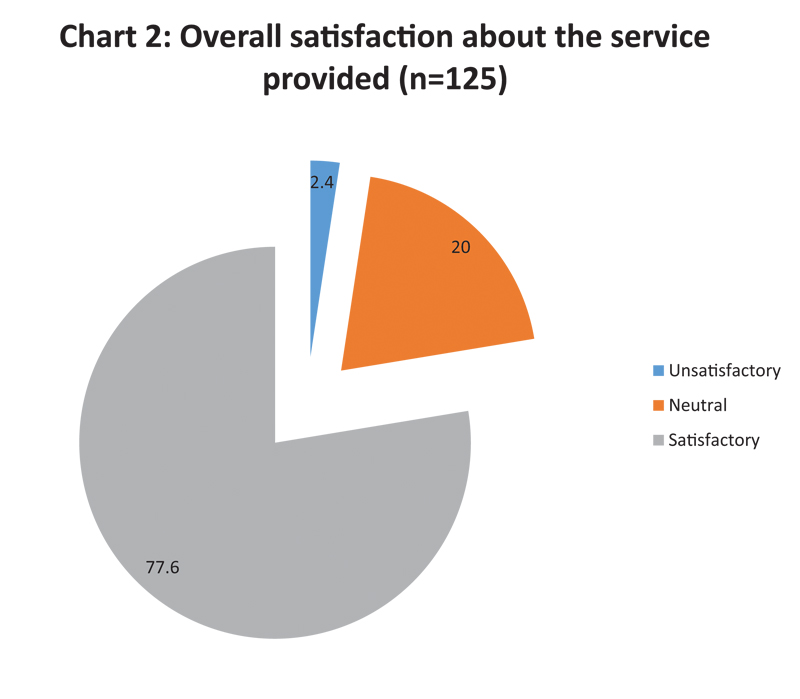

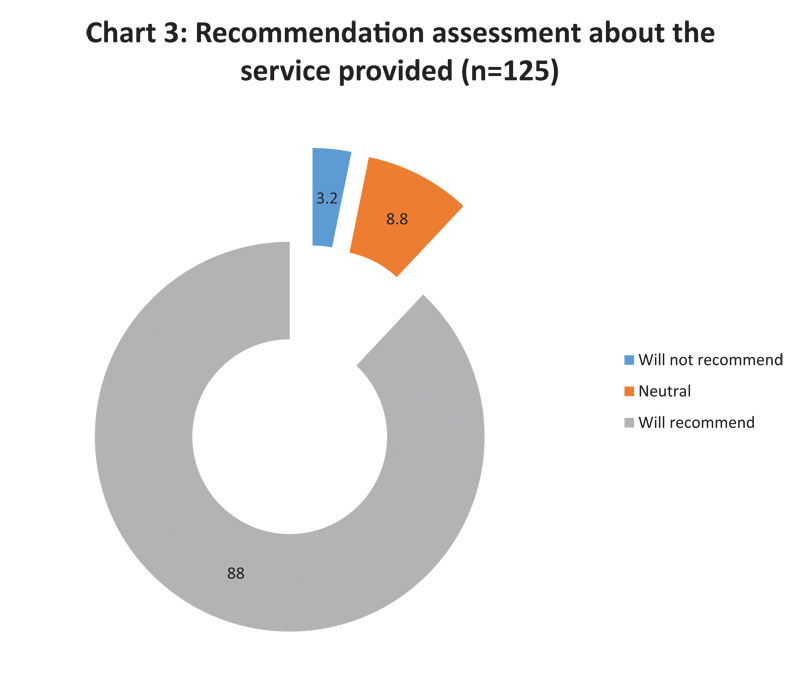

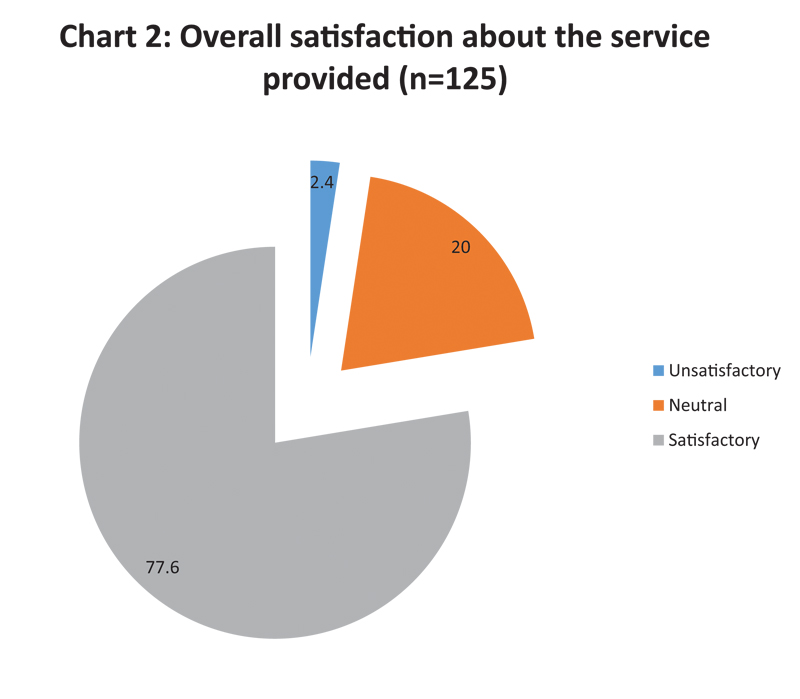

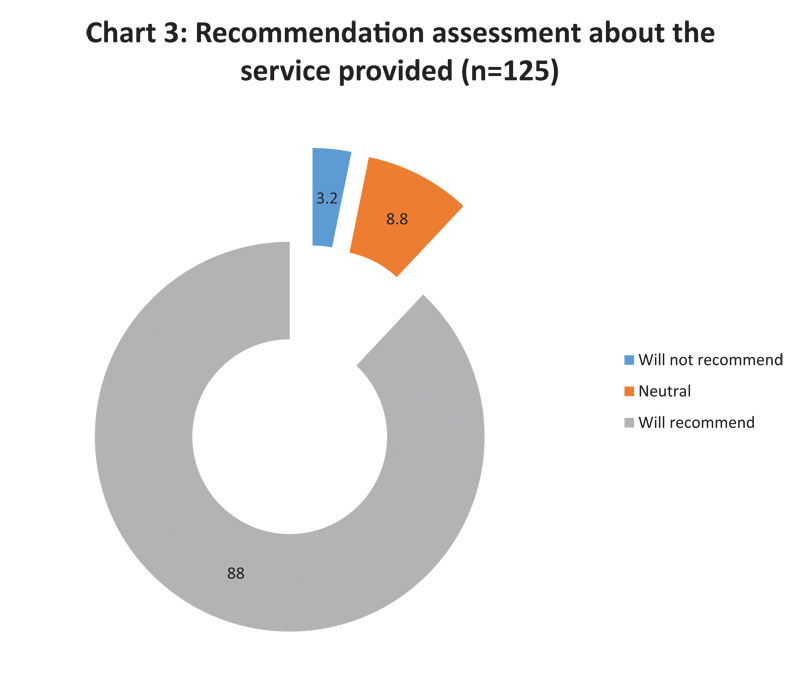

Conclusions Liaison of general practitioners was possible in more than one-tenth of cases. The core components of our service were politeness and caring attitude, helpfulness, handling doubts regarding the illness, and an opportunity to share thoughts from the patients or caregivers. More than three-fourth of the callers have rated their experience as satisfactory and would recommend this service to other patients in need.

Publication History

Article published online:

01 September 2022

© 2022. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Introduction Advanced cancer patients often require clinic or hospital follow-up for their symptom control to maintain their quality of life. But it becomes difficult for the patients to attend the same due to financial, commutation, and logistic issues.

Objective The aim of this study was to audit the telephonic calls of the service and prospectively collected data to understand the quality of service provided to the patients at follow-up.

Materials and Methods An ambispective observational study was conducted on the advanced stage cancer patients referred to the palliative care department at Kolhapur Cancer Center, Kolhapur, Maharashtra. We conducted an audit of the 523 telephonic calls of our service—“PALLCARE Seva” from June 2020 to February 2021. Prospectively, we assessed the quality of service based on 125 telephonic calls (n = 125) for this; we designed a questionnaire consisting of 11 items on the 5-point Likert scale for satisfaction by the patients or their caregivers at the follow-up. After a pilot study, the final format of questionnaire was used to collect the data.

Results Of the 523 calls attended, we provided 30.11% patients with dosage change of medications for their symptom management, 16.25% patients have liaised with local general practitioners, and 14.34% of cases had to be referred for emergency management to our hospitals. We provided 23.9% of them with emotional and bereavement support and 6.21% with smartphone-based or video-assisted guidance to the patients and caregivers.

Conclusions Liaison of general practitioners was possible in more than one-tenth of cases. The core components of our service were politeness and caring attitude, helpfulness, handling doubts regarding the illness, and an opportunity to share thoughts from the patients or caregivers. More than three-fourth of the callers have rated their experience as satisfactory and would recommend this service to other patients in need.

Introduction

Within a short period, the pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) emerged to become a public health emergency of international concern.[1] As with other healthcare services, routine oncological practices were also affected.[2] Cancer patients per se have a higher risk of contracting COVID-19 infection and are associated with a poorer prognosis if contracted.[3] [4] [5] [6] Delay in cancer resection surgeries, neoadjuvant therapy, radiation therapy, and palliative care services had started affecting the quality of life of the cancer patients.[7] [8] With the progression of the pandemic, an urgent need for modification in the routine practice was required. The government of India suggested telemedicine as the mode to provide equitable care to the patients.[9] But, there were some practical challenges like the lack of interaction between doctor and patient, accessibility issues, regional effects, care delays, technical issues, and licensing issues associated with it.[10] [11] [12] [13] Amid all these challenges, it was important that patient-centered services had to be provided. So, we started a telemedicine support service called “PALLCARE Seva” for our patients.

With regard to this pandemic situation, a quality palliative care service is the one that can maintain the continuum of care throughout the illness trajectory of the cancer patient.[14] [15] [16] Most advanced cancer patients prefer to be taken care of and die at home with family members. Advanced cancer patients often require clinic or hospital follow-up for their symptom control to maintain their quality of life.[17] [18] But, it becomes difficult for the patients to attend the same due to financial, and logistic issues.[19] [20] [21] With this background, we conducted this study intending to audit the telephonic calls of the service and prospectively collected data to understand the quality of service provided to the patients during the follow-up.

Materials and Methods

An ambispective observational study was conducted on the advanced stage cancer patients referred to the palliative care department at Kolhapur Cancer Center, Kolhapur, Maharashtra. It was a retrospective audit of our service “PALLCARE Seva.” PALLCARE Seva is a proactive telephonic follow-up and consultation service. The patients who consulted the palliative care physician during the week (Monday to Friday) were called on Saturday by trained personnel to inquire about the improvement in symptoms, new symptoms, and any other issues. This telephonic service line was kept open from 9 am to 6 pm on all days except for Sundays. This available line served as an assistant to the patients if they needed any help. A specialist palliative care physician supervised the whole program. Those patients who needed care were requested to involve their local physicians for any assistance. We also provided telephonic guidance for local physicians. The main motto was to provide “right care at the right time.” Primary outcome measures were demographic distribution of our calls and quality of service.

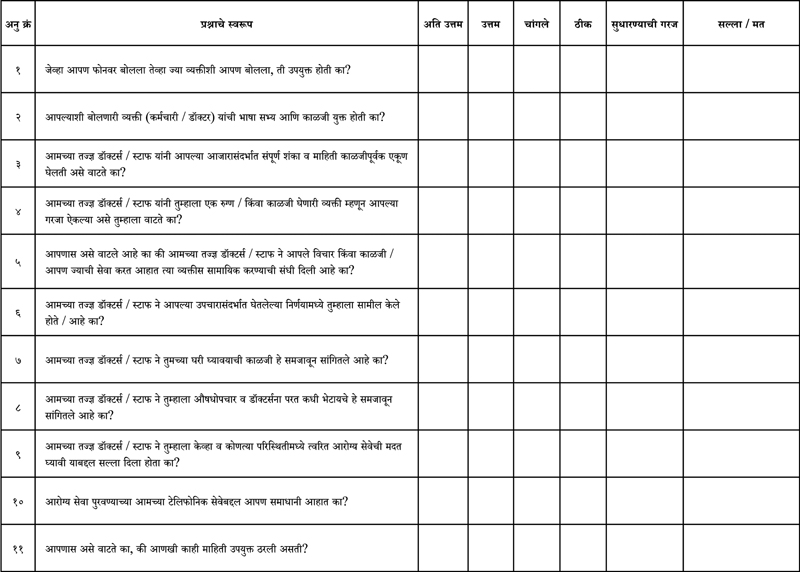

An audit of the telephonic calls is from June 2020 to February 2021 was conducted. We noted age, gender, area of residence, type of calls, the caller's relationship with the patient, and the site of cancer. In addition, we noted services like dosage change, medication-related queries, emergency referrals, emotional support, bereavement support, liaison with general practitioners, and smartphone-assisted guidance. Prospectively, we assessed the quality of service. For evaluating the quality of service we provided, we designed a questionnaire consisting of 11 items (Annexure 1). The items were related to helpfulness, politeness and caring attitude, handling doubts and information regarding the illness, patient listening to personnel, opportunity to share patient's thoughts, involvement in decision making, explanation of care, explanation about medication, and circumstances seeking emergency help and its mode. The last two items were related to their overall satisfaction level of the service and recommendation of this service to other patients. All these questions were rated based on the “5-point Likert scale” for satisfaction by the patients or their caregivers at the follow-up. This questionnaire was designed by experts in palliative care and quality. Originally written in English, this questionnaire was converted to Marathi (local language) by a team of expert translators. It was back-translated and tested on ten caregivers, and we did final modifications.

Our study population consisted of advanced stage cancer patients seeking palliative care and patients referred for pain and symptom management by various departments within the institute. Of the total 630 calls done throughout 8 months, we excluded 107. The main reasons for exclusion were connection-related issues and nonreceiving of calls from the recipient. Hence, the final sample size included in this study consisted of 523 calls. Assuming the overall quality of service to be good in 50% of the feedbacks, with 10%-absolute error and 95%-confidence interval, we found the minimum sample size to be 96. Considering the attrition rate of 30%, we found the final sample size to be 124. But we collected 125 feedbacks about this service. For analysis, the 5-point Likert scale was categorized into unsatisfactory, satisfactory, and neutral. All the data collection and phone calls were done by trained personnel under the supervision of the palliative care physicians.

To reduce the recall bias during the feedback, the interval between the last call and follow-up was kept to a minimum. Since the prospective feedback was collected from the caregiver or the patient in random selection, the selection bias was reduced to the minimum possible extent.

Statistical Analysis

The data was collected and compiled using Microsoft Excel. The analysis was done using Epi info (Version 7.2; CDC, Atlanta, Georgia, United States). The qualitative variables were expressed in terms of frequencies and percentages.

Ethics

For the prospective quality feedback of the service, we took a written informed consent form from the person who responded (either the caregiver or the patient). We sought permission of the ethical committee of Kolhapur Cancer Center before the start of the study (ECR/523/ Inst/ MH/ 2014/ RR-20).

We ensured the anonymity of the participants with their due permission.

Results

We have included 523 telephonic calls in this study.

The majority of the callers were in the age group of 40 to 60 years and of the male gender. Since the center caters to majority of rural areas of the district, 53.15%-were from rural areas. About 72.28%-of the cases were outgoing calls. Head, face, and neck cancers were the most common cancers reported ([Table 1]).

|

Demographic characteristics |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|---|---|---|

|

Age group |

||

|

< 20 |

16 |

3.05 |

|

21 to 40 |

105 |

20.00 |

|

40 to 60 |

212 |

40.53 |

|

> 60 |

190 |

36.33 |

|

Gender |

||

|

Female |

203 |

38.88 |

|

Male |

320 |

61.21 |

|

Relationship with the patient |

||

|

Brother/sister |

144 |

27.53 |

|

Parents |

16 |

3.05 |

|

Children |

129 |

24.67 |

|

Spouse |

234 |

44.75 |

|

Area of residence |

||

|

Rural |

278 |

53.15 |

|

Urban |

245 |

46.85 |

|

Type of call |

||

|

Incoming |

145 |

27.72 |

|

Outgoing |

378 |

72.28 |

|

Site of cancer |

||

|

Head, face and Neck |

276 |

52.77 |

|

Thorax |

42 |

8.03 |

|

Gastrointestinal |

101 |

19.31 |

|

Genitourinary |

62 |

11.85 |

|

Others |

42 |

8.03 |

| Figure 1:Distribution based on the service provided (n = 523).

Politeness and caring attitude (91.20%), helpfulness (88.00%), handling doubts and information regarding the illness (88.00%), and opportunity to share thoughts (88%) were the most satisfying elements of our service and personnel ([Table 2]).

|

Questions |

Unsatisfactory |

Neutral |

Satisfactory |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number |

% |

Number |

% |

Number |

% |

|

|

1. Helpfulness |

4 |

3.20 |

11 |

8.80 |

110 |

88.00 |

|

2. Politeness and caring attitude |

3 |

2.40 |

8 |

6.40 |

114 |

91.20 |

|

3. Handling doubts and information regarding illness |

5 |

4.00 |

10 |

8.00 |

110 |

88.00 |

|

4. Patient listening |

6 |

4.80 |

12 |

9.60 |

107 |

85.60 |

|

5. Opportunity to share thoughts |

6 |

4.80 |

9 |

7.20 |

110 |

88.00 |

|

6. Involvement in decision making process |

6 |

4.80 |

11 |

8.80 |

108 |

86.40 |

|

7. Explanation of care |

5 |

4.00 |

32 |

25.60 |

88 |

70.40 |

|

8. Explanation about medication |

5 |

4.00 |

26 |

20.80 |

94 |

75.20 |

|

9. Explanation about circumstances seeking help and its mode |

4 |

3.20 |

14 |

11.20 |

107 |

85.60 |

| Figure 2:Overall satisfaction about the service provided (n = 125) (%).

About 88.00% (n = 110) of the patients would recommend the service to other patients who require similar type of assistance ([Fig. 3]).

| Figure 3:Recommendation assessment about the service provided (n= 125) (%).

Discussion

Telemedicine has become an essential component of the present oncology care worldwide due to the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic.[11] This “no contact” approach had to be inculcated into the guidelines of routine practice in oncological care to break the barrier of transmission of this deadly infection.[12] With this view, we decided to maintain the quality of care for our advanced stage cancer patients to the next level with the help of consultations and started the same over the phone. The basic principles of a palliative care support helpline are direct communication between palliative care physicians with the family; staffing expansion along with training; call line supporting clinicians, families, and the patients; monitoring of call volume throughout the week; and being an ideal choice for crisis response. We started our service with these basic principles, but, unfortunately, due to limited resources, we opened the call line only during the outpatient consultation hours (2 pm to 6 pm). Based on the interim audit of these calls (2 months), we decided to open this line from 9 am to 6 pm with adequate staff training and tele-help support for any crisis.

Change of dosage of the medications for pain and other symptom management was most commonly encountered over these telephonic calls. The results of our study were similar to a survey conducted by Adhikari et al.[22] This study unfolded their experience of telemedicine consultations of their institution. Majority of the calls (63.62%) were related to uncontrolled symptoms experienced by the patients. Similar study findings have been reported by Jiang et al[23] and Plummer and Allan.[24] Due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, patients could not visit in person for any minor symptom management. So, this service helped the advanced stage cancer patients in this regard.

In 16.25%-of the cases, we could liaise with the family physicians and handle the patient's issues. These findings were similar to the integrated model postulated by Atreya et al[25] in their study. Despite the pandemic situation, these family physicians worked relentlessly to assist in caring for these patients. Starting from management of minor ailments with injectable medication to terminal care of these patients with appropriate help by the specialist palliative care physician over the phone. The family physicians were vigilant in managing the symptoms, and in case of crisis, they did emergency referrals to our institute for further management. Emergency referral cases usually involved uncontrolled severe pain despite providing essential medications. These cases also suffer from spinal cord compression, intestinal obstruction, abnormalities in levels of electrolytes, and convulsions. It is imperative to integrate these family physicians into the training of palliative care to strengthen this service in the future. One of the crucial recommendations is the joint statement of the Indian Association of Palliative Care and the Academy of Family Physicians of India to integrate palliative care at all levels of healthcare and liaise with general practitioners and family physicians.[26]

Bereavement support is one of the crucial components of palliative care service. In approximately 12.95%-of cases, we provided this support over the phone. In cases with crises such as death of patients causing grief in caregivers or a medical condition hindering the caregiver's health, we offered the best possible support through the specialists over the phone. A retrospective study conducted on the out-of-hours phone calls by Jiang et al[23] reported that 17.8%-cases mentioned distress due to the death of the patient over telephonic support and here bereavement support was provided. Emotional support to the patients and their caregivers was provided by letting them ventilate and express their concerns in 10.99% of cases. Mandal [27] described that their telephonic service provided had advantages of providing regular physical and emotional support, reducing problems regarding finance and human resources, and thus improving their quality of life. Jiang et al[23] reported that in 3.5%-of their patients, they could provide emotional support over the phone.

As a part of clinical governance, we took feedback from a small sample (n = 125) of the patient or caregivers who visited us during follow-ups. We found that politeness and caring attitude (91.20%), helpfulness (88.00%), handling doubts and information regarding the illness (88.00%), and opportunity to share thoughts (88%) were the most satisfying elements of our service and service personnel. Further, approximately 77.40%-of the patients were satisfied with the service provided, and 88%-reported that they would recommend it to other patients in need. Similar feedbacks were taken by Adhikari et al[22] in their study and found that more than 70%-of their patients were satisfactory about the telehealth service provided. Compared with their research, we used video consultations (6.12%) in a minor set of patients due to logistic issues. Also, Plummer and Allan[24] reported that 66%-of patients claimed to have a high satisfaction rate.

This study had some limitations. First, even though it was a retrospective study, we took the necessary feedback through follow-ups prospectively in our research. Due to issues regarding logistics and loss of follow-up of the patients, we could only obtain and analyze a subset of the original sample size. The second limitation was that the study design was of observational type. Feedback, complaint redressal, and feedback mechanisms must be set as a quality control check in such services. Future studies should target integrating general practitioners and family physicians into palliative care, education of informal caregivers about the management of minor ailments, etc. The cost-effectiveness of such services has to be evaluated in the future.

Conclusion

Change in dosage and addition of new medication were the most common issues handled over the phone. Liaison of general practitioners was possible in more than one-tenth of cases. We successfully provided both bereavement and emotional support for the patients and their caregivers whenever appropriate. We could also use newer technologies such as video consultation and smartphone-based assistance for patient care in a few cases. The core components of our service were politeness and caring attitude, helpfulness, handling doubts regarding the illness, and an opportunity to share thoughts with the patients or caregivers. More than three-fourth of the patients were satisfactory and would recommend this service to other patients in need.

Audit: (To be filled by the in charge person of the calls)

Patient's details:

Age:

Gender: Male/Female

Residence:

Phone number:

Type of calls: incoming/outgoing

Caller's relationship with the patients:

Site of cancer:

Quality of service provided by us during telephonic consultation (Patient/ caregiver feedback)

Marathi version of the questions for feedback of the service:

|

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Wilder-Smith A, Osman S. Public health emergencies of international concern: a historic overview. J Travel Med 2020; 27 (08) taaa227

- Kumar A, Rajasekharan Nayar K, Koya SF. COVID-19: challenges and its consequences for rural health care in India. Public Health Pract (Oxf) 2020; 1: 100009

- ElGohary GM, Hashmi S, Styczynski J. et al. The risk and prognosis of COVID-19 infection in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther 2020:S1658-3876(20)30122-9

- Curigliano G. Cancer patients and risk of mortality for COVID-19. Cancer Cell 2020; 38 (02) 161-163

- Al-Quteimat OM, Amer AM. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer patients. Am J Clin Oncol 2020; 43 (06) 452-455

- Yang L, Chai P, Yu J, Fan X. Effects of cancer on patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 63,019 participants. Cancer Biol Med 2021; 18 (01) 298-307

- Gosain R, Abdou Y, Singh A, Rana N, Puzanov I, Ernstoff MS. COVID-19 and cancer: a comprehensive review. Curr Oncol Rep 2020; 22 (05) 53

- Palka-Kotlowska M, Custodio-Cabello S, Oliveros-Acebes E, Khosravi-Shahi P, Cabezón-Gutierrez L. Review of risk of COVID-19 in cancer patients and their cohabitants. Int J Infect Dis 2021; 105: 15-20

- Mohfw.. gov [Internet]. Telemedicine Practice Guidelines. [Updated Apr 2020; Cited Jan 2021]. Accessed July 12, 2022 from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/Telemedicine.pdf

- Kichloo A, Albosta M, Dettloff K. et al. Telemedicine, the current COVID-19 pandemic and the future: a narrative review and perspectives moving forward in the USA. Fam Med Community Health 2020; 8 (03) e000530

- Scott Kruse C, Karem P, Shifflett K, Vegi L, Ravi K, Brooks M. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare 2018; 24 (01) 4-12

- Giani E, Laffel L. Opportunities and challenges of telemedicine: observations from the wild west in pediatric type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2016; 18 (01) 1-3

- Seto E, Smith D, Jacques M, Morita PP. Opportunities and challenges of telehealth in remote communities: case study of the Yukon telehealth system. JMIR Med Inform 2019; 7 (04) e11353-e11353

- Al-Mahrezi A, Al-Mandhari Z. Palliative care: time for action. Oman Med J 2016; 31 (03) 161-163

- Cruz-Oliver DM. Palliative care: an update. Mo Med 2017; 114 (02) 110-115

- García-Baquero Merino MT. Palliative care: taking the long view. Front Pharmacol 2018; 9: 1140

- Jabbarian LJ, Maciejewski RC, Maciejewski PK. et al. The stability of treatment preferences among patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019; 57 (06) 1071-1079.e1

- Umezawa S, Fujimori M, Matsushima E, Kinoshita H, Uchitomi Y. Preferences of advanced cancer patients for communication on anticancer treatment cessation and the transition to palliative care. Cancer 2015; 121 (23) 4240-4249

- Pai RR, Nayak MG, Sangeetha N. Palliative care challenges and strategies for the management amid COVID-19 pandemic in India: perspectives of palliative care nurses, cancer patients, and caregivers. Indian J Palliat Care 2020; 26 (Suppl. 01) S121-S125

- Abu-Odah H, Molassiotis A, Liu J. Challenges on the provision of palliative care for patients with cancer in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of reviews. BMC Palliat Care 2020; 19 (01) 55

- Woo JA, Maytal G, Stern TA. Clinical challenges to the delivery of end-of-life care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 8 (06) 367-372

- Adhikari SD, Biswas S, Mishra S. et al. Telemedicine as an acceptable model of care in advanced stage cancer patients in the era of coronavirus disease 2019 - an observational study in a tertiary care centre. Indian J Palliat Care 2021; 27 (02) 306-312

- Jiang Y, Gentry AL, Pusateri M, Courtney KL. A descriptive, retrospective study of after-hours calls in hospice and palliative care. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2012; 14 (05) 343-350

- Plummer S, Allan R. Analysis of a network-wide specialist palliative care out-of-hours advice and support line: a model for the future. Int J Palliat Nurs 2011; 17 (10) 494-499

- Atreya S, Patil C, Kumar R. Integrated primary palliative care model; facilitators and challenges of primary care/family physicians providing community-based palliative care. J Family Med Prim Care 2019; 8 (09) 2877-2881

- Jeba J, Atreya S, Chakraborty S. et al. Joint position statement Indian Association of Palliative Care and Academy of Family Physicians of India - the way forward for developing community-based palliative care program throughout India: policy, education, and service delivery considerations. J Family Med Prim Care 2018; 7 (02) 291-302

- Mandal N. Telephonic communication in palliative care for better management of terminal cancer patients in rural India: an NGO-based approach. Ann Oncol 2019; 30 (November): ix144-ix145

Address for correspondence

Publication History

Article published online:

01 September 2022

© 2022. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

| Figure 1:Distribution based on the service provided (n = 523).

| Figure 2:Overall satisfaction about the service provided (n = 125) (%).

| Figure 3:Recommendation assessment about the service provided (n= 125) (%).

References

- Wilder-Smith A, Osman S. Public health emergencies of international concern: a historic overview. J Travel Med 2020; 27 (08) taaa227

- Kumar A, Rajasekharan Nayar K, Koya SF. COVID-19: challenges and its consequences for rural health care in India. Public Health Pract (Oxf) 2020; 1: 100009

- ElGohary GM, Hashmi S, Styczynski J. et al. The risk and prognosis of COVID-19 infection in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther 2020:S1658-3876(20)30122-9

- Curigliano G. Cancer patients and risk of mortality for COVID-19. Cancer Cell 2020; 38 (02) 161-163

- Al-Quteimat OM, Amer AM. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer patients. Am J Clin Oncol 2020; 43 (06) 452-455

- Yang L, Chai P, Yu J, Fan X. Effects of cancer on patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 63,019 participants. Cancer Biol Med 2021; 18 (01) 298-307

- Gosain R, Abdou Y, Singh A, Rana N, Puzanov I, Ernstoff MS. COVID-19 and cancer: a comprehensive review. Curr Oncol Rep 2020; 22 (05) 53

- Palka-Kotlowska M, Custodio-Cabello S, Oliveros-Acebes E, Khosravi-Shahi P, Cabezón-Gutierrez L. Review of risk of COVID-19 in cancer patients and their cohabitants. Int J Infect Dis 2021; 105: 15-20

- Mohfw.. gov [Internet]. Telemedicine Practice Guidelines. [Updated Apr 2020; Cited Jan 2021]. Accessed July 12, 2022 from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/Telemedicine.pdf

- Kichloo A, Albosta M, Dettloff K. et al. Telemedicine, the current COVID-19 pandemic and the future: a narrative review and perspectives moving forward in the USA. Fam Med Community Health 2020; 8 (03) e000530

- Scott Kruse C, Karem P, Shifflett K, Vegi L, Ravi K, Brooks M. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare 2018; 24 (01) 4-12

- Giani E, Laffel L. Opportunities and challenges of telemedicine: observations from the wild west in pediatric type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2016; 18 (01) 1-3

- Seto E, Smith D, Jacques M, Morita PP. Opportunities and challenges of telehealth in remote communities: case study of the Yukon telehealth system. JMIR Med Inform 2019; 7 (04) e11353-e11353

- Al-Mahrezi A, Al-Mandhari Z. Palliative care: time for action. Oman Med J 2016; 31 (03) 161-163

- Cruz-Oliver DM. Palliative care: an update. Mo Med 2017; 114 (02) 110-115

- García-Baquero Merino MT. Palliative care: taking the long view. Front Pharmacol 2018; 9: 1140

- Jabbarian LJ, Maciejewski RC, Maciejewski PK. et al. The stability of treatment preferences among patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019; 57 (06) 1071-1079.e1

- Umezawa S, Fujimori M, Matsushima E, Kinoshita H, Uchitomi Y. Preferences of advanced cancer patients for communication on anticancer treatment cessation and the transition to palliative care. Cancer 2015; 121 (23) 4240-4249

- Pai RR, Nayak MG, Sangeetha N. Palliative care challenges and strategies for the management amid COVID-19 pandemic in India: perspectives of palliative care nurses, cancer patients, and caregivers. Indian J Palliat Care 2020; 26 (Suppl. 01) S121-S125

- Abu-Odah H, Molassiotis A, Liu J. Challenges on the provision of palliative care for patients with cancer in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of reviews. BMC Palliat Care 2020; 19 (01) 55

- Woo JA, Maytal G, Stern TA. Clinical challenges to the delivery of end-of-life care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 8 (06) 367-372

- Adhikari SD, Biswas S, Mishra S. et al. Telemedicine as an acceptable model of care in advanced stage cancer patients in the era of coronavirus disease 2019 - an observational study in a tertiary care centre. Indian J Palliat Care 2021; 27 (02) 306-312

- Jiang Y, Gentry AL, Pusateri M, Courtney KL. A descriptive, retrospective study of after-hours calls in hospice and palliative care. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2012; 14 (05) 343-350

- Plummer S, Allan R. Analysis of a network-wide specialist palliative care out-of-hours advice and support line: a model for the future. Int J Palliat Nurs 2011; 17 (10) 494-499

- Atreya S, Patil C, Kumar R. Integrated primary palliative care model; facilitators and challenges of primary care/family physicians providing community-based palliative care. J Family Med Prim Care 2019; 8 (09) 2877-2881

- Jeba J, Atreya S, Chakraborty S. et al. Joint position statement Indian Association of Palliative Care and Academy of Family Physicians of India - the way forward for developing community-based palliative care program throughout India: policy, education, and service delivery considerations. J Family Med Prim Care 2018; 7 (02) 291-302

- Mandal N. Telephonic communication in palliative care for better management of terminal cancer patients in rural India: an NGO-based approach. Ann Oncol 2019; 30 (November): ix144-ix145

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share