Ovarian Torsion as an Unusual Presentation of Primary Bilateral Ovarian Lymphoma

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2018; 39(01): 88-90

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/ijmpo.ijmpo_68_17

Abstract

Primary ovarian involvement by Burkitt's lymphoma is rare and accounts for 0.5% of nonHodgkin lymphoma and 1.5% of ovarian tumors. We herein describe a very rare case of primary bilateral ovarian lymphoma in a 14-year-old presenting as ovarian torsion.

Keywords

Burkitt - non-Hodgkin lymphoma - ovarian lymphoma - torsion

Publication History

23 June 2021

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Primary ovarian involvement by Burkitt's lymphoma is rare and accounts for 0.5% of nonHodgkin lymphoma and 1.5% of ovarian tumors. We herein describe a very rare case of primary bilateral ovarian lymphoma in a 14-year-old presenting as ovarian torsion.

Keywords

Burkitt - non-Hodgkin lymphoma - ovarian lymphoma - torsion

Introduction

Burkitt's lymphoma (BL) is a highly aggressive form of B-cell nonHodgkin lymphoma (NHL) that occurs in children and young adults. While secondary ovarian involvement is common with reported incidence as high as 26%, the primary ovarian lymphoma is rare with an incidence of 0.5% of NHL and 1.5% of ovarian tumors.[1],[2] This is due to the absence of lymphoid tissue within the ovary.[3] The presentation of ovarian lymphoma is often nonspecific with patient often presenting with ovarian mass and chronic symptoms such as pelvic pain, abnormal vaginal bleeding, bowel, and bladder symptoms. Here, we report a very rare case of primary bilateral ovarian lymphoma presenting as ovarian torsion.

Case Report

A 14-year-old girl presented to the emergency room for the evaluation of right lower quadrant abdominal pain. She reported few episodes of similar pain in the past but noted this to be more intense. She denied fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, dyspnea, chest pain, dysuria, and gastrointestinal symptoms. Patient also reported irregular menstrual cycles for which she was using oral contraceptive medication. Her last menstrual cycle was 2 months back. She denied any sexual activity and her past medical history was otherwise unremarkable. The general systemic examination was normal. On vaginal examination, a small firm and tender mass was felt in the right adnexa. Routine hematological and biochemical investigations were normal.

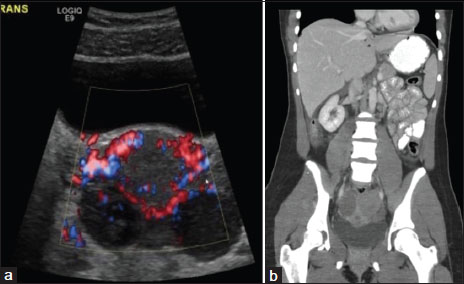

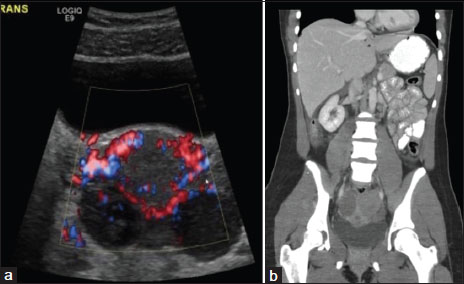

An ovarian torsion was suspected, but transvaginal ultrasound performed in the emergency room demonstrated enlargement of both the ovaries. The ovaries were hypoechoic without posterior acoustic enhancement. Doppler examination revealed decreased flow in the ovaries [Figure 1]a. A computer tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen revealed solid masses replacing both the ovaries with decreased attenuation of the right ovarian mass [Figure 1]b. An enlarged left para aortic lymph node was also present. There was no free fluid in the abdominal cavity. A presumptive diagnosis of bilateral ovarian neoplasm with possible torsion of the right ovary was made. The patient was consented for an emergent exploratory laparotomy. However, it was deferred as the patient started showing symptomatic improvement. A surgical exploration was planned following further staging investigations.

| Figure.1(a) Color Doppler ultrasound of the pelvis demonstated hypoechoic enlargement of both ovaries with reduced flow. (b) Coronal computer tomography scan of the abdomen revealed solid masses replacing both the ovaries with decreased attenuation of the right ovarian mass

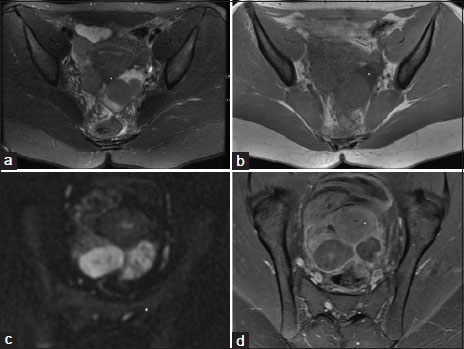

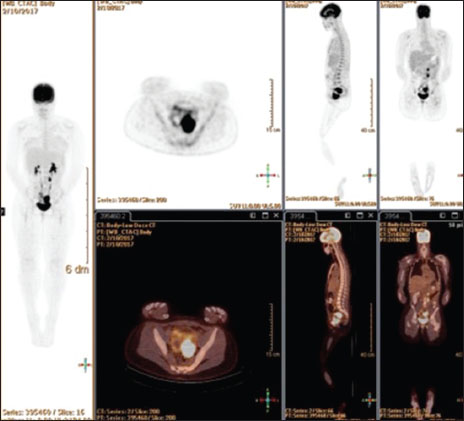

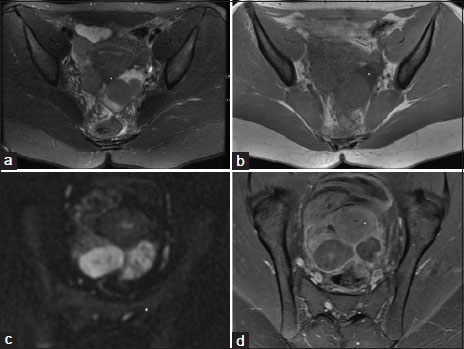

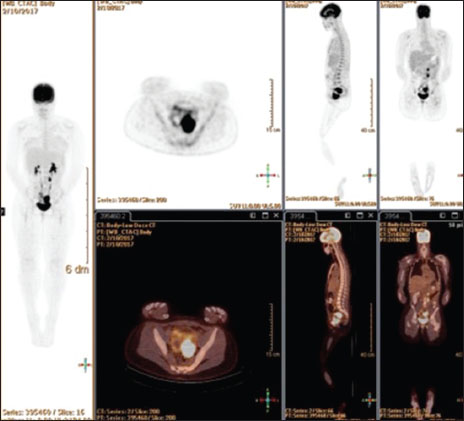

The patient was transferred to the gynecological oncology service for further work-up of a suspected ovarian neoplasm. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis demonstrated bilateral ovarian masses abutting the uterine fundus, which were hypointense on T1-weighted image and hyperintense on T2-weighted image. The lesions demonstrated heterogonous enhancement and diffusion restriction [Figure 2]. A whole body positron emission tomography CT was performed for staging revealed uptake in both ovaries and left paraaortic lymph node [Figure 3]. No additional site of disease was identified. Further investigation showed only CA-125 to be mildly elevated among the tumor markers that were checked.

| Figure.2Magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis demonstrated bilateral ovarian masses abutting the uterine fundus, which were hyperintense on T2-weighted image (a) and hypointense on T1-weighted image (b). The lesions demonstrated restriction on diffusion-weighted imaging (c) and heterogonous enhancement on postcontrast sequence (d)

| Figure.3A whole body positron emission tomography computed tomography was performed for staging revealed uptake in both ovaries and left paraaortic lymph node

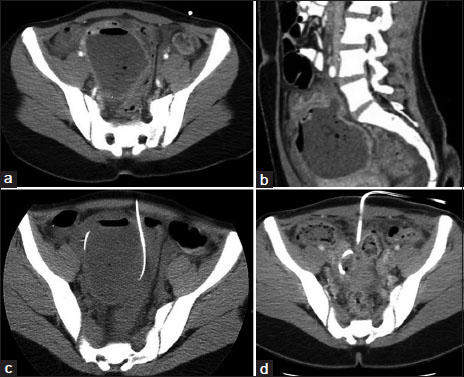

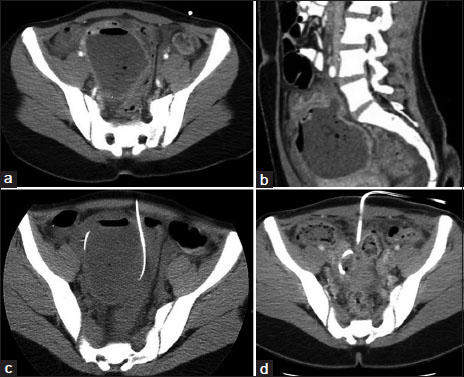

The patient underwent a diagnostic laparoscopy with pelvic washings, adhesiolysis, and right ovarian and peritoneal biopsy. The postoperative course was complicated by pelvic abscess and wound infection [Figure 4]a and [Figure 4]b. This was managed by percutaneous drainage of the abscess by interventional radiology along with antibiotics [Figure 4]c and [Figure 4]d. She recovered well to a stable condition. Her pathology came back positive for high-grade B cell lymphoma (BCL) with identification of MYC gene rearrangement in the absence of the BCL2 and BCL6 gene rearrangements, consistent with immune profile of Burkitt lymphoma. Bone marrow and peripheral blood examination were negative for lymphoma. No malignant cell was detected in cerebrospinal fluid.

| Figure.3(a and b) Axial and sagittal postoperative computer tomography scan of the abdomen demonstrated pelvic abscess. (c and d) The abscess was drained under computed tomography guidance

The patient was treated with according to the ANHL1131 trial protocol using COP-R regimen comprising of cyclophosphamide, oncovin, prednisone with rituximab. The tumor reduced significantly in size over the next 2-months. The patient is on 3 months follow-up, which is uneventful.

Discussion

BL was first described by Dr. Parsons in children of Africa.[4] BL is a highly undifferentiated B-cell NHL that shows an extremely rapid growth rate with a doubling time as short as 24 h.[5] BL mainly affects children but can occur in adults also. The histologic hallmark of BL is a monomorphic proliferation of medium sized lymphoma cells that express surface immunoglobulin M- and B-cell associated antigens (CD19, CD20) with rearrangement involving the c-MYC oncogene on genetic analysis.[6]

The World Health Organization classification in 2008 recognizes three clinical subtypes of BL: endemic, sporadic, and immunodeficiency associated.[7]

Although they have the same histology, each form has distinct epidemiology and clinical presentation. The endemic or African form presents as tumors of the jaw or facial bones with frequent involvement of kidneys. Immunodeficiency-associated BL involves lymph node involvement and is common in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. On the other hand, sporadic BL presents with abdominal masses involving different organs. Ebstein Barr virus is strongly associated with endemic BL, but it can also be detected in up to 20 ses of sporadic BL samples.[5]

Each form of BL can spread to extranodal sites including the ovary, testis, kidney, mesentery, bowel, breast, bone marrow, and central nervous system (CNS). The secondary involvement of ovary by disseminated lymphoma is much more common than primary form and can be seen in 7&% patients.[1] The primary ovarian lymphoma is rare with an incidence of 0.5% of NHL and 1.5% of ovarian tumors.[2] It is hypothesized to occur in the lymphocyte within the ovarian blood vessels.[3] The criteria for diagnosing primary ovarian lymphoma as defined by Fox and Langley include (a) the disease to be limited to the ovary, (b) no evidence of disease in peripheral blood and bone marrow, and (c) a gap of few months before extraovarian deposits should appear, if any. However, if there is involvement of an adjacent organ or draining lymph node in the absence of systemic disease, the lymphoma is still regarded as primary ovarian lymphoma, as in our case.[3]

The ovarian involvement can be unilateral or bilateral. Most patients present with a constellation of nonspecific symptoms including abdominal or pelvic pain, abnormal vaginal bleeding, nausea, vomiting, bowel obstruction, and abdominal mass with a rapid growth. Although because of increased weight of the ovaries and hypervascularity, there is tendency for partial torsion but only few cases are reported in literature where ovarian torsion was the presenting symptom. The ovarian lymphoma can present like the other common tumors with ascites, omental deposits, pleural effusion, bone marrow, and CNS involvement. The distinction of primary ovarian lymphoma from the more common ovarian malignancies such as epithelial tumors or metastasis is important since the treatment and prognosis differs.

There are no specific imaging characteristics that can differentiate ovarian lymphoma from other ovarian neoplasms. Transvaginal ultrasound may depict the enlargement of ovaries. Cystic appearance without posterior acoustic enhancement is suggestive but nonspecific. Preoperative CT and MRI are helpful for staging and surgical planning and delineating the involvement of other adjacent structures. Absence of generalized lymphadenopathy was helpful in excluding secondary lymphoma. Positron-emission CT is especially useful for determining the extent of involvement before therapy and for assessment of response after therapy.

The definite diagnostic workup of BL consists of histopathology and immunochemistry. Frozen section alone is insufficient for a definitive diagnosis. Mainstay of treatment of ovarian lymphoma is chemotherapy. The role of surgical debulking is controversial with surgery recommended only for acute emergencies. Prognosis depends on the extent of involvement and histological subtype. Overall, the survival rate varies from 50% to 70% with complete remission seen in 75

| Figure.1(a) Color Doppler ultrasound of the pelvis demonstated hypoechoic enlargement of both ovaries with reduced flow. (b) Coronal computer tomography scan of the abdomen revealed solid masses replacing both the ovaries with decreased attenuation of the right ovarian mass

| Figure.2Magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis demonstrated bilateral ovarian masses abutting the uterine fundus, which were hyperintense on T2-weighted image (a) and hypointense on T1-weighted image (b). The lesions demonstrated restriction on diffusion-weighted imaging (c) and heterogonous enhancement on postcontrast sequence (d)

| Figure.3A whole body positron emission tomography computed tomography was performed for staging revealed uptake in both ovaries and left paraaortic lymph node

| Figure.3(a and b) Axial and sagittal postoperative computer tomography scan of the abdomen demonstrated pelvic abscess. (c and d) The abscess was drained under computed tomography guidance

References

- Hu R, Miao M, Zhang R, Li Y, Li J, Zhu K. et al. Ovary involvement of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Case Rep 2012; 13: 96-8

- Cyriac S, Srinivas L, Mahajan V, Sundersingh S, Sagar TG. Primary Burkitt's lymphoma of the ovary. Afr J Paediatr Surg 2010; 7: 120-1

- Pandey S, Devanand B, John BJ, Singh G, Sivanandam S, Leelakrishnan V. et al. High-grade non-hodgkin's lymphoma of ovary presenting as peritonitis. J Cancer Res Ther 2015; 11: 663

- Burkitt D. A sarcoma involving the jaws in African children. Br J Surg 1958; 46: 218-23

- Lu SC, Shen WL, Cheng YM, Chou CY, Kuo PL. Burkitt'S lymphoma mimicking a primary gynecologic tumor. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2006; 45: 162-6

- Hecht JL, Aster JC. Molecular biology of Burkitt's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2000; 18: 3707-21

- Bianchi P, Torcia F, Vitali M, Cozza G, Matteoli M, Giovanale V. et al. An atypical presentation of sporadic ovarian Burkitt's lymphoma: Case report and review of the literature. J Ovarian Res 2013; 4: 46

- Blum KA, Lozanski G, Byrd JC. Adult Burkitt leukemia and lymphoma. Blood 2004; 104: 3009-20

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share