Nonrhabdomyosarcomatous abdominopelvic sarcomas: Analysis of prognostic factors

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2016; 37(02): 100-105

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/0971-5851.180134

Abstract

Background: Data concerning treatment outcome and prognostic factors in sarcomas of abdomen and pelvis are sparse in literature.Methods and Results: Of 696 patients with nonrhabdomyosarcomatous soft tissue sarcoma registered at our center between June 2003 and December 2012, 112 (16%) patients of sarcomas arising from abdomen and pelvis were identified, of which 88 patients were analyzed for treatment outcome and prognostic factors. The median age was 40 years (range: 1–78 years) with a male: female ratio of 0.7:1. Twenty-one (24%) patients were metastatic at baseline. The most common tumor sites were retroperitoneum in 70% patients and abdominal wall in 18% patients. Leiomyosarcoma was the most common histological subtype in 36% patients followed by liposarcoma in 17% patients. Thirty-five (40%) patients had Grade III tumors. Forty-six (52%) patients underwent surgical resection. At a median follow-up of 43 months (range: 2–94 months), the 5-year event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) were 35% and 42%, with a median of 22 months and 43 months, respectively. Multivariate analysis identified male gender (P - 0.03, hazard ratio [HR] - 0.46, 95% confidence interval [CI] - 0.23–0.92), baseline metastatic disease (P - 0.01, HR - 2.98, 95% CI - 1.27–6.98) and Grade III tumors (P - 0.02, HR - 1.84, 95% CI - 1.08–3.13) as factors associated with poor EFS, whereas baseline metastatic disease (P < 0.001, HR - 5.45, 95% CI - 2.31–12.87) and unresectability (P - 0.01, HR - 2.72, 95% CI - 1.27–5.83) were associated with poor OS. Conclusion: This is a single-institutional study of patients with abdominopelvic sarcomas where gender was identified as a new factor affecting survival apart from baseline presentation, histologic grade, and surgical resection.

Publication History

Article published online:

12 July 2021

© 2016. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Background:

Data concerning treatment outcome and prognostic factors in sarcomas of abdomen and pelvis are sparse in literature.

Methods and Results:

Of 696 patients with nonrhabdomyosarcomatous soft tissue sarcoma registered at our center between June 2003 and December 2012, 112 (16%) patients of sarcomas arising from abdomen and pelvis were identified, of which 88 patients were analyzed for treatment outcome and prognostic factors. The median age was 40 years (range: 1–78 years) with a male: female ratio of 0.7:1. Twenty-one (24%) patients were metastatic at baseline. The most common tumor sites were retroperitoneum in 70% patients and abdominal wall in 18% patients. Leiomyosarcoma was the most common histological subtype in 36% patients followed by liposarcoma in 17% patients. Thirty-five (40%) patients had Grade III tumors. Forty-six (52%) patients underwent surgical resection. At a median follow-up of 43 months (range: 2–94 months), the 5-year event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) were 35% and 42%, with a median of 22 months and 43 months, respectively. Multivariate analysis identified male gender (P - 0.03, hazard ratio [HR] - 0.46, 95% confidence interval [CI] - 0.23–0.92), baseline metastatic disease (P - 0.01, HR - 2.98, 95% CI - 1.27–6.98) and Grade III tumors (P - 0.02, HR - 1.84, 95% CI - 1.08–3.13) as factors associated with poor EFS, whereas baseline metastatic disease (P < 0.001, HR - 5.45, 95% CI - 2.31–12.87) and unresectability (P - 0.01, HR - 2.72, 95% CI - 1.27–5.83) were associated with poor OS.

Conclusion:

This is a single-institutional study of patients with abdominopelvic sarcomas where gender was identified as a new factor affecting survival apart from baseline presentation, histologic grade, and surgical resection.

INTRODUCTION

Sarcomas arising in abdomen and pelvis constitute 25–30% of all soft tissue sarcomas (STS), of which retroperitoneal sarcomas account for 15%, and intra-abdominal sarcomas account for 10–15%; < 5% of sarcomas appear as primary abdominal wall tumors.[1,2] The most commonly encountered histologic subtypes of retroperitoneal sarcomas are liposarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, fibrosarcoma, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor.[3,4,5] The most common gynecological sarcomas occur in the uterus and comprise the histological subtypes: Leiomyosarcoma and endometrial stromal sarcoma. STS of the anterior abdominal wall include liposarcoma, synovial sarcoma, fibrosarcoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP), and others.[3,4,5] Surgery is the standard treatment for abdominopelvic sarcomas. Complete margin-negative resections are difficult to achieve in retroperitoneal sarcomas in view of large size and complex anatomy.[6,7,8] The efficacy of adjuvant radiation in abdominopelvic sarcomas has not been demonstrated. Treatment for advanced or metastatic disease consists of systemic chemotherapy with mostly palliative intent.

Limited data exist on treatment outcome and prognostic factors in patients with abdominopelvic sarcomas. To fill these lacunae in literature, we aimed to review our experience with 88 patients of abdominopelvic sarcomas treated at our center over a 10-year period.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study involves data review of all patients with proven diagnosis of abdominopelvic nonrhabdomyosarcomatous sarcomas treated at our department from June 2003 to December 2012. Data were retrieved from the database at our cancer center. Exclusion criteria were patients in whom complete information on the clinical profile was not available, patients who received ≤ 2 cycles of chemotherapy at our center and were lost to follow-up without progression or event and patients in whom response was not evaluated. The tumors were categorized on the basis of site of origin into (a) retroperitoneal tumors (those arising from retroperitoneum and pelvis), (b) tumors of intra-abdominal and pelvic organs. Since there were no intra-abdominal tumors in our study, those arising from uterus and vagina were included in this category and[3] abdominal wall tumors. Baseline demographic profile, clinical characteristics, treatment given, outcome, and treatment-related toxicities (according to National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0) were collected for all patients.

Diagnostic workup

Data on physical examination and local extent of disease were collected for all patients. All patients underwent biopsy (trucut/incisional) of primary lesion with immunohistochemistry. Evaluation of primary disease was done by computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging. Metastatic work-up included chest radiograph and/or chest CT, abdominal ultrasound/CT abdomen, and bone scan wherever required.

Treatment and response evaluation

Treatment protocol consisted of surgery, radiotherapy, and systemic chemotherapy. For patients with localized disease, treatment consisted of surgical resection followed by adjuvant therapy. For patients with unresectable and metastatic disease, systemic chemotherapy was given as the primary modality of treatment. Different chemotherapy regimens were used depending on histology and performance status. Most commonly used regimen was a combination of ifosfamide and doxorubicin. Response to chemotherapy was assessed radiologically after 2 cycles and at the completion of therapy. Complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD) were defined according to Revised Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1.[9]

The following variables were analyzed for their potential prognostic value: Age, gender, baseline presentation (localized or metastatic), duration of symptoms, baseline Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, baseline serum albumin, tumor size, tumor site, histological subtype, grade, and the type of treatment received.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented with mean and standard deviation. Survival was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Data were censored on 31 December 2014. Event-free survival (EFS) was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of disease relapse or progression or death from any cause. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of initial diagnosis to the date of death (whatever the cause) or last follow-up. A univariate Cox proportional hazard model followed by stepwise multivariate Cox regression analysis was done to identify the predictors of outcome. Factors with significance (P ≤ 0.05) in univariate analysis were taken into multivariate analysis. STATA/SE 11.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Clinicopathologic characteristics

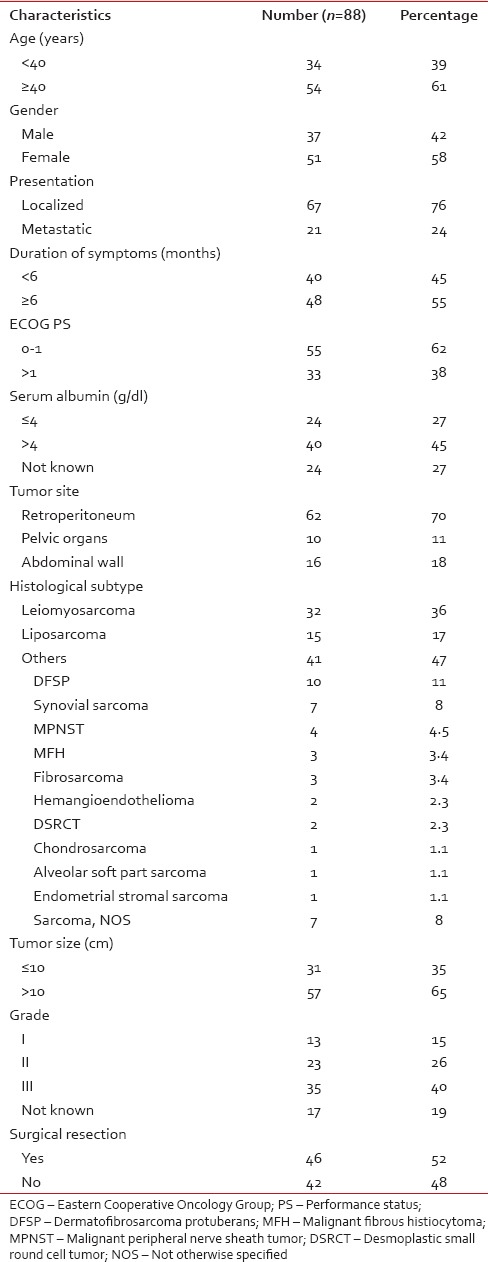

Of 696 patients with nonrhabdomyosarcomatous STS, 112 (16%) patients had sarcomas arising from abdomen and pelvis. Twenty-four patients were excluded (14 patients who did not take treatment and 10 patients who took ≤2 cycles of chemotherapy). Hence, here, we have analyzed 88 patients, and their clinicopathologic characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

Clinicopathologic characteristics of 88 patients

Median age was 40 years (range: 1–78 years) with a median duration of symptoms of 8 months (range: 1–360 months). Median tumor size was 12 cm (range: 3.9–29 cm). The most common histological subtypes were leiomyosarcoma (36%) and liposarcoma (17%).

Treatment

Surgery

Forty-six (52%) patients underwent surgical resection out of which wide excision was performed on 43 patients and marginal resection in 3 patients. Negative margins were achieved in 34 patients. Of 46 patients who underwent surgical resections, 23 patients had primary tumors located in the retroperitoneum, 15 had abdominal wall primary, and 8 patients had uterine tumors. Thirty-three (72%) patients received adjuvant therapy (radiotherapy alone in 14 patients, chemotherapy alone in 7 patients, and chemotherapy plus radiotherapy in 12 patients).

Chemotherapy

Sixty-one (69%) patients received systemic chemotherapy. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy was given in 4 patients. Nineteen patients received adjuvant chemotherapy and 42 patients received systemic chemotherapy as a primary therapy with palliative intent. Of 42 patients who received chemotherapy with palliative intent, 21 patients had unresectable disease at baseline, and 21 patients were metastatic. Thirty-one patients received ifosfamide-doxorubicin combination, 23 patients received single agent doxorubicin, and 7 patients received gemcitabine-docetaxel combination. The response evaluation in these 42 patients was as follows: CR in 5 (12%) patients and PR in 6 (14%) patients. SD was seen in 17 (40%) patients and 14 (33%) patients developed PD. Two patients developed Grade III myelosuppression (both with ifosfamide-doxorubicin regimen). There was one death due to febrile neutropenia.

Survival and prognostic factors

At a median follow-up of 43 months (range: 2–94 months), the 5-year EFS and OS of whole cohort were 35% and 42%, with a median of 22 months and 43 months, respectively.

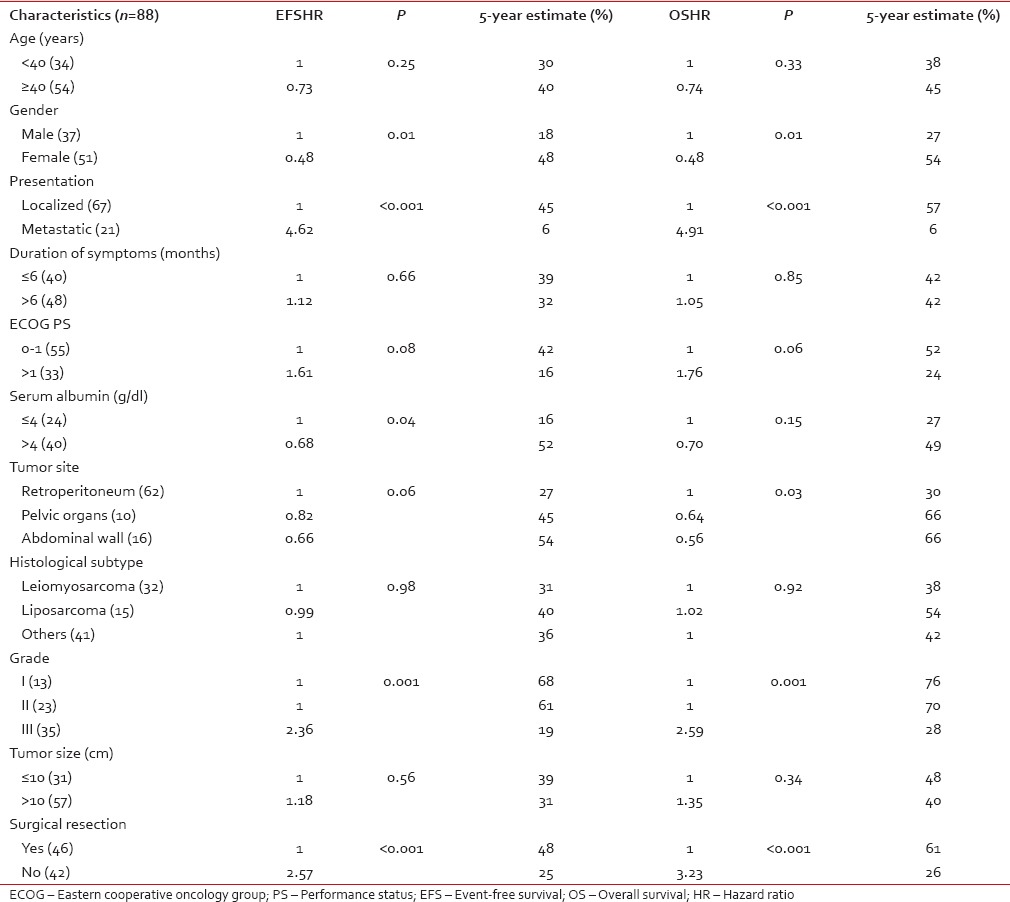

Univariate analysis

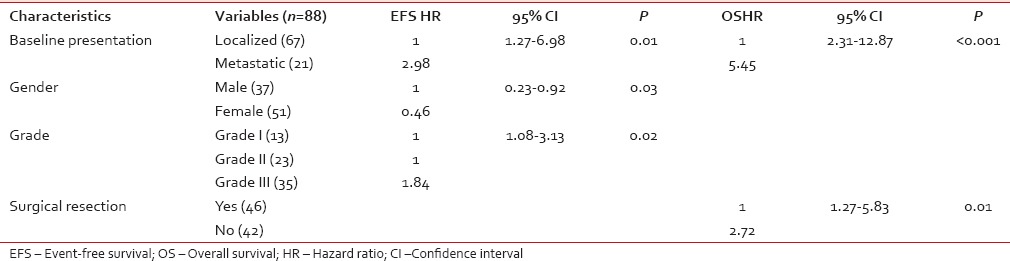

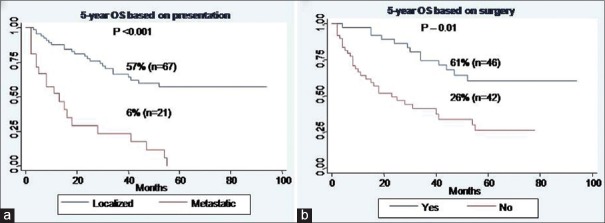

For EFS, univariate analysis identified male gender (P - 0.01), baseline metastatic disease (P < 0.001), serum albumin ≤ 4 g/dl (P - 0.04), Grade III tumors (P - 0.001), and unresectability (P < 0.001) as factors predictive of poor survival. For OS, male sex (P - 0.01), baseline metastatic disease (P < 0.001), retroperitoneal disease (P - 0.03), Grade III tumors (P - 0.001), and unresectability (P < 0.001) were associated with poor survival [Table 2].

Table 2

Factors affecting event-free survival and overall survival in univariate analysis

Multivariate analysis

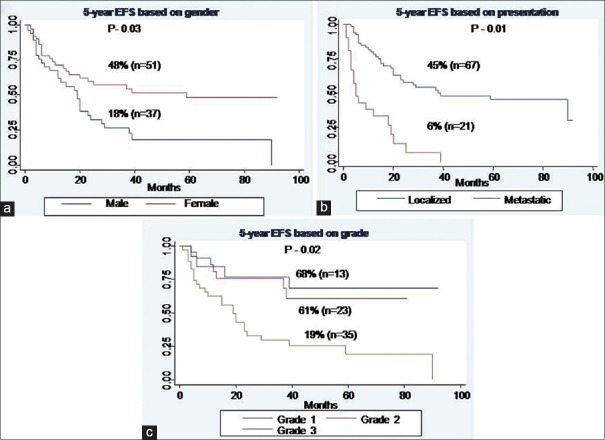

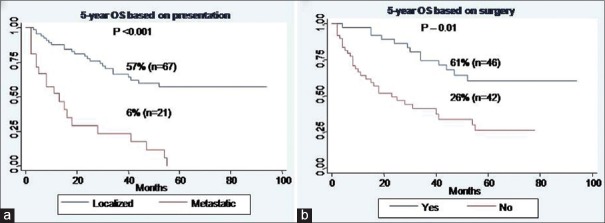

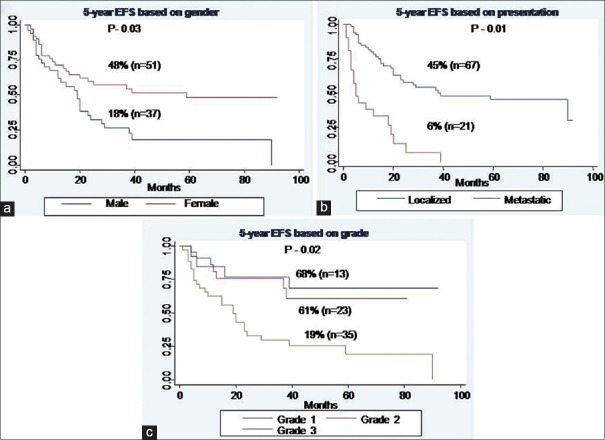

For EFS, male gender (P - 0.03), baseline metastatic disease (P - 0.01), and Grade III tumors (P - 0.02) were identified as poor prognostic factors [Figure [Figure1a1a–c], whereas for OS, baseline metastatic disease (P < 0.001), and unresectability (P - 0.01) emerged as poor prognostic factors [Figure [Figure2a

2a and andb]b] [Table 3].

| Fig. 1 Event-free survival of whole cohort. (a) Based on gender. (b) Based on presentation. (c) Based on grade

| Fig. 2 Overall survival of whole cohort. (a) Based on presentation. (b) Based on surgery

Table 3

Multivariate analysis of factors affecting event-free survival and overall survival

DISCUSSION

A unique feature of many retroperitoneal and pelvic sarcomas concerns their large size at the time of diagnosis[10,11] which was reflected in our study also as 65% patients had tumors measuring >10 cm in size. We observed leiomyosarcoma as the most common histologic subtype arising in retroperitoneum and uterus, whereas DFSP and synovial sarcoma were the most common histologic subtypes in the abdominal wall. This distribution of histologic subtypes was consistent with literature.[3,4,5]

The most significant factors which affected survival in our study were baseline disease presentation, histologic grade, gender, and surgical resection. It is well-known that the long-term survival from sarcomas is most dependent on the completeness of resection and that complete resection remains the only chance for long-term survival.[10,12,13] This was also reflected in our study as patients who underwent surgical resection had a 5-year survival of 61% as compared to 26% for those who were treated with systemic chemotherapy alone. The identification of prognostic factors other than the adequacy of resection has been inconsistent across studies. Tumor size >5 cm is a poor prognostic factor for abdominal wall sarcomas[14] but has not been identified as a predictor of survival in retroperitoneal sarcomas since virtually all retroperitoneal sarcomas are larger than 5 cm at presentation.[3,15] Tumor grade has been reported as a significant factor in some studies, with the weight of evidence supporting shorter recurrence-free and OS for patients with high-grade tumors.[16,17] Our study clearly demonstrates the impact of grade on survival as patients having Grade III tumors did worse compared to Grade I/II tumors (5-year OS; Grade I - 76% vs. Grade II - 70% vs. Grade III - 28%, P - 0.001).

Interestingly, gender was found to impact survival in our study as EFS was worse in males compared to females. The reason for this gender difference is not known as this has not been observed in any other published study. However, some studies focusing on molecular expression profiling have seen gender-specific differences in survival in STS. Sorbye et al. studied the prognostic significance of expression of S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 related to gender, estrogen receptor, and progesterone receptor in STS. In men, but not women, estrogen receptor positive/progesterone receptor negative co-expression profile was an independent negative prognostic factor for disease-specific survival.[18] Another study by Valkov et al. showed that estrogen receptor positivity was a significant favorable indicator for disease-specific survival in women (P = 0.017), while progesterone receptor positivity had inverse impact in men (P = 0.001).[19] The impact of gender on survival in STS is unclear and needs to be confirmed by other studies.

CONCLUSION

Sarcomas of abdomen and pelvis constitute a diverse group of tumors where baseline metastatic disease, high-grade tumors, male gender, and unresectability have a negative impact on survival. More studies are required to derive any meaningful conclusion on the prognostic impact of gender so that the treatment can be optimized depending on high-risk characteristics of patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the editorial assistance of Ms. Deepa Dhawan.

REFERENCES

| Fig. 1 Event-free survival of whole cohort. (a) Based on gender. (b) Based on presentation. (c) Based on grade

| Fig. 2 Overall survival of whole cohort. (a) Based on presentation. (b) Based on surgery

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share