Neoplasms of the Head and Neck in Iranian Children and Adolescents

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2020; 41(05): 677-682

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/ijmpo.ijmpo_164_19

Abstract

Introduction: Head and neck neoplasms afflict all age groups including children. They manifest with various histological features and clinical behaviors. This study's aim was to provide data and analysis of the prevalence of head and neck neoplasms among the Iranian children and adolescents to help pathologists and clinicians make informed diagnosis and treatment decisions. Materials and Methods: This retrospective study was based on medical records of children and adolescents (≤18 years) documented at a prestigious children's medical center stationed in Tehran, Iran. Cases diagnosed with head and neck tumors recorded from 2005 to 2016 were selected. Patients' age and sex, tumors' sites, and microscopic types were assessed. Data analysis was performed using descriptive statistics. Results: Of the 41,409 available pediatric patients' records documented over 12 years, 418 cases (1.01%) recorded head and neck tumors. Of these 418 cases, 15 recorded metastatic tumors (3.58%) and 403 recorded primary tumors. Of the primary tumors, 386 were found in the soft tissue (95.78%) and 17 in the bone (4.22%). The primary tumor patients' mean age was 5.46 years, including boys (59.8%) and girls (40.2%). The neck was the most common primary tumors' location (57.32%). Of all the primary tumors, 54.6% were benign neoplasms and 45.4% malignant. The commonest benign tumors were hemangioma/lymphangioma, and the most common malignancy was lymphoma. Mesenchymal neoplasms were the most common microscopic group followed by hematopoietic tumors. Conclusions: The analysis of these data indicates that the prevalence of pediatric head and neck tumors in the Iranian population is similar to other countries.

Keywords

Children - head and neck tumor - hemangioma - lymphoma - malignantPublication History

Received: 01 August 2019

Accepted: 03 April 2020

Article published online:

17 May 2021

© 2020. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Introduction: Head and neck neoplasms afflict all age groups including children. They manifest with various histological features and clinical behaviors. This study's aim was to provide data and analysis of the prevalence of head and neck neoplasms among the Iranian children and adolescents to help pathologists and clinicians make informed diagnosis and treatment decisions. Materials and Methods: This retrospective study was based on medical records of children and adolescents (≤18 years) documented at a prestigious children's medical center stationed in Tehran, Iran. Cases diagnosed with head and neck tumors recorded from 2005 to 2016 were selected. Patients' age and sex, tumors' sites, and microscopic types were assessed. Data analysis was performed using descriptive statistics. Results: Of the 41,409 available pediatric patients' records documented over 12 years, 418 cases (1.01%) recorded head and neck tumors. Of these 418 cases, 15 recorded metastatic tumors (3.58%) and 403 recorded primary tumors. Of the primary tumors, 386 were found in the soft tissue (95.78%) and 17 in the bone (4.22%). The primary tumor patients' mean age was 5.46 years, including boys (59.8%) and girls (40.2%). The neck was the most common primary tumors' location (57.32%). Of all the primary tumors, 54.6% were benign neoplasms and 45.4% malignant. The commonest benign tumors were hemangioma/lymphangioma, and the most common malignancy was lymphoma. Mesenchymal neoplasms were the most common microscopic group followed by hematopoietic tumors. Conclusions: The analysis of these data indicates that the prevalence of pediatric head and neck tumors in the Iranian population is similar to other countries.

Keywords

Children - head and neck tumor - hemangioma - lymphoma - malignantIntroduction

Head and neck tumors include a variety of pathological disorders that may afflict all age groups, 3%–5% of these tumors have been reported to occur in children.[1] Despite all the endeavors to control contagious lesions in the third-world countries, orofacial malignancies are still considered the most important concern in the oral health field. Moreover, face and neck tumors in children, either benign or malignant, could lead to facial deformities and consequently social and psychological problems.[2] Given the involved area, they could affect speaking, swallowing, etc.[3] Therefore, there is a need for conducting basic studies to have a better understanding of the head and neck tumors, which in turn leads to a correct and fast therapeutic intervention. This information will be certainly worthwhile for pediatric physicians.[4]

Tumors may occur in different ages. Any form of delay in providing care and taking proper measures for tumor-afflicted patients, even in the case of benign tumors with an acceptable prognosis could result in disability or death.[5] Most head and neck swellings in children are of an inflammatory nature. Differential diagnosis of such lesions includes cysts, vascular deformations, and tumors, which may be benign or malignant. Malignant neoplasms are rare in children, yet they could have severe and dangerous consequences for pediatric patients.[6] These tumors are considered the second cause of mortality among 4–15-year-old children.[7] Malignancies could be divided into three large groups: carcinomas, sarcomas, and malignancies of hematopoietic system.[8] Previous evaluations have indicated lymphoma, retinoblastoma, and sarcoma to be the most common head and neck malignancies in children, whereas carcinoma is reported only in a small portion of the cases.[1],[2],[4],[7] In general, epidemiologic research with large series could be valuable, as it potentially offers important information on the prevalence of the lesions.[9] Such data for the Iranian children and adolescents are very sparse.[3] Accordingly, the aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of the head and neck benign and malignant tumors in Iranian children and adolescents.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted in full accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and subsequent revisions.[10] The ethics committee of the institution in which the study was conducted approved this study. This cross-sectional retrospective study was conducted based on the medical records of children and adolescents (≤18 years) available in the archive of a prestigious children's medical center stationed in Tehran, Iran. The records dated between 2005 (the earliest of their documentation) and 2016. In order to adhere to ethical principles, the records were anonymized and de-identified records were provided to the researchers. The pathology reports were reviewed and cases with a diagnosis of head and neck tumors were selected. Then, patients' age and sex, tumors' site, and their microscopic types were assessed and classified in tables. The tumors were further classified into four groups based on their histopathologic subtypes: mesenchymal, hematopoietic, epithelial/salivary, and bone/odontogenic. Finally, each group was divided into subgroups based on the tumor's location. Retinoblastoma and brain neoplasms were not evaluated in this study. The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (Pearson Chi-square, exact Chi-square) and SPSS software (IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). The P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

A total of 41,409 medical records of patients documented in the pathology section of Children's Medical Centre (Iran's most prestigious pediatric medical center), during a 12-year period (2005–2016) were reviewed. Of these records, 418 cases recorded head and neck tumors (1.01%), 15 of which were metastatic tumors (3.58%), which were predominant in boys. The mean age of patients afflicted with metastatic tumors was 4.24 years. Neuroblastoma was the most common metastatic tumor (73.34%), and the most commonly involved sites of the metastatic tumors were the face and the neck. Other subsequent data (403 cases) were related to primary neoplasms.

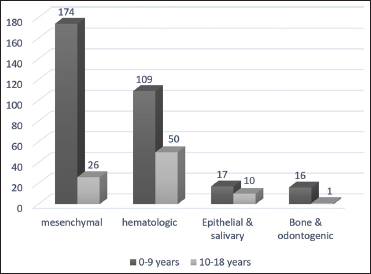

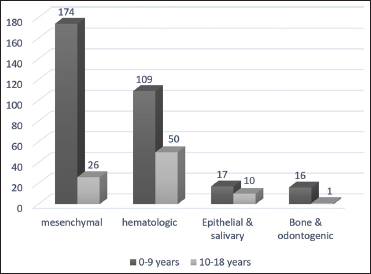

The remaining 403 cases recorded patients afflicted with primary tumors, 386 of which (95.78%) were found in the soft tissue and the other 17 (4.22%) were found in the bone. The mean age of these patients was 5.46 years, and 241 of them were boys (59.8%) and 162 were girls (40.2%). The neck was the most common site of these tumors (57.32). From the total number of cases diagnosed with primary tumors, 54.6% were benign neoplasms while 45.4% were malignant [Table 1]. The mean age of patients with malignant neoplasms was higher than that of benign tumors (11.70 ± 4.14 vs. 10.31 ± 3.18 years). The proportion of malignancy in the second decade of life was significantly higher than in the first decade based on the Pearson Chi-square test (P < 0.0001). Further, the proportion of malignancy was significantly higher in boys (51%) than in girls (37%) based on the Pearson Chi-square test (P = 0.006).

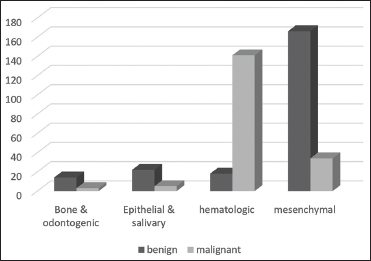

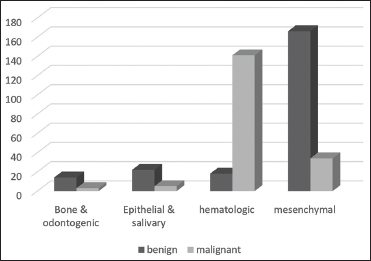

The commonest benign tumors were hemangioma/lymphangioma, and the most common malignancy was lymphoma. Among all the microscopic groups, mesenchymal neoplasms were the most common followed by hematopoietic tumors. The age-specific prevalence of mesenchymal tumors (mean age 3.61 ± 3.81) was significantly lower than that of other types of lesions based on the Pearson Chi-square test (P < 0.0001). Further, there was a significant relationship between the location of tumors and their origin based on the exact Chi-square test (P < 0.0001). In hematopoietic and mesenchymal tumors, the neck was the most involved location, while face involvement was more common in the epithelial group, with bone/odontogenic groups found more in the oral cavity [Table 2].

Distribution of microscopic groups based on tumors’ location

|

Microscopic groups |

Location |

Total |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Neck |

Face |

Oral cavity |

Sinonasal |

Thyroid |

||

|

Hematologic |

118 (74.20) |

29 (18.20) |

12 (7.50) |

0 (0.00) |

0 (0.00) |

159 |

|

Mesenchymal |

102 (51.00) |

49 (24.50) |

42 (21.00) |

7 (3.50) |

0 (0.00) |

200 |

|

Epithelial and salivary |

9 (33.30) |

11 (40.70) |

4 (14.80) |

1 (3.70) |

2 (7.40) |

27 |

|

Bone and odontogenic |

2 (11.80) |

2 (11.80) |

13 (76.50) |

0 (0.00) |

0 (0.00) |

17 |

|

Total |

231 (57.30) |

91 (22.60) |

71 (17.60) |

8 (2.00) |

2 (0.50) |

403 (100.00) |

| Figure 1: Distribution of benign and malignant tumors based on microscopic groups

| Figure 2:Distribution of microscopic groups for two decades of life

The most common location for the hematopoietic and mesenchymal microscopic groups was the neck. Mesenchymal tumors were more common in males. In the epithelial group, the mean age of patients was 7.37 ± 4.72 and the most common tumor was pilomatrixoma, which was more common in boys. In the oral cavity, most common neoplasms were mesenchymal (59.2%) followed by bone/odontogenic (18.3%).

Discussion

In this study, the prevalence rate of head and neck tumors was 1.01% in the population of children and adolescents, which is in agreement with some studies,[3],[5],[11] while incongruent with some others [Table 3].[1],[2],[6],[12],[13] A reason for this low percentage in the current study may be that many lesions in children were not neoplastic (such as cysts and inflammatory-infectious lesions).

Table 3 Comparison of the results of the present study with pervious published articles

Metastatic tumors

Metastatic tumors appeared in 3.58% of cases, with neuroblastoma as the most common metastatic neoplasm. Barnes[18] indicated that the most common metastatic tumors in the first two decades of life were adrenal neuroblastoma, osteosarcoma, and PNET/Ewing sarcoma, respectively. In addition, Cunningham et al.[16] found that 66.67% of neuroblastoma in their study were metastatic.

Primary tumors

Regarding primary tumors, soft-tissue neoplasms were far more common than hard tissue ones. This result is similar to some reports.[5],[12] On the other hand, Aregbesola et al.,[1] as well as Omoregie and Akpata[2] found higher rates of osteogenic tumors. A possible cause for this discrepancy is that the two mentioned studies ignored neck lesions.

Overall, benign tumors were more common than malignant ones (ratio: 1.20), which is consistent with most studies; however, previously reported percentages were different.[2],[3],[5],[6],[11],[12],[13],[19] The higher rate of malignant tumors in the studies of Aregbesola et al.[1] and Rapidis et al.[14] may be due to their specific geographical region, as their studies were conducted in Nigeria in which Burkitt's lymphoma has a high prevalence. However, Khademi et al.[15] found a high percentage of malignancy in their study (89%). In our study, the mean age was 5.46 years, and the tumors were more common in boys, which is consistent with other studies.[1],[2],[3],[5],[12],[13],[14],[15],[19] However, the overall comparison of age groups in children was difficult, since, in various studies, different age ranges had been analyzed, for example, ages under 12 years old,[5],[20] under 16 years old,[2],[6],[14] and under 18 years old[3],[11],[21],[22] were some age ranges analyzed in different studies. The most common location for tumors was the neck, which is consistent with studies conducted by Fattahi et al.[5] and Rapidis et al.,[14] but they are incongruent with the results of another study.[6]

The most common benign tumor was hemangioma/lymphangioma and the most common malignant neoplasm was lymphoma. These tumors were also observed as the most common tumors in other studies.[5],[6],[14] Pilomatrixoma and Langerhans cell histiocytosis ranked the second among benign neoplasms. However, in a study conducted by Rapidis et al.,[14] squamous papilloma was in the second place. This low rate of papilloma in the Iranian children and adolescents indicates a low infection rate of the human papilloma virus among this population.

Primary mesenchymal tumors

Among the microscopic subgroups, mesenchymal tumors had the highest frequency which is consistent with some studies.[3],[5],[11],[12],[13],[23] The highest frequency was seen in ≤9 years age range (mean 3.61 years) where the ratio of benign to malignant tumors in this group was 4.88, which was more common in boys. These results are in agreement with the findings of the study conducted by Jaafari-Ashkavandi and Ashraf.[3] However, in other studies, the number of girls afflicted with such mesenchymal tumors was higher[1],[11] or equal.[12] Again, the neck was the most commonly involved area. The most common microscopic subtype in this group was vascular lesions (hemangioma/lymphangioma). This result is in agreement with other studies.[1],[3],[5],[12] The most common malignancy in this group was rhabdomyosarcoma, which is similar to reports made by Cunningham et al.[16] and Khademi et al.[15] In the present study, sarcomas (bone and soft tissue) (20.22%) were the second-most common malignancies while carcinomas (2.73%) were found in a few cases. These findings are the same as the results of other studies.[7],[12],[16] However, Khademi et al.[15] reported the opposite, i.e., the frequency of carcinoma was higher. In our study, rhabdomyosarcoma was the most common sarcoma followed by PNET/Ewing.

Primary hematologic tumors

The second most common microscopic group after the mesenchymal tumors was the hematologic lesions, with a malignant-to-benign ratio of 7.83. These lesions had a significant frequency in ≤9 years of age group where most cases were in the lymphoma subtype (73.4%) which is consistent with other studies.[1],[3],[7],[15],[20] The highest frequency was seen in boys as also found by other studies,[4],[7],[15],[20],[24] and the most commonly involved area was the neck which is in agreement with other research.[15],[24] Similar to some studies,[3],[16],[24] the mean age in lymphoma was 8.15. In the study of Khademi et al.,[15] lymphoma occurred in children and adolescents equally. In the current research, the percentages of Hodgkin's and non-Hodgkin's lymphomas were 47.79% and 22.01%, respectively. In the studies of Cunningham et al.,[16] Torsiglieri et al.,[19] and Rapidis et al.,[14] Hodgkin's lymphoma was more common, while in other studies non-Hodgkin's lymphoma had a higher frequency.[2],[5],[7],[11],[15],[17],[20],[24]

Primary epithelial/salivary tumors

In the present study, epithelial/salivary tumors were in the third place among the microscopic groups, most of which were benign. The mean age of patients afflicted with these tumors was 7.37 years and a higher frequency was seen in boys and in the face area. Pilomatrixoma was the most common subtype in this group with a mean age of 5.12 years, which was predominant in boys and in the face and neck areas. In the study of Schwarz et al.,[25] conducted on 318 children afflicted by Pilomatrixoma of head and neck, the number of afflicted girls was higher than that of boys, and the mean age of patients was 6.7 years; 75% and 25% of cases had head and neck involvement, respectively.

Primary bone/odontogenic tumors

In the group of bone/odontogenic tumors, the benign-to-malignant ratio was 4.6, and the only mentioned malignancy in this group was Ewing sarcoma. The mean age of patients was 4.32 years, with male predominance and the most commonly involved area was the oral cavity (76.5%). In the study conducted by Khademi et al.,[15] Ewing sarcoma also claimed the second rank (following Rhabdomyosarcoma), but the most common site was paranasal sinuses. In several studies, ameloblastoma was mentioned to be the most common odontogenic tumor in this age group[1],[13] although we found ameloblastic fibroma as the most common condition. Confirming our study, Tanrikulu et al.[23] found a higher rate of mixed odontogenic tumors in their research. Some studies had reported that among all bone tumors, ossifying fibroma,[12],[13] central giant cell granuloma,[12] and fibrous dysplasia[1] had higher frequencies. However, in our research, Ewing sarcoma was the most common osteogenic bone tumor.

Conclusions

One of the strong points of this epidemiologic study about children is its large sample size, which makes its statistical results reliable. The current study's results indicated that in Iranian children and adolescents, benign tumors were more common than malignant tumors. Lymphoma and rhabdomyosarcoma were the most common malignancies in the studied age group ≤18 years (apart from the central nervous system neoplasms and retinoblastoma). Further, the most common benign tumors were hemangioma/lymphangioma. The tumors were more common in boys than girls. All these data suggest that the prevalence of pediatric head and neck tumors and their subtypes in Iranian population are mostly similar to other countries. This study provides a large series of demographic data and histopathologic variations of head and neck tumors in Iranian children and adolescents, which will contribute to accurate diagnosis and enhanced treatment of these neoplasms. The main limitation faced in this study was a lack of complete data on clinical signs, treatment methods, patient survival, and tumor prognosis due to improper follow-up documentation. All of which offer intriguing suggestions for further study.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The assistance of the staff members of “Children's Medical Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran” in providing the medical records is highly appreciable.

References

- Aregbesola SB, Ugboko VI, Akinwande JA, Arole GF, Fagade OO. Orofacial tumours in suburban Nigerian children and adolescents. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005; 43: 226-31

- Omoregie FO, Akpata O. Paediatric orofacial tumours: New oral health concern in paediatric patients. Ghana Med J 2014; 48: 14-9

- Jaafari-Ashkavandi Z, Ashraf MJ. A clinico-pathologic study of 142 orofacial tumors in children and adolescents in Southern Iran. Iran J Pediatr 2011; 21: 367-72

- Okumu SB, Chindia ML, Gathece LW, Dimba EA, Odhiambo W. Clinical features and types of paediatric orofacial malignant neoplasms at two hospitals in Nairobi, Kenya. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2012; 40: e8-14

- Fattahi S, Vosoughhosseini S, Moradzadeh Khiavi M, Mahmoudi SM, Emamverdizadeh P, Noorazar SG. et al. Prevalence of head and neck tumors in children under 12 years of age referred to the pathology department of children's hospital in Tabriz during a 10 year period. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospect 2015; 9: 96-100

- Abdulai AE, Nuamah IK, Gyasi R. Head and neck tumours in Ghanaian children. A 20 year review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012; 41: 1378-82

- Ajayi OF, Adeyemo WL, Ladeinde AL, Ogunlewe MO, Omitola OG, Effiom OA. et al. Malignant orofacial neoplasms in children and adolescents: A clinicopathologic review of cases in a Nigerian tertiary hospital. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2007; 71: 959-63

- Akbari ME, Atarbashi Moghadam S, Atarbashi Moghadam F, Bastani Z. Malignant Tumors of Tongue in Iranian Population. Iran J Cancer Prev 2016; 9: e4467

- Atarbashi-Moghadam S, EmamiRazavi AN, SalehiZalani S. Prevalence of head and neck sarcoma in a major cancer center in Iran- A 10-year study. Iran J Otorhinolaryngol 2019; 31: 97-102

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013; 310: 2191-4

- Elarbi M, El-Gehani R, Subhashraj K, Orafi M. Orofacial tumors in Libyan children and adolescents. A descriptive study of 213 cases. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2009; 73: 237-42

- Al-Khateeb T, Al-Hadi Hamasha A, Almasri NM. Oral and maxillofacial tumours in north Jordanian children and adolescents: A retrospective analysis over 10 years. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003; 32: 78-83

- Arotiba GT. A study of orofacial tumors in Nigerian children. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1996; 54: 34-8

- Rapidis AD, Economidis J, Goumas PD, Langdon JD, Skordalakis A, Tzortzatou F. et al. Tumours of the head and neck in children. A clinico-pathological analysis of 1,007 cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 1988; 16: 279-86

- Khademi B, Taraghi A, Mohammadianpanah M. Anatomical and histopathological profile of head and neck neoplasms in Persian pediatric and adolescent population. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2009; 73: 1249-53

- Cunningham MJ, Myers EN, Bluestone CD. Malignant tumors of the head and neck in children: A twenty-year review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1987; 13: 279-92

- Arboleda LP, Hoffmann IL, Cardinalli IA, Santos-Silva AR, de Mendonça RM. Demographic and clinicopathologic distribution of head and neck malignant tumors in pediatric patients from a Brazilian population: A retrospective study. J Oral Pathol Med 2018; 47: 696-705

- Barnes L. Metastases to the head and neck: An overview. Head Neck Pathol 2009; 3: 217-24

- Torsiglieri Jr. AJ, Tom LW, Ross 3rd AJ, Wetmore RF, Handler SD, Potsic WP. Pediatric neck masses: Guidelines for evaluation. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1988; 16: 199-210

- Sengupta S, Pal R, Saha S, Bera SP, Pal I, Tuli IP. Spectrum of head and neck cancer in children. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg 2009; 14: 200-3

- Chung SY, Unsal AA, Kılıç S, Baredes S, Liu JK, Eloy JA. Pediatric sinonasal malignancies: A population-based analysis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2017; 98: 97-102

- Saeed H, Zaidi A, Adhi M, Hasan R, Dawson A. Pediatric nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A review of 27 cases over 10 years at Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Center, Pakistan. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2009; 10: 917-20

- Tanrikulu R, Erol B, Haspolat K. Tumors of the maxillofacial region in children: Retrospective analysis and long-term follow-up outcomes of 90 patients. Turk J Pediatr 2004; 46: 60-6

- Roh JL, Huh J, Moon HN. Lymphomas of the head and neck in the pediatric population. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2007; 71: 1471-7

- Schwarz Y, Pitaro J, Waissbluth S, Daniel SJ. Review of pediatric head and neck pilomatrixoma. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2016; 85: 148-53

Address for correspondence

Publication History

Received: 01 August 2019

Accepted: 03 April 2020

Article published online:

17 May 2021

© 2020. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

| Figure 1: Distribution of benign and malignant tumors based on microscopic groups

| Figure 2:Distribution of microscopic groups for two decades of life

References

- Aregbesola SB, Ugboko VI, Akinwande JA, Arole GF, Fagade OO. Orofacial tumours in suburban Nigerian children and adolescents. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005; 43: 226-31

- Omoregie FO, Akpata O. Paediatric orofacial tumours: New oral health concern in paediatric patients. Ghana Med J 2014; 48: 14-9

- Jaafari-Ashkavandi Z, Ashraf MJ. A clinico-pathologic study of 142 orofacial tumors in children and adolescents in Southern Iran. Iran J Pediatr 2011; 21: 367-72

- Okumu SB, Chindia ML, Gathece LW, Dimba EA, Odhiambo W. Clinical features and types of paediatric orofacial malignant neoplasms at two hospitals in Nairobi, Kenya. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2012; 40: e8-14

- Fattahi S, Vosoughhosseini S, Moradzadeh Khiavi M, Mahmoudi SM, Emamverdizadeh P, Noorazar SG. et al. Prevalence of head and neck tumors in children under 12 years of age referred to the pathology department of children's hospital in Tabriz during a 10 year period. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospect 2015; 9: 96-100

- Abdulai AE, Nuamah IK, Gyasi R. Head and neck tumours in Ghanaian children. A 20 year review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012; 41: 1378-82

- Ajayi OF, Adeyemo WL, Ladeinde AL, Ogunlewe MO, Omitola OG, Effiom OA. et al. Malignant orofacial neoplasms in children and adolescents: A clinicopathologic review of cases in a Nigerian tertiary hospital. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2007; 71: 959-63

- Akbari ME, Atarbashi Moghadam S, Atarbashi Moghadam F, Bastani Z. Malignant Tumors of Tongue in Iranian Population. Iran J Cancer Prev 2016; 9: e4467

- Atarbashi-Moghadam S, EmamiRazavi AN, SalehiZalani S. Prevalence of head and neck sarcoma in a major cancer center in Iran- A 10-year study. Iran J Otorhinolaryngol 2019; 31: 97-102

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013; 310: 2191-4

- Elarbi M, El-Gehani R, Subhashraj K, Orafi M. Orofacial tumors in Libyan children and adolescents. A descriptive study of 213 cases. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2009; 73: 237-42

- Al-Khateeb T, Al-Hadi Hamasha A, Almasri NM. Oral and maxillofacial tumours in north Jordanian children and adolescents: A retrospective analysis over 10 years. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003; 32: 78-83

- Arotiba GT. A study of orofacial tumors in Nigerian children. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1996; 54: 34-8

- Rapidis AD, Economidis J, Goumas PD, Langdon JD, Skordalakis A, Tzortzatou F. et al. Tumours of the head and neck in children. A clinico-pathological analysis of 1,007 cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 1988; 16: 279-86

- Khademi B, Taraghi A, Mohammadianpanah M. Anatomical and histopathological profile of head and neck neoplasms in Persian pediatric and adolescent population. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2009; 73: 1249-53

- Cunningham MJ, Myers EN, Bluestone CD. Malignant tumors of the head and neck in children: A twenty-year review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1987; 13: 279-92

- Arboleda LP, Hoffmann IL, Cardinalli IA, Santos-Silva AR, de Mendonça RM. Demographic and clinicopathologic distribution of head and neck malignant tumors in pediatric patients from a Brazilian population: A retrospective study. J Oral Pathol Med 2018; 47: 696-705

- Barnes L. Metastases to the head and neck: An overview. Head Neck Pathol 2009; 3: 217-24

- Torsiglieri Jr. AJ, Tom LW, Ross 3rd AJ, Wetmore RF, Handler SD, Potsic WP. Pediatric neck masses: Guidelines for evaluation. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1988; 16: 199-210

- Sengupta S, Pal R, Saha S, Bera SP, Pal I, Tuli IP. Spectrum of head and neck cancer in children. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg 2009; 14: 200-3

- Chung SY, Unsal AA, Kılıç S, Baredes S, Liu JK, Eloy JA. Pediatric sinonasal malignancies: A population-based analysis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2017; 98: 97-102

- Saeed H, Zaidi A, Adhi M, Hasan R, Dawson A. Pediatric nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A review of 27 cases over 10 years at Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Center, Pakistan. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2009; 10: 917-20

- Tanrikulu R, Erol B, Haspolat K. Tumors of the maxillofacial region in children: Retrospective analysis and long-term follow-up outcomes of 90 patients. Turk J Pediatr 2004; 46: 60-6

- Roh JL, Huh J, Moon HN. Lymphomas of the head and neck in the pediatric population. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2007; 71: 1471-7

- Schwarz Y, Pitaro J, Waissbluth S, Daniel SJ. Review of pediatric head and neck pilomatrixoma. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2016; 85: 148-53

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share