Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Psychological Well-Being of Health Care Professionals in India

CC BY 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2024; 45(03): 242-248

DOI: DOI: 10.1055/s-0043-1764368

Abstract

Introduction and Objective Health care professionals (HPs) have been at the forefront facing the pressures and uncertainties of the COVID-19 pandemic, and thus have a higher psychological vulnerability. The incidence of psychological distress, which can negatively affect an HP's work efficiency and long-term well-being, has not been studied in depth in India.

Materials and Methods A multicentric study was conducted using the digital means of communication across Max Healthcare between June and August 2020. HPs in the department of oncology, including doctors, nurses, and other support staff, were invited to voluntarily participate in the self-administered online survey. A total of 87 HPs in oncology (41 doctors, 28 nurses, and 18 in other fronts) were assessed using the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12). Outcome of interest was psychological distress (defined as a GHQ-12 score >15).

Results The overall incidence of psychological distress among HPs in oncology during the COVID-19 pandemic was 17.20%. Significantly higher levels of psychological distress were observed among HPs with a history of psychiatric illness (p = 0.003), and among HPs with a work experience of less than 10 years (p = 0.017).

Conclusion The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on the psychological well-being of HPs in India. This study implicated the recognition of the psychological well-being of HPs in oncology as an unmet need during the COVID-19 pandemic, further recommending efforts toward increasing accessibility of mental health services for them.

Keywords

COVID-19 - GHQ-12 - health care professionals - India - psychological - well-being - oncologyClinical Trial Registration

CTRI number: CTRI/2020/05/025220 (Registered on May 17, 2020); protocol code for Institutional Ethics Committee: RS/MSSH/DDF/SKT-2/IEC/S-ONCO/20–13; and date of approval: May 7, 2020.

Publication History

Article published online:

17 April 2023

© 2023. The Author(s). This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, permitting unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction so long as the original work is properly cited. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Introduction and Objective Health care professionals (HPs) have been at the forefront facing the pressures and uncertainties of the COVID-19 pandemic, and thus have a higher psychological vulnerability. The incidence of psychological distress, which can negatively affect an HP's work efficiency and long-term well-being, has not been studied in depth in India.

Materials and Methods A multicentric study was conducted using the digital means of communication across Max Healthcare between June and August 2020. HPs in the department of oncology, including doctors, nurses, and other support staff, were invited to voluntarily participate in the self-administered online survey. A total of 87 HPs in oncology (41 doctors, 28 nurses, and 18 in other fronts) were assessed using the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12). Outcome of interest was psychological distress (defined as a GHQ-12 score >15).

Results The overall incidence of psychological distress among HPs in oncology during the COVID-19 pandemic was 17.20%. Significantly higher levels of psychological distress were observed among HPs with a history of psychiatric illness (p = 0.003), and among HPs with a work experience of less than 10 years (p = 0.017).

Conclusion The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on the psychological well-being of HPs in India. This study implicated the recognition of the psychological well-being of HPs in oncology as an unmet need during the COVID-19 pandemic, further recommending efforts toward increasing accessibility of mental health services for them.

Keywords

COVID-19 - GHQ-12 - health care professionals - India - psychological - well-being - oncologyIntroduction

The emergence of a new coronavirus disease, called COVID-19, has recently caused a tremendous public health crisis globally.[1] It has been observed that the pandemic has affected people all over the world socially, mentally, physically, psychologically, and economically.[2] India was hit by the COVID-19 pandemic in the month of March 2020, when a national lockdown was announced, affecting a large part of its population and adversely impacting the health care systems across the country. This led to unexpected challenges and burdens for health care professionals (HPs) in various public and private setups.[3]

In a review by Vizheh,[4] it was observed that during the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, 29% of all hospitalized patients were HPs. It was also reported that HPs were one of the most vulnerable groups across the world during the COVID-19 pandemic.[5] Thombs et al expressed a concern regarding the vulnerability of adequate medical care for all affected persons in need.[6] They further estimated that prolonged restrictions and isolation exacerbated problems like health, psychological well-being, social functioning, and unemployment. It was further predicted that individual and social economic resources would be insufficient in the near future.[6] Doctors had reported a growing concern and discomfort due to lack of personal protective equipment (PPE), and once the frontline staff had started contracting the disease, other workers became potential threats to subsequent patients.[2] One study identified factors such as heavy workload, fear of infection, concern about family, underlying illness, being an only child, and female gender to be contributing to the health care workers' reduced mental health taking a toll on their psychological well-being.[7] Que et al reported that in comparison to the general population, HPs had faced greater pressure from COVID-19, especially those who had been in contact with suspected or confirmed cases, because of higher risks of infection, loss of control, lack of experience in managing the disease, overwork, perceived stigma, lifestyle changes, isolation, and lesser family support.[1] The specificity of psychopathological expressions among medical professionals was reported to be dependent on both individual factors (e.g., age, sex, and the presence of children) and institutional factors (e.g., the length of service, changes to working time, and the availability of PPE).[8]

The mental health concerns in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic in India are more complex due to a larger proportion of socially and economically vulnerable populations (children, geriatric, migrant laborers, etc.), higher burden of preexisting mental illness,[9] more constrained mental health services infrastructure,[10] less penetration of digital mental health solutions, and, above all, the scare created due to tremendous misinformation on social media.[11] All HPs have been identified to be at an increased risk of mental health concerns, especially oncology professionals who are as it is in constant contact with suffering and death.[12] It has also been seen through several data that several HPs working in oncology care showed symptoms of burnout, attributed to work dissatisfaction, work overload, organizational problems, communication problems, and emotional concerns with patients and colleagues.[13] Therefore, we decided to focus only on the oncology HPs of our health care setup to understand the impact of the pandemic on their psychological well-being.

The aim of our study was to understand the psychological distress among HPs in the department of oncology across a group of tertiary hospitals in the private sector in India, during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study's outcome has implications for planning and providing psychological interventions (or therapeutic services) to HPs.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

Setting

This was a prospective multicentric study conducted on HPs in oncology (including doctors, nurses, and other support staff) across seven units of Max Healthcare (MHC), a cluster of tertiary care hospitals in the Delhi National Capital Region (NCR) of North India. All HPs were employees of MHC, aged >18 years who had voluntarily consented to take part in the study.

Instrument

Psychological distress was assessed using the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12).[14] It is a self-administered screening tool that assesses an individual's inability to carry out one's normal healthy functions and the appearance of psychological distress. It has been found to be reliable and valid.[15] [16]

The 12 statements (see [Appendix A]) were rated on a 4-point scale with a scoring weight of 0 to 3. Thus, the total score was expected to range from 0 to 36. A higher score indicated increased levels of psychological distress and poor general health (scores between 11 and 12: typical; scores >15: evidence of distress).

Although the measuring tool has been validated in three Indian languages (Kannada, Hindi, and Tamil), it was administered in its original English format as the target population was well versed in English.

Conduct of Study

The instrument was self-administered via an online survey. In addition to the 12 statements of GHQ-12, information about the respondent's demographic details, previous history of physical and psychiatric illness, and family circumstances was also collected. The participants were contacted individually via a designated survey link to register responses online, which was distributed through the primary means of digital communication (e-mail addresses, text messages, and WhatsApp). Identifiable information was not collected.

After the first request for participation, two further reminders were sent to all the individual employees and the data were collected between June and August 2020.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was limited to completed questionnaires. The primary outcome of interest was the rate of psychological distress. Factors associated with psychological distress were analyzed using SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). The correlations between variables (including gender, age range, professional category, marital status, work experience, past history of physical and psychiatric ailments, and presence of a family member older than 70 years) with the desired outcome of interest were calculated. Continuous variables have been presented as median, whereas categorical variables are presented as percentage. Chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test, whichever was applicable, was applied for categorical variables. All tests are two sided and p < 0.05 is taken as the level of significance. Further, a multivariate analysis and logistic regression for distress was conducted using the forward conditional method.

Ethics Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Max Super Specialty Hospital, Saket, New Delhi, India (the protocol code was RS/MSSH/DDF/SKT-2/IEC/S-ONCO/20–13 and the date of approval was May 7, 2020).

Results

Response Rate and Respondents

Data were collected from a total of 87 HPs including 41 doctors, 28 nurses, and 18 support staff, comprising 34 males and 53 females, from the Department of Oncology across seven different units of MHC (Delhi-NCR, India). The median age of the participants was 32 years (range: 20–58 years). The demographic distribution and descriptive statistics of the study population are presented in [Table 1].

|

Variable |

Total |

Psychological distress |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

N = 87 |

No |

Yes |

p-Value |

|

|

Age range (y) |

||||

|

Above 35 |

29 |

89.70% |

10.30% |

0.229 |

|

Below 35 |

58 |

79.30% |

20.70% |

|

|

Gender |

||||

|

Female |

53 |

73.50% |

26.50% |

0.068 |

|

Male |

34 |

88.70% |

11.30% |

|

|

Marital status |

||||

|

Married |

57 |

82.50% |

17.50% |

0.918 |

|

Unmarried |

30 |

83.30% |

16.70% |

|

|

Professional category |

||||

|

Doctor |

41 |

80.50% |

19.50% |

0.871 |

|

Nurse |

28 |

82.10% |

17.90% |

|

|

Others |

18 |

88.90% |

11.10% |

|

|

Work experience (y) |

||||

|

< 10 |

56 |

75.00% |

25.00% |

0.017 |

|

> 10 |

31 |

96.70% |

3.30% |

|

|

Past history of physical ailment |

||||

|

No |

77 |

83.10% |

16.90% |

0.681 |

|

Yes |

10 |

80.00% |

20.00% |

|

|

Past history of psychiatric ailment |

||||

|

No |

82 |

86.60% |

13.40% |

0.003 |

|

Yes |

5 |

20.00% |

80.00% |

|

|

Family member above >70 y |

||||

|

No |

73 |

82.20% |

17.80% |

>0.999 |

|

Yes |

14 |

85.70% |

14.30% |

|

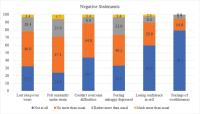

Fig 1:Components of psychological distress. Negative statements in the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12).

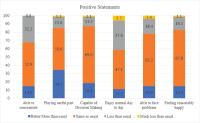

Fig 2:Components of psychological distress. Positive statements in the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-120.

Discussion

Our study offers an important understanding regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the psychological well-being of HPs working in the department of oncology in India. We used GHQ-12, which has been found to be reliable and valid[15] [16] and is one of the most commonly used tools to measure distress in HPs following viral outbreaks.[17] In our study, 17.20% of HPs showed the presence of psychological distress. It was also observed that HPs with a prior history of a psychiatric illness and having a work experience of less than 10 years reported significantly higher levels of psychological distress. There have been various systematic reviews in this area, most of which are from China, which estimate the prevalence of psychological distress among health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic to be between 13 and35%.[18] [19] [20] A study from India, which was part of an international collaborative effort examining the psychological distress among dentists in five countries, reported the overall prevalence of 12.6% with 12.2% among 470 Indian dentists. Existing literature also reports that the COVID-19 pandemic has had an impact on oncology professionals, indicating that 25% of participants (oncology professionals) in one study were at risk of distress (poor well-being).[21] The prevalence of psychological distress among our cohort of 87 HPs (17.20%) is consistent with these observations.

In some other studies, the prevalence of psychological distress was higher in comparison to the findings of this study. A study from India conducted a survey among 265 dental practitioners. The findings revealed that 30.18% participants showed the presence of moderate distress and 65.6% respondents indicated severe distress.[22] One literature review included 148 studies with 159,194 health care workers and pooled prevalence of various factors such as depression, anxiety, fear, burnout, low resilience, and stress. Here, stress was reported to be 36.4%.[23] Another follow-up study to one of the previously cited study[21] highlighted that 33% of the oncology professionals were at risk of poor well-being.[24] This suggests that there is an evident and accumulating effect on oncology HPs' mental health only after a few months of coping with the pandemic-related stress.[25] The study further underscored the long-term nature of the pandemic and its increased burden on oncology HPs, further suggesting long-term impact that requires attention and intervention, even after the recession of the pandemic.[25] Some possible reasons for this disparity with our study could be attributed to a larger sample size, period of study, and sampling methodology.

Based on studies on the psychological effects of previous virus outbreaks on health care workers, it was summarized that individual, health care service, and societal factors increase and decrease the risk of adverse psychological outcomes.[17] Multivariate logistic regression analysis of an online cross-sectional study reported that working in a public institution, being employed for less than 5 years, and being overworked were risk factors for developing psychological distress.[26] One study indicated that health care providers who reported to have depression and who reported to have used alcohol, tobacco, and khat in the past 3 months were more likely to experience psychological distress. This study further confirmed that there are increased odds of distress among respondents with underlying depression.[27] One study addressing the emotional concerns of oncology physicians based in the United States reported that anxiety and depression were related to the inability to provide adequate care to patients with cancer.[28] This observation was confirmed in our cohort where it was observed that HPs reporting a prior history of psychiatric illness (13.4%) and work experience of less than 10 years (25%) had a significantly higher prevalence of psychological distress. A limitation of our study was that we did not ask the participants to specify the type of their preexisting psychiatric illness, which would have potentially allowed us to further explore this association.

Due to the pandemic, many HPs were living away from families or were isolated due to the nature and exposure of their jobs. They also had reduced access to any form of domestic help, which further added a burden of maintaining a work–life balance. Many doctors have also faced salary cuts and other financial implications of the lockdown. Junior doctors and nurses (with lesser work experience) were posted in the COVID wards and units, which could have been an added stressor, thereby enhancing psychological distress. Few determinants that may justify these findings could be direct contact with affected patients, forced postings in the COVID wards, stigma against HPs in society, fear of passing on the infection to family members, and lack of training to use the PPE kits, among others, especially in the Indian health care setup.[29]

Other limitations of the study include that data were only collected via an online, self-reported questionnaire in the multivariable study design. It is likely that those with easy access to digital platforms and who are comfortable completing online surveys participated to a greater degree. Social distancing precluded us from distributing and collecting paper forms. The time taken in the design and approval of study allowed us to start collecting data from June 2020, which was approximately 3 months after the onset of the pandemic and the lockdown and may not be representative of the psychological distress experienced by HPs in the immediate days and weeks. Finally, the response rate was low, but our sample size is still comparable to similar studies from India.

Some of the implications of our findings focus on the urgency and the need for health care administrators, advocates, and policymakers to address the psychological well-being among HPs during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, and make mental health services easily accessible to them as and when required. There are recognized benefits of coordinated interprofessional team care and subsequently interprofessional education.[30] We created a channel of communication between our HPs and the in-house psychologists and psychiatrists for direct, easy, and free-of-cost access to mental health care. This was conducted through online, telephonic, and face-to-face mediums, and the HPs were given access to mental health professionals according to their comfort and convenience. Confidentiality was ensured and maintained throughout this process. It is suggested that this may be done by altering the assignments and schedules, modifying expectations, and creating mechanisms to offer psychosocial support as needed,[31] along with the addition of assessments of distress and related psychological factors to be implemented if and when the students or trainees are ascending to the frontline or health care setups.[32]

As a training domain, self-care is a spectrum of knowledge, skills, and attitudes including self-reflection and self-awareness, identification and prevention of burnout, appropriate professional boundaries, and grief and bereavement. Evidence indicates that medical HPs receive inadequate self-care training.[33] Some examples of professional self-care techniques can include developing a network of oncology professionals and peers who can share their concerns and techniques of effective coping, and pursuing reflective writing to allow self-expression and catharsis. Organizations can help formalize structures, policies, and procedures to guide team meetings and create a space for healthy and safe personal and professional sharing of sources. In a systematic review, it was reported that interventions conducted with HPs ranged from relaxation techniques, meditation, cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), mobile apps, music therapy, and exercise, to name a few.[34]

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Acknowledgments

We would like to recognize the efforts of Dr. Harit Chaturvedi and Dr. Sujeet Jha for their mentorship and Prof. Abhaya Indrayan for support with statistical analysis. We also want to thank Shailender Rathore, Sristi Raj, Ankit Kumar, and Arun Adhana from the Clinical Research Team.

Clinical Trial Registration

CTRI number: CTRI/2020/05/025220 (Registered on May 17, 2020); protocol code for Institutional Ethics Committee: RS/MSSH/DDF/SKT-2/IEC/S-ONCO/20–13; and date of approval: May 7, 2020.

References

- Que J, Shi L, Deng J. et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study in China. Gen Psychiatr 2020; 33 (03) e100259

- Pragholapati A. . Mental health in pandemic Covid-19. Available SSRN. 2020;3596311

- Kumar A, Nayar KR. COVID 19 and its mental health consequences. J Ment Health 2021; 30 (01) 1

- Vizheh M, Qorbani M, Arzaghi SM, Muhidin S, Javanmard Z, Esmaeili M. The mental health of healthcare workers in the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. J Diabetes Metab Disord 2020; 19 (02) 1967-1978

- Skoda EM, Teufel M, Stang A. et al. Psychological burden of healthcare professionals in Germany during the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: differences and similarities in the international context. J Public Health (Oxf) 2020; 42 (04) 688-695

- Thombs BD, Bonardi O, Rice DB. et al. Curating evidence on mental health during COVID-19: a living systematic review. J Psychosom Res 2020; 133: 110113

- De Kock JH, Latham HA, Leslie SJ. et al. A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers: implications for supporting psychological well-being. BMC Public Health 2021; 21 (01) 104

- Maciaszek J, Ciulkowicz M, Misiak B. et al. Mental health of medical and non-medical professionals during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional nationwide study. J Clin Med 2020; 9 (08) 2527

- Murthy RS. National mental health survey of India 2015–2016. Indian J Psychiatry 2017; 59 (01) 21-26

- Cullen W, Gulati G, Kelly BD. Mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic. QJM 2020; 113 (05) 311-312

- Roy A, Singh AK, Mishra S, Chinnadurai A, Mitra A, Bakshi O. Mental health implications of COVID-19 pandemic and its response in India. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2021; 67 (05) 587-600

- Ciammella P, De Bari B, Fiorentino A. et al; AIRO Giovani (Italian Association of Radiation Oncology-Young Members Working Group). The “BUONGIORNO” project: burnout syndrome among young Italian radiation oncologists. Cancer Invest 2013; 31 (08) 522-528

- Font A, Corti V, Berger R. Burnout in healthcare professionals in oncology. Procedia Econ Finance 2015; 23: 228-232

- Goldberg P, Williams P. A user's guide to the General Health Questionnaire. NFER-NELSON; 1988

- Machado T, Sathyanarayanan V, Bhola P, Kamath K. Psychological vulnerability, burnout, and coping among employees of a business process outsourcing organization. Ind Psychiatry J 2013; 22 (01) 26-31

- David BE, Kumar S. Psychological health problems during the lockdown: a survey of Indian population in COVID-19 pandemic. Data Brief 2020; 33: 106566

- Kisely S, Warren N, McMahon L, Dalais C, Henry I, Siskind D. Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020; 369: m1642

- Cénat JM, Blais-Rochette C, Kokou-Kpolou CK. et al. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 2021; 295: 113599

- Luo M, Guo L, Yu M, Jiang W, Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 2020; 291: 113190

- Salazar de Pablo G, Vaquerizo-Serrano J, Catalan A. et al. Impact of coronavirus syndromes on physical and mental health of health care workers: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2020; 275: 48-57

- Banerjee S, Lim KHJ, Murali K. et al. The impact of COVID-19 on oncology professionals: results of the ESMO Resilience Task Force survey collaboration. ESMO Open 2021; 6 (02) 100058

- Bagde R, Dandekeri S. Fear, stress and stigma of Covid-19 among Indian dental practitioners. J Evol Med Dent Sci 2021; 10 (31) 2433-2438

- Ching SM, Ng KY, Lee KW. et al. Psychological distress among healthcare providers during COVID-19 in Asia: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2021; 16 (10) e0257983

- Lim KHJ, Murali K, Kamposioras K. et al. The concerns of oncology professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: results from the ESMO Resilience Task Force survey II. ESMO Open 2021; 6 (04) 100199

- Granek L, Nakash O. Oncology healthcare professionals' mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Oncol 2022; 29 (06) 4054-4067

- Hossain MR, Patwary MM, Sultana R, Browning MHEM. Psychological distress among healthcare professionals during the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak in low resource settings: a cross-sectional study in Bangladesh. Front Public Health 2021; 9: 701920

- Hajure M, Dibaba B, Shemsu S, Desalegn D, Reshad M, Mohammedhussein M. Psychological distress among health care workers in health facilities of Mettu town during COVID-19 outbreak, South West Ethiopia, 2020. Front Psychiatry 2021; 12: 574671

- Thomaier L, Teoh D, Jewett P. et al. Emotional health concerns of oncology physicians in the United States: fallout during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One 2020; 15 (11) e0242767

- Wu P, Fang Y, Guan Z. et al. The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. Can J Psychiatry 2009; 54 (05) 302-311

- Aston SJ, Rheault W, Arenson C. et al. Interprofessional education: a review and analysis of programs from three academic health centers. Acad Med 2012; 87 (07) 949-955

- Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med 2020; 383 (06) 510-512

- Li Y, Wang Y, Jiang J. et al. Psychological distress among health professional students during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychol Med 2021; 51 (11) 1952-1954

- Sanchez-Reilly S, Morrison LJ, Carey E. et al. Caring for oneself to care for others: physicians and their self-care. J Support Oncol 2013; 11 (02) 75-81

- Robins-Browne K, Lewis M, Burchill LJ. et al. Interventions to support the mental health and well-being of front-line healthcare workers in hospitals during pandemics: an evidence review and synthesis. BMJ Open 2022; 12 (11) e061317

Address for correspondence

Publication History

Article published online:

17 April 2023

© 2023. The Author(s). This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, permitting unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction so long as the original work is properly cited. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

References

- Que J, Shi L, Deng J. et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study in China. Gen Psychiatr 2020; 33 (03) e100259

- Pragholapati A. . Mental health in pandemic Covid-19. Available SSRN. 2020;3596311

- Kumar A, Nayar KR. COVID 19 and its mental health consequences. J Ment Health 2021; 30 (01) 1

- Vizheh M, Qorbani M, Arzaghi SM, Muhidin S, Javanmard Z, Esmaeili M. The mental health of healthcare workers in the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. J Diabetes Metab Disord 2020; 19 (02) 1967-1978

- Skoda EM, Teufel M, Stang A. et al. Psychological burden of healthcare professionals in Germany during the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: differences and similarities in the international context. J Public Health (Oxf) 2020; 42 (04) 688-695

- Thombs BD, Bonardi O, Rice DB. et al. Curating evidence on mental health during COVID-19: a living systematic review. J Psychosom Res 2020; 133: 110113

- De Kock JH, Latham HA, Leslie SJ. et al. A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers: implications for supporting psychological well-being. BMC Public Health 2021; 21 (01) 104

- Maciaszek J, Ciulkowicz M, Misiak B. et al. Mental health of medical and non-medical professionals during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional nationwide study. J Clin Med 2020; 9 (08) 2527

- Murthy RS. National mental health survey of India 2015–2016. Indian J Psychiatry 2017; 59 (01) 21-26

- Cullen W, Gulati G, Kelly BD. Mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic. QJM 2020; 113 (05) 311-312

- Roy A, Singh AK, Mishra S, Chinnadurai A, Mitra A, Bakshi O. Mental health implications of COVID-19 pandemic and its response in India. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2021; 67 (05) 587-600

- Ciammella P, De Bari B, Fiorentino A. et al; AIRO Giovani (Italian Association of Radiation Oncology-Young Members Working Group). The “BUONGIORNO” project: burnout syndrome among young Italian radiation oncologists. Cancer Invest 2013; 31 (08) 522-528

- Font A, Corti V, Berger R. Burnout in healthcare professionals in oncology. Procedia Econ Finance 2015; 23: 228-232

- Goldberg P, Williams P. A user's guide to the General Health Questionnaire. NFER-NELSON; 1988

- Machado T, Sathyanarayanan V, Bhola P, Kamath K. Psychological vulnerability, burnout, and coping among employees of a business process outsourcing organization. Ind Psychiatry J 2013; 22 (01) 26-31

- David BE, Kumar S. Psychological health problems during the lockdown: a survey of Indian population in COVID-19 pandemic. Data Brief 2020; 33: 106566

- Kisely S, Warren N, McMahon L, Dalais C, Henry I, Siskind D. Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020; 369: m1642

- Cénat JM, Blais-Rochette C, Kokou-Kpolou CK. et al. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 2021; 295: 113599

- Luo M, Guo L, Yu M, Jiang W, Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 2020; 291: 113190

- Salazar de Pablo G, Vaquerizo-Serrano J, Catalan A. et al. Impact of coronavirus syndromes on physical and mental health of health care workers: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2020; 275: 48-57

- Banerjee S, Lim KHJ, Murali K. et al. The impact of COVID-19 on oncology professionals: results of the ESMO Resilience Task Force survey collaboration. ESMO Open 2021; 6 (02) 100058

- Bagde R, Dandekeri S. Fear, stress and stigma of Covid-19 among Indian dental practitioners. J Evol Med Dent Sci 2021; 10 (31) 2433-2438

- Ching SM, Ng KY, Lee KW. et al. Psychological distress among healthcare providers during COVID-19 in Asia: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2021; 16 (10) e0257983

- Lim KHJ, Murali K, Kamposioras K. et al. The concerns of oncology professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: results from the ESMO Resilience Task Force survey II. ESMO Open 2021; 6 (04) 100199

- Granek L, Nakash O. Oncology healthcare professionals' mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Oncol 2022; 29 (06) 4054-4067

- Hossain MR, Patwary MM, Sultana R, Browning MHEM. Psychological distress among healthcare professionals during the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak in low resource settings: a cross-sectional study in Bangladesh. Front Public Health 2021; 9: 701920

- Hajure M, Dibaba B, Shemsu S, Desalegn D, Reshad M, Mohammedhussein M. Psychological distress among health care workers in health facilities of Mettu town during COVID-19 outbreak, South West Ethiopia, 2020. Front Psychiatry 2021; 12: 574671

- Thomaier L, Teoh D, Jewett P. et al. Emotional health concerns of oncology physicians in the United States: fallout during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One 2020; 15 (11) e0242767

- Wu P, Fang Y, Guan Z. et al. The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. Can J Psychiatry 2009; 54 (05) 302-311

- Aston SJ, Rheault W, Arenson C. et al. Interprofessional education: a review and analysis of programs from three academic health centers. Acad Med 2012; 87 (07) 949-955

- Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med 2020; 383 (06) 510-512

- Li Y, Wang Y, Jiang J. et al. Psychological distress among health professional students during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychol Med 2021; 51 (11) 1952-1954

- Sanchez-Reilly S, Morrison LJ, Carey E. et al. Caring for oneself to care for others: physicians and their self-care. J Support Oncol 2013; 11 (02) 75-81

- Robins-Browne K, Lewis M, Burchill LJ. et al. Interventions to support the mental health and well-being of front-line healthcare workers in hospitals during pandemics: an evidence review and synthesis. BMJ Open 2022; 12 (11) e061317

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share