Imaging Recommendations for Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Soft Tissue Sarcomas

CC BY 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2023; 44(02): 261-267

DOI: DOI: 10.1055/s-0042-1760404

Abstract

Soft tissue lesions are a wide range of tumors of mesenchymal cell origin, occurring anywhere in the body with a vast number of histological subtypes both benign and malignant. These are common in clinical practice and vast majority are benign. This article focuses on soft tissue sarcoma of the trunk and extremities and discusses their imaging guidelines.

Publication History

Article published online:

01 March 2023

© 2023. The Author(s). This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, permitting unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction so long as the original work is properly cited. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Soft tissue lesions are a wide range of tumors of mesenchymal cell origin, occurring anywhere in the body with a vast number of histological subtypes both benign and malignant. These are common in clinical practice and vast majority are benign. This article focuses on soft tissue sarcoma of the trunk and extremities and discusses their imaging guidelines.

Introduction

Soft tissue sarcoma (STS) refers to a wide range of tumors of mesenchymal cell origin, occurring anywhere in the body with a vast number of histological subtypes both benign and malignant.[1] [Table 1] summarizes the main subtypes sarcoma that are comprehensively described by Bansal et al.[2] The study of STS is a constantly evolving field and regularly updated guidelines exist to summate the most up to date evidence providing a framework against which STS can be managed. This article will focus on imaging STS of the trunk and extremities and will not specifically address retroperitoneal sarcoma, aggressive fibromatosis, or neurofibromatosis.

|

Sarcoma subtype |

Benign |

Malignant |

|---|---|---|

|

Adipocytic |

Lipoma Lipoma variant |

Liposarcoma |

|

Fibroblastic and myofibroblastic |

Nodular fasciitis Elastofibroma |

Solitary fibrous tumor Myxofibrosarcoma Fibrosarcoma |

|

Fibrohistiocytic tumors |

Tenosynovial giant cell tumor |

Malignant tenosynovial giant cell tumor |

|

Vascular |

Hemangioma Epithelioid hemangioma |

Angiosarcoma Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma |

|

Pericytic |

Glomus tumor Angioleiomyoma |

Malignant glomus tumor |

|

Smooth muscle |

Leiomyoma |

Leiomyosarcoma |

|

Skeletal muscle |

Rhabdomyoma |

Rhabdomyosarcoma |

|

Tumors of uncertain differentiation |

Myxoma Angiomyolipoma |

Synovial sarcoma Alveolar soft part sarcoma Clear cell sarcoma Undifferentiated pleomorphic Sarcoma Undifferentiated spindle cell sarcoma |

|

Neural |

Schwannoma Neurofibroma |

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor |

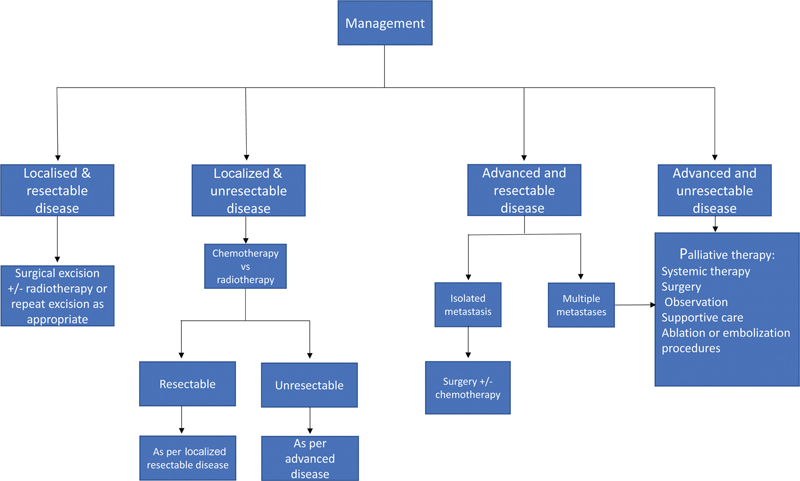

| Figure 1 A simplified referral pathway utilized by the authors institution in combination with relevant recommendations in the literature.

Imaging plays a central role in the workup of STS in terms of early diagnosis, through assessment of treatment response and monitoring for disease recurrence. The choice of initial investigation will depend on clinical factors including site of concern and examination findings. In general, investigation of the head, neck, mediastinum, and retroperitoneum is best served by computed tomography (CT), while ultrasound is considered the optimum initial investigation for clinically palpable lesions. This is reflected in several guidelines that recommended ultrasound as the initial investigation.[1] [2] [8] Plain radiographs also have a role in the workup particularly in lesions affecting the extremities. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is considered the gold standard investigation; however, its role as an initial investigation is not supported and instead it is used to further and more accurately characterize lesions.[2] [9]

Clinical/ Diagnostic work-up Excluding Imaging

The variable presentation of sarcoma coupled with its rarity and heterogeneity as a disease entity poses a diagnostic challenge for the clinician at the time of patient presentation. While almost all cases will require imaging to further investigate, it is important to remember that the vast majority will be benign.[1] [10] [11] A detailed clinical history and thorough clinical examination should therefore be performed to triage those cases in which there is a higher suspicion of malignancy. This will enable appropriate onward referral.[7] The clinical history should detail the site, pain symptoms, duration of lump, and any history of malignancy or previous surgery. Further information on the rate of growth and any associated symptoms should also be elucidated. Examination should confirm the size, depth, consistency, mobility, skin alterations, and presence of lesions elsewhere as well as confirm the presence or absence of tenderness. Clinical findings that raise the concern of malignancy include but are not limited to a size of more than 5cm, pain/tenderness, and lesion growth.[10] [11]

Imaging Guidelines

Screening

There is no specific screening program for STS. While in some conditions known to increase the risk—such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome—there may be specific individualized guidance in relation to the detection of malignancy; the broad aim is to encourage early presentation at the development of concerning symptoms.[4] [12]

Diagnosis

As already discussed, imaging is a fundamental component of patient workup for STS and essentially all patients will undergo some form of radiological investigation. The full range of modalities can be utilized, ranging from traditional plain film radiography to newer and less well-established techniques such as positron emission tomography/magnetic resonance imaging (PET/MRI). Imaging can be considered in terms of the advantages and disadvantages of the specific modality in question, the clinical presentation, and also the histological subtype of sarcoma that will determine the disease course.[2] [9] [13] Detailed below is a summary of the commonly used modalities and their role in the investigation of STS.

Plain radiographs are a cheap and widely available test that can be of use in the initial workup of a soft tissue lump—indeed the American College of Radiologists recommend them as part of the initial evaluation of a superficial lesion.[9] They are, however, limited by poor soft tissue contrast. For this reason, use is limited to the assessment of any relevant bony or mineralization changes at the site of concern (e.g., periosteal reaction, bony destruction). In certain situations, they may provide a diagnosis or significantly narrow the differential such as a lump corresponding to normal bony anatomy or reveal the presence of phleboliths indicating a hemangiomatous lesion.[14] [15]

Ultrasound has been shown to be an effective investigation for the initial evaluation of a soft tissue lump.[16] [17] In contrast to plain radiographs, ultrasound provides good soft tissue resolution and is a useful triage test to differentiate benign pathology such as simple lipomas, ganglion cysts, muscle hernias, and uncomplicated vascular malformations from more sinister lesions.[11] [17] The easy access of ultrasound to most primary care physicians has the advantage of providing patients reassurance and reducing the referral burden on local tertiary referral centers.[10] It is, however, limited by several factors, including but not limited to operator experience and patient body habitus. Location is also an important factor to consider as deeper lesions tend not to be easily amenable to assessment, particularly when a large geographical body area is required to be assessed. Similarly, bony lesions/bony involvement is not easily assessed.[17] [18]

MRI provides high spatial resolution, optimum soft tissue contrast, and allows accurate assessment of not just lesion size and morphology but also the relationship of the lesion to other structures (including local neurovasculature anatomy) enabling accurate local staging.[9] [13] Studies have assessed the utility of MRI in predicting the eventual grade of lesion and clinical outcome.[19] [20] [21] [22] [23] Crombé et al found that MRI features of tumor necrosis, heterogeneity, and peritumoral enhancement were associated with higher grade lesions. They also found that two or more of these features in combination were associated with a worse metastasis-free survival (MFS) as well as overall survival (OS). Interestingly, when the same principle of the presence of two or more of these features was applied to lower grade lesions (1 and 2), the MFS and OS were the same as for grade 3 lesions with the authors surmising that these MRI features could be used to predict prognosis on the baseline scan.[19] Other features that have been found to correlate with poor outcomes include lesion heterogeneity and size more than 10cm (in all STS subtypes) as well as features specific to individual sarcoma subtypes of which there are several. Scalas et al comprehensively describe several of these features which include the tail sign adjacent to the lesion in undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma and myxofibrosarcoma and the so-called triple sign in synovial sarcoma. This reflects the presence of low, intermediate, and high signal within the lesion. These features and others are summarized in [Table 2] along with their significance.[13] [20] [21] [24]

|

Sign |

Sarcoma subtype |

Significance |

|---|---|---|

|

Tail sign |

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, myxofibrosarcoma |

Higher risk of local recurrence and distant metastases at diagnosis |

|

Water like appearance |

Myxofibrosarcoma |

Increased likelihood of local recurrence with increasing percentage of water like signal within lesion |

|

Triple sign |

Synovial sarcoma |

Reduced disease-free survival |

|

Absence of calcifications |

Synovial sarcoma |

Reduced disease-free survival |

|

Signal heterogeneity |

Myxoid liposarcoma |

High-grade lesions and poorer prognosis |

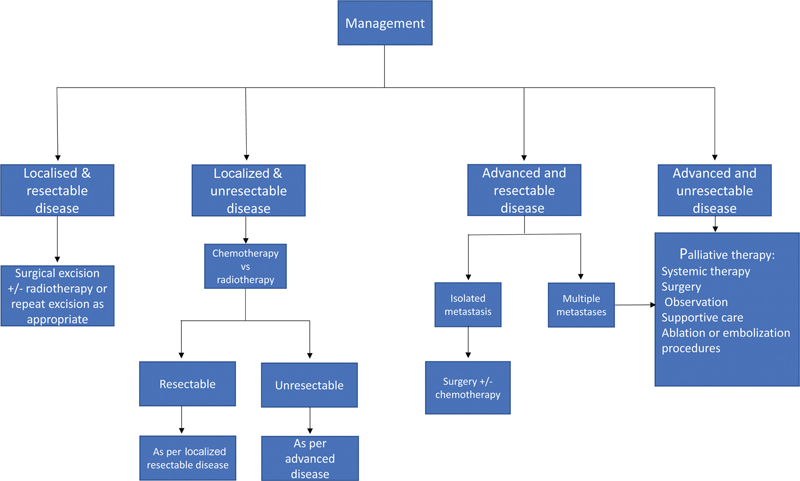

| Figure 1 Summarized flow chart showing the broad principles of management as per the UK, EU and US guidelines.

Summary of Recommendations

STS encompasses a heterogenous group of tumors making investigation and management a challenge.

All patients with a soft tissue lump more than 5cm, rapidly enlarging, or in any way suspicious of sarcoma should be referred for further investigation.

Ultrasound and plain radiographs are usual baseline tests often able to identify benign pathology and reassure patients.

MRI is the gold standard investigation and is best able to characterize the lesion with other investigations such as PET-CT utilized on a problem-solving basis.

The core theme of good sarcoma care is management through a dedicated multidisciplinary team meeting.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

- Dangoor A, Seddon B, Gerrand C, Grimer R, Whelan J, Judson I. UK guidelines for the management of soft tissue sarcomas. Clin Sarcoma Res 2016; 6 (01) 20

- Bansal A, Goyal S, Goyal A, Jana M. WHO classification of soft tissue tumours 2020: An update and simplified approach for radiologists. Eur J Radiol 2021; 143: 109937 DOI: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2021.109937.

- van Vliet M, Kliffen M, Krestin GP, van Dijke CF. Soft tissue sarcomas at a glance: clinical, histological, and MR imaging features of malignant extremity soft tissue tumors. Eur Radiol 2009; 19 (06) 1499-1511

- von Mehren M, Kane JM, Agulnik M. et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN guidelines ®). Soft Tissue Sarcoma. Version 2.2022 - 17/05/2022. NCCN.org. Accessed 23/05/2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/sarcoma.pdf

- PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Soft Tissue Sarcoma Treatment. Bethesda MD. National Cancer Institute. Updated 19/01/2022. Accessed December 23, 2022, at: http://www.cancer.gov/types/soft-tissue-sarcoma/hp/adult-soft-tissue-treatment-pdq

- Ilaslan H, Schils J, Nageotte W, Lietman SA, Sundaram M. Clinical presentation and imaging of bone and soft-tissue sarcomas. Cleve Clin J Med 2010; 77 (1, Suppl 1): S2-S7

- NICE has updated NICE Guideline 12, Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. Guidelines in Practice [Internet]. 2020 Oct [cited 2022 Jun 6];23(10):8. Accessed December 23, 2022, at:: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=edo&AN=146957423&site=eds-live

- Gronchi A, Miah AB, Dei Tos AP. et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee, EURACAN and GENTURIS. Electronic address: clinicalguidelines@esmo.org. Soft tissue and visceral sarcomas: ESMO-EURACAN-GENTURIS Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up☆ . Ann Oncol 2021; 32 (11) 1348-1365

- Kransdorf MJ, Murphey MD, Wessell DE. et al; Expert Panel on Musculoskeletal Imaging. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Soft-Tissue Masses. J Am Coll Radiol 2018; 15 (5S): S189-S197

- Bradley M, Robinson P, Gerrand C, Hayes A. et al. Ultrasound screening of soft tissue masses in the trunk and extremity. A British sarcoma group guide for ultrasonographers and primary care. British Sarcoma Group. January 2019. Accessed Dec 2022. https://britishsarcomagroup.org.uk/news/ultrasound-screening-of-soft-tissue-masses-in-the-trunk-and-extremity/

- Noebauer-Huhmann IM, Weber MA, Lalam RK. et al. Soft tissue tumors in adults: ESSR-approved guidelines for diagnostic imaging. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2015; 19 (05) 475-482

- American Cancer Society. Soft Tissue Sarcoma Early Detection, Diagnosis, and Staging [Internet]. Revised 06/04/2018. Cited 06/06/2022. Accessed December 23, 2022, at: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/soft-tissue-sarcoma/detection-diagnosis-staging/detection.html

- Scalas G, Parmeggiani A, Martella C. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of soft tissue sarcoma: features related to prognosis. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2021; 31 (08) 1567-1575

- Aga P, Singh R, Parihar A, Parashari U. Imaging spectrum in soft tissue sarcomas. Indian J Surg Oncol 2011; 2 (04) 271-279

- Gartner L, Pearce CJ, Saifuddin A. The role of the plain radiograph in the characterisation of soft tissue tumours. Skeletal Radiol 2009; 38 (06) 549-558 cited 2022Jun6 [Internet]

- Rowbotham E, Bhuva S, Gupta H, Robinson P. Assessment of referrals into the soft tissue sarcoma service: evaluation of imaging early in the pathway process. Sarcoma 2012; 2012: 781723

- Lakkaraju A, Sinha R, Garikipati R, Edward S, Robinson P. Ultrasound for initial evaluation and triage of clinically suspicious soft-tissue masses. Clin Radiol 2009; 64 (06) 615-621

- Singer AD, Wong P, Umpierrez M. et al. The accuracy of a novel sonographic scanning and reporting protocol to survey for soft tissue sarcoma local recurrence. Skeletal Radiol 2020; 49 (12) 2039-2049

- Crombé A, Marcellin PJ, Buy X. et al. Soft-tissue sarcomas: assessment of MRI features correlating with histologic grade and patient outcome. Radiology 2019; 291 (03) 710-721

- Spinnato P, Clinca R, Vara G. et al. MRI features as prognostic factors in myxofibrosarcoma: proposal of MRI grading system. Acad Radiol 2021; 28 (11) 1524-1529

- Yoo HJ, Hong SH, Kang Y. et al. MR imaging of myxofibrosarcoma and undifferentiated sarcoma with emphasis on tail sign; diagnostic and prognostic value. Eur Radiol 2014; 24 (08) 1749-1757

- Sambri A, Spinnato P, Bazzocchi A, Tuzzato GM, Donati D, Bianchi G. Does pre-operative MRI predict the risk of local recurrence in primary myxofibrosarcoma of the extremities?. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2019; 15 (05) e181-e186

- Tateishi U, Hasegawa T, Beppu Y, Satake M, Moriyama N. Synovial sarcoma of the soft tissues: prognostic significance of imaging features. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2004; 28 (01) 140-148

- Gimber LH, Montgomery EA, Morris CD, Krupinski EA, Fayad LM. MRI characteristics associated with high-grade myxoid liposarcoma. Clin Radiol 2017; 72 (07) 613.e1-613.e6

- Panicek DM, Gatsonis C, Rosenthal DI. et al. CT and MR imaging in the local staging of primary malignant musculoskeletal neoplasms: report of the Radiology Diagnostic Oncology Group. Radiology 1997; 202 (01) 237-246

- Sambri A, Bianchi G, Longhi A. et al. The role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in soft tissue sarcoma. Nucl Med Commun 2019; 40 (06) 626-631

- Bischoff M, Bischoff G, Buck A. et al. Integrated FDG-PET-CT: its role in the assessment of bone and soft tissue tumors. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2010; 130 (07) 819-827

- Shin DS, Shon OJ, Han DS, Choi JH, Chun KA, Cho IH. The clinical efficacy of (18)F-FDG-PET/CT in benign and malignant musculoskeletal tumors. Ann Nucl Med 2008; 22 (07) 603-609

- Lee L, Kazmer A, Colman MW, Gitelis S, Batus M, Blank AT. What is the clinical impact of staging and surveillance PET-CT scan findings in patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma?. J Surg Oncol 2022; 125 (05) 901-906

- Kassem TW, Abdelaziz O, Emad-Eldin S. Diagnostic value of 18F-FDG-PET/CT for the follow-up and restaging of soft tissue sarcomas in adults. Diagn Interv Imaging 2017; 98 (10) 693-698

- Seeger LL. Revisiting Tract Seeding and Compartmental Anatomy for Percutaneous Image-Guided Musculoskeletal Biopsies. Vol. 48, Skeletal Radiology. Springer Verlag; 2019: 499-501

- Veltri A, Bargellini I, Giorgi L, Almeida PAMS, Akhan O. CIRSE guidelines on percutaneous needle biopsy (PNB). Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2017; 40 (10) 1501-1513

- Cates JMM. The AJCC 8th edition staging system for soft tissue sarcoma of the extremities or trunk: a cohort study of the SEER database. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2018; 16 (02) 144-152 cited 2022Jun7 [Internet]

- Rothermundt C, Whelan JS, Dileo P. et al. What is the role of routine follow-up for localised limb soft tissue sarcomas? A retrospective analysis of 174 patients. Br J Cancer 2014; 110 (10) 2420-2426

- Hovgaard TB, Nymark T, Skov O, Petersen MM. Follow-up after initial surgical treatment of soft tissue sarcomas in the extremities and trunk wall. Acta Oncol 2017; 56 (07) 1004-1012

- Park JW, Yoo HJ, Kim HS. et al. MRI surveillance for local recurrence in extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2019; 45 (02) 268-274

- Puri A, Gulia A, Hawaldar R, Ranganathan P, Badwe RA. Does intensity of surveillance affect survival after surgery for sarcomas? Results of a randomized noninferiority trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472 (05) 1568-1575

Address for correspondence

Publication History

Article published online:

01 March 2023

© 2023. The Author(s). This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, permitting unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction so long as the original work is properly cited. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

| Figure 1 A simplified referral pathway utilized by the authors institution in combination with relevant recommendations in the literature.

| Figure 1 Summarized flow chart showing the broad principles of management as per the UK, EU and US guidelines.

- Dangoor A, Seddon B, Gerrand C, Grimer R, Whelan J, Judson I. UK guidelines for the management of soft tissue sarcomas. Clin Sarcoma Res 2016; 6 (01) 20

- Bansal A, Goyal S, Goyal A, Jana M. WHO classification of soft tissue tumours 2020: An update and simplified approach for radiologists. Eur J Radiol 2021; 143: 109937 DOI: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2021.109937.

- van Vliet M, Kliffen M, Krestin GP, van Dijke CF. Soft tissue sarcomas at a glance: clinical, histological, and MR imaging features of malignant extremity soft tissue tumors. Eur Radiol 2009; 19 (06) 1499-1511

- von Mehren M, Kane JM, Agulnik M. et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN guidelines ®). Soft Tissue Sarcoma. Version 2.2022 - 17/05/2022. NCCN.org. Accessed 23/05/2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/sarcoma.pdf

- PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Soft Tissue Sarcoma Treatment. Bethesda MD. National Cancer Institute. Updated 19/01/2022. Accessed December 23, 2022, at: http://www.cancer.gov/types/soft-tissue-sarcoma/hp/adult-soft-tissue-treatment-pdq

- Ilaslan H, Schils J, Nageotte W, Lietman SA, Sundaram M. Clinical presentation and imaging of bone and soft-tissue sarcomas. Cleve Clin J Med 2010; 77 (1, Suppl 1): S2-S7

- NICE has updated NICE Guideline 12, Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. Guidelines in Practice [Internet]. 2020 Oct [cited 2022 Jun 6];23(10):8. Accessed December 23, 2022, at:: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=edo&AN=146957423&site=eds-live

- Gronchi A, Miah AB, Dei Tos AP. et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee, EURACAN and GENTURIS. Electronic address: clinicalguidelines@esmo.org. Soft tissue and visceral sarcomas: ESMO-EURACAN-GENTURIS Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up☆ . Ann Oncol 2021; 32 (11) 1348-1365

- Kransdorf MJ, Murphey MD, Wessell DE. et al; Expert Panel on Musculoskeletal Imaging. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Soft-Tissue Masses. J Am Coll Radiol 2018; 15 (5S): S189-S197

- Bradley M, Robinson P, Gerrand C, Hayes A. et al. Ultrasound screening of soft tissue masses in the trunk and extremity. A British sarcoma group guide for ultrasonographers and primary care. British Sarcoma Group. January 2019. Accessed Dec 2022. https://britishsarcomagroup.org.uk/news/ultrasound-screening-of-soft-tissue-masses-in-the-trunk-and-extremity/

- Noebauer-Huhmann IM, Weber MA, Lalam RK. et al. Soft tissue tumors in adults: ESSR-approved guidelines for diagnostic imaging. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2015; 19 (05) 475-482

- American Cancer Society. Soft Tissue Sarcoma Early Detection, Diagnosis, and Staging [Internet]. Revised 06/04/2018. Cited 06/06/2022. Accessed December 23, 2022, at: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/soft-tissue-sarcoma/detection-diagnosis-staging/detection.html

- Scalas G, Parmeggiani A, Martella C. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of soft tissue sarcoma: features related to prognosis. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2021; 31 (08) 1567-1575

- Aga P, Singh R, Parihar A, Parashari U. Imaging spectrum in soft tissue sarcomas. Indian J Surg Oncol 2011; 2 (04) 271-279

- Gartner L, Pearce CJ, Saifuddin A. The role of the plain radiograph in the characterisation of soft tissue tumours. Skeletal Radiol 2009; 38 (06) 549-558 cited 2022Jun6 [Internet]

- Rowbotham E, Bhuva S, Gupta H, Robinson P. Assessment of referrals into the soft tissue sarcoma service: evaluation of imaging early in the pathway process. Sarcoma 2012; 2012: 781723

- Lakkaraju A, Sinha R, Garikipati R, Edward S, Robinson P. Ultrasound for initial evaluation and triage of clinically suspicious soft-tissue masses. Clin Radiol 2009; 64 (06) 615-621

- Singer AD, Wong P, Umpierrez M. et al. The accuracy of a novel sonographic scanning and reporting protocol to survey for soft tissue sarcoma local recurrence. Skeletal Radiol 2020; 49 (12) 2039-2049

- Crombé A, Marcellin PJ, Buy X. et al. Soft-tissue sarcomas: assessment of MRI features correlating with histologic grade and patient outcome. Radiology 2019; 291 (03) 710-721

- Spinnato P, Clinca R, Vara G. et al. MRI features as prognostic factors in myxofibrosarcoma: proposal of MRI grading system. Acad Radiol 2021; 28 (11) 1524-1529

- Yoo HJ, Hong SH, Kang Y. et al. MR imaging of myxofibrosarcoma and undifferentiated sarcoma with emphasis on tail sign; diagnostic and prognostic value. Eur Radiol 2014; 24 (08) 1749-1757

- Sambri A, Spinnato P, Bazzocchi A, Tuzzato GM, Donati D, Bianchi G. Does pre-operative MRI predict the risk of local recurrence in primary myxofibrosarcoma of the extremities?. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2019; 15 (05) e181-e186

- Tateishi U, Hasegawa T, Beppu Y, Satake M, Moriyama N. Synovial sarcoma of the soft tissues: prognostic significance of imaging features. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2004; 28 (01) 140-148

- Gimber LH, Montgomery EA, Morris CD, Krupinski EA, Fayad LM. MRI characteristics associated with high-grade myxoid liposarcoma. Clin Radiol 2017; 72 (07) 613.e1-613.e6

- Panicek DM, Gatsonis C, Rosenthal DI. et al. CT and MR imaging in the local staging of primary malignant musculoskeletal neoplasms: report of the Radiology Diagnostic Oncology Group. Radiology 1997; 202 (01) 237-246

- Sambri A, Bianchi G, Longhi A. et al. The role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in soft tissue sarcoma. Nucl Med Commun 2019; 40 (06) 626-631

- Bischoff M, Bischoff G, Buck A. et al. Integrated FDG-PET-CT: its role in the assessment of bone and soft tissue tumors. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2010; 130 (07) 819-827

- Shin DS, Shon OJ, Han DS, Choi JH, Chun KA, Cho IH. The clinical efficacy of (18)F-FDG-PET/CT in benign and malignant musculoskeletal tumors. Ann Nucl Med 2008; 22 (07) 603-609

- Lee L, Kazmer A, Colman MW, Gitelis S, Batus M, Blank AT. What is the clinical impact of staging and surveillance PET-CT scan findings in patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma?. J Surg Oncol 2022; 125 (05) 901-906

- Kassem TW, Abdelaziz O, Emad-Eldin S. Diagnostic value of 18F-FDG-PET/CT for the follow-up and restaging of soft tissue sarcomas in adults. Diagn Interv Imaging 2017; 98 (10) 693-698

- Seeger LL. Revisiting Tract Seeding and Compartmental Anatomy for Percutaneous Image-Guided Musculoskeletal Biopsies. Vol. 48, Skeletal Radiology. Springer Verlag; 2019: 499-501

- Veltri A, Bargellini I, Giorgi L, Almeida PAMS, Akhan O. CIRSE guidelines on percutaneous needle biopsy (PNB). Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2017; 40 (10) 1501-1513

- Cates JMM. The AJCC 8th edition staging system for soft tissue sarcoma of the extremities or trunk: a cohort study of the SEER database. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2018; 16 (02) 144-152 cited 2022Jun7 [Internet]

- Rothermundt C, Whelan JS, Dileo P. et al. What is the role of routine follow-up for localised limb soft tissue sarcomas? A retrospective analysis of 174 patients. Br J Cancer 2014; 110 (10) 2420-2426

- Hovgaard TB, Nymark T, Skov O, Petersen MM. Follow-up after initial surgical treatment of soft tissue sarcomas in the extremities and trunk wall. Acta Oncol 2017; 56 (07) 1004-1012

- Park JW, Yoo HJ, Kim HS. et al. MRI surveillance for local recurrence in extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2019; 45 (02) 268-274

- Puri A, Gulia A, Hawaldar R, Ranganathan P, Badwe RA. Does intensity of surveillance affect survival after surgery for sarcomas? Results of a randomized noninferiority trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472 (05) 1568-1575

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share