How We Use Immunohistochemistry to Arrive at a Diagnosis in Breast Lesions

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2022; 43(01): 114-119

DOI: DOI: 10.1055/s-0042-1742439

Abstract

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is an essential tool available to pathologists for facilitating diagnosis and as well as guiding the prognosis of breast lesions. Newer markers are increasingly being added to the pathologists' armamentarium. However, the selection and interpretation of the IHC markers should be judicious. In light of an appropriate morphological assessment, they should complement each other and produce accurate reports. We have briefly outlined here the immunohistochemical approach used in the diagnosis and management of breast cancers at our tertiary care cancer center.

Authors' Contributions

AS was involved in conceptualization, designing, intellectual content, literature search, manuscript preparation, editing and review. SBD and AP contributed substantially in designing, intellectual content, manuscript editing and review.

Publication History

Article published online:

14 February 2022

© 2022. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is an essential tool available to pathologists for facilitating diagnosis and as well as guiding the prognosis of breast lesions. Newer markers are increasingly being added to the pathologists' armamentarium. However, the selection and interpretation of the IHC markers should be judicious. In light of an appropriate morphological assessment, they should complement each other and produce accurate reports. We have briefly outlined here the immunohistochemical approach used in the diagnosis and management of breast cancers at our tertiary care cancer center.

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most common cancers affecting females worldwide and in India.[1] [2] Although morphological features of breast lesions are well described, immunohistochemical evaluation forms an indispensable component of not only accurate diagnosis but also a prognostic and predictive ancillary tool for breast cancer pathologists. At our high-volume tertiary care cancer center, breast lesions routinely undergo such diagnostic and prognostic evaluation and we briefly outline below our immunohistochemical approach for the different types of lesions encountered.

For diagnosis, appropriate immunohistochemistry (IHC) marker panel is ideally selected in view of the morphological features to address a specific diagnostic query. Prognostic IHC panels, on the other hand, are applied routinely in pathologically (morphologically and/or immunohistochemically) confirmed malignancies for guiding treatment decisions.

Diagnostic IHC

-

A) Benign versus Malignant?

This is the first and foremost question a pathologist has to answer when viewing a breast biopsy or specimen. Several benign lesions (such as complex sclerosing lesions and radial scar) and in situ tumors can mimic invasive tumors. In the breast, the hallmark of invasion is lack of myoepithelial cells (MECs).[3] Both benign and in situ lesions show presence of an intact myoepithelial layer (albeit sometimes discontinuous) and basement membrane around the breast ducts and acini. However, MECs may not always be appreciable on morphology and there are a number of IHC markers available for their identification such as p63, p40, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (SMMHC), calponin, smooth muscle antigen (SMA), S100, CD10, CK5/6. The absence of staining for MECs indicates invasive cancer. A notable exception is microglandular adenosis that is a benign lesion but lacks MECs; however, it is identifiable by immunoreactivity for S100 protein and is typically triple negative. Conversely, adenoid cystic carcinoma and metaplastic carcinoma may be positive for MEC markers; however, the location of positivity will not be peripheral or linear.[4] Various MEC markers and their utilities are shown in [Table 1]. In our practice, we use a combination of at least one nuclear (usually p63) and one cytoplasmic MEC marker (usually calponin or SMMHC). Other markers like SMA and S100 show a lot of cross-reactivity with surrounding myofibroblasts (especially in desmoplastic stroma) and blood vessels, limiting interpretation. Importantly, caution should be exercised when evaluating MEC markers in poorly fixed tissue and the presence of internal positive control (adjacent benign ducts) should always be cross-checked before interpreting MEC markers as absent to avoid a false-positive diagnosis of carcinoma.

|

Marker |

Pattern |

Utility |

Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|

|

P63 |

Nuclear |

Best MEC marker with a clean background, no cross-reactivity with stromal myofibroblasts or vascular smooth muscle cells. Highly specific and ∼90% sensitive |

May show focal gaps/attenuation (discontinuous pattern) around noninvasive epithelial nests (especially CIS) and may also label ACC, papillary Ca, and squamous component of metaplastic Ca in a diffuse fashion |

|

P40 |

Nuclear |

Antibody against an isoform of p63, with similar reactivity and performance |

Same as above. May be used interchangeably, but not proven superior to p63 for breast MEC |

|

SMMHC |

Cytoplasmic |

Slightly higher sensitivity than p63 |

Cross-reactivity with stromal myofibroblasts and vascular smooth muscle |

|

Calponin |

Cytoplasmic |

Continuous cytoplasmic linear staining pattern in normal or benign breast tissue, with a focal discontinuous pattern in a few DCIS |

A high frequency of cross-reactivity with stromal myofibroblasts and vascular smooth muscle cells as well as occasionally tumor epithelial cells |

|

CD10 |

Cytoplasmic |

Relatively sensitive, no reactivity to vascular smooth muscle cells |

Cross-reactivity to myofibroblasts and nonspecific reactivity to epithelial cells |

|

CK 5/6 |

Cytoplasmic |

Identifies MEC as well as useful in benign ductal hyperplasia and papillary breast lesions (usually mosaic) to differentiate from DCIS (usually negative) |

Also positive in squamous epithelial cells, basal subtype DCIS and basal-like TNBC |

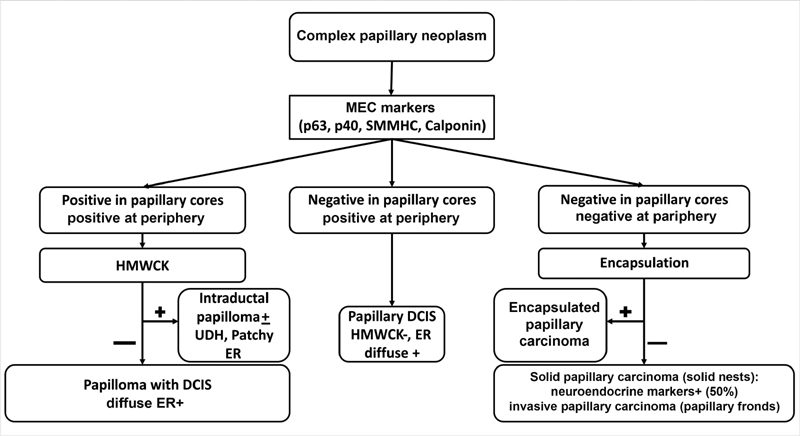

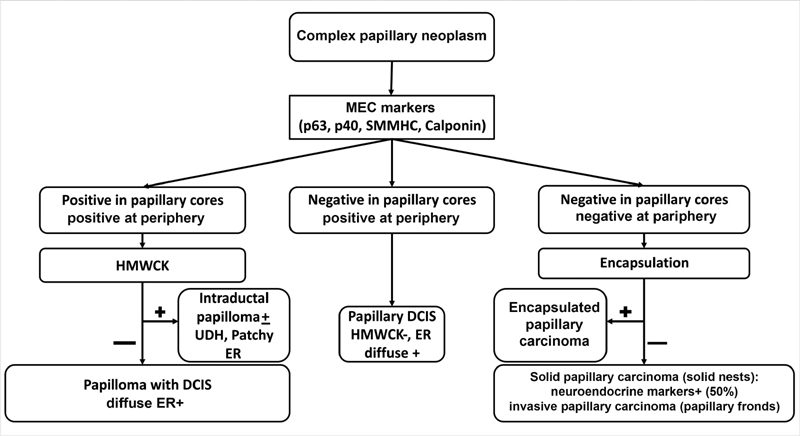

| Fig. 1Stepwise combined morphological and immunohistochemistry approach to the diagnosis of complex papillary neoplasms of breast. DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; ER, estrogen receptor; HMWCK, high molecular weight keratins; MEC, myoepithelial cells; SMMHC, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain; UDH, usual ductal hyperplasia.

-

E) Diagnosis of spindle cell neoplasms (SCN)?

SCN of the breast encompasses a wide spectrum ranging from benign to malignant and epithelial to myoepithelial to mesenchymal in origin. Biopsy interpretation of SCN of the breast is especially challenging due to limited tissue. It is helpful to categorize the lesion as low-grade or high-grade on initial screening, consider the various differentials of each category, and accordingly choose IHC markers.[8] [9] In high-grade SCN, a differentiation between metaplastic or metastatic carcinoma from primary high-grade sarcoma or malignant phyllodes is particularly poignant due to differences in management, with nodal evaluation and chemotherapy more common for the former rather than latter.[3] [8] No specific IHC is useful to distinguish different grades of phyllodes tumor. [Table 2] summarizes our diagnostic approach for high-grade and low-grade SCN. Morphological clues are often helpful, particularly the presence or absence of benign ducts or in situ carcinoma. Usually, a panel of markers is selected in light of morphology; however, if uncertainty persists even after morphological and immunohistochemical evaluation on a core biopsy, it is acceptable to exercise caution and issue a preliminary report of “low- grade SCN” or “high-grade SCN” and defer a definitive categorization for the subsequent surgical specimen.

|

Spindle cell neoplasm |

Entity |

Morphological clues |

Immunohistochemistry |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Positive |

Negative |

|||

|

Low-grade |

Myofibroblastoma |

Bland spindle cells with thick collagen bundles, devoid of mammary ducts |

CD34, desmin, variable: SMA, EMA, ER, PR, CD99, BCl2, CD10, S100 |

Epithelial markers (AE1/AE3, Pan-CK) |

|

Fibromatosis |

Bland spindle cells, collagenous stroma; infiltrative border with chronic inflammation |

Diffuse nuclear b-catenin, SMA, desmin ± |

S100, CD34, epithelial markers |

|

|

Fibromatosis-like metaplastic carcinoma |

Spindle cells with tapered nuclei, nuclear atypia and mitosis not prominent; DCIS rare (10–15%) |

Epithelial markers (AE1/AE3, pan-CK, or HMWCK), p63, SMA |

Desmin, CD34, BCl2, ER, PR, Her2 |

|

|

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans |

Dermal; spindle cells in storiform and whirling pattern; infiltrative edges |

CD34, SMA ± |

S100, epithelial markers, factor XIIIa |

|

|

PASH |

Sclerotic stroma; slit-like spaces lined by bland myofibroblastic cells, resembling endothelial cells |

CD34, Bcl2, SMA, PR |

CD31, ERG, desmin, ER |

|

|

Nodular fasciitis |

Loose edematous stroma; mitosis usual; extravasated RBCs; inflammatory cells |

SMA |

Desmin, S100, CD34, epithelial markers |

|

|

High grade |

Metaplastic carcinoma |

Malignant in situ/invasive epithelial component—helpful if present |

Cytokeratin (AE1/AE3/Pan CK/EMA), SMA ± |

CD34, S100, HMB45, |

|

Malignant phyllodes tumor |

Any benign epithelial component—helpful if present |

CD34 (30-50%), BCl2, C-kit, SMA ± , CK (rare), p63 (rare) |

S100, HMB45 |

|

|

Sarcoma |

Any specific lineage differentiation (myoid, vascular, adipocytic, etc.) if present |

As per lineage differentiation |

CK, HMB45 |

|

|

Melanoma |

Intracytoplasmic pigment (if present), vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli |

S100, HMB45, Melan A |

CK, EMA, CD34 |

|

| Fig. 1Stepwise combined morphological and immunohistochemistry approach to the diagnosis of complex papillary neoplasms of breast. DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; ER, estrogen receptor; HMWCK, high molecular weight keratins; MEC, myoepithelial cells; SMMHC, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain; UDH, usual ductal hyperplasia.

References

- Nair N, Shet T, Parmar V. et al. Breast cancer in a tertiary cancer center in India - an audit, with outcome analysis. Indian J Cancer 2018; 55 (01) 16-22

- Rangarajan B, Shet T, Wadasadawala T. et al. Breast cancer: an overview of published Indian data. South Asian J Cancer 2016; 5 (03) 86-92

- Liu H. Application of immunohistochemistry in breast pathology: a review and update. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2014; 138 (12) 1629-1642

- Peng Y, Butt YM, Chen B, Zhang X, Tang P. Update on immunohistochemical analysis in breast lesions. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2017; 141 (08) 1033-1051

- Zaha DC. Significance of immunohistochemistry in breast cancer. World J Clin Oncol 2014; 5 (03) 382-392

- Jorns JM. Papillary lesions of the breast: a practical approach to diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2016; 140 (10) 1052-1059

- Varga Z, Mallon E. Histology and immunophenotype of invasive lobular breast cancer. daily practice and pitfalls. Breast Dis 2008-2009–2009; 30: 15-19

- Tse GM, Ni YB, Tsang JY. et al. Immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of papillary lesions of the breast. Histopathology 2014; 65 (06) 839-853

- Tay TKY, Tan PH. Spindle cell lesions of the breast - an approach to diagnosis. Semin Diagn Pathol 2017; 34 (05) 400-409

- Rakha EA, Aleskandarany MA, Lee AH, Ellis IO. An approach to the diagnosis of spindle cell lesions of the breast. Histopathology 2016; 68 (01) 33-44

- Allison KH, Hammond MEH, Dowsett M. et al. Estrogen and progesterone receptor testing in breast cancer: ASCO/CAP guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2020; 38 (12) 1346-1366

- Wolff AC, Hammond MEH, Allison KH. et al. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists Clinical Practice Guideline focused update. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36 (20) 2105-2122

- Nielsen TO, Leung SCY, Rimm DL. et al. Assessment of Ki67 in breast cancer: updated recommendations from the International Ki67 in Breast Cancer Working Group. J Natl Cancer Inst 2021; 113 (07) 808-819

- Goldhirsch A, Winer EP, Coates AS. et al; Panel members. Personalizing the treatment of women with early breast cancer: highlights of the St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2013. Ann Oncol 2013; 24 (09) 2206-2223

- Cimino-Mathews A. Novel uses of immunohistochemistry in breast pathology: interpretation and pitfalls. Mod Pathol 2021; 34 (Suppl. 01) 62-77

- Schmid P, Adams S, Rugo HS. et al; IMpassion130 Trial Investigators. Atezolizumab and nab-paclitaxel in advanced triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2018; 379 (22) 2108-2121

- Desai SB. Breast cancer pathology reporting in the Indian context: need for introspection. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2020; 63 (Supplement): S3-S4

- Shet T. Ki-67 in breast cancer: simulacra and simulation. Indian J Cancer 2020; 57 (03) 231-233

- Shet T. Improving accuracy of breast cancer biomarker testing in India. Indian J Med Res 2017; 146 (04) 449-458

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share