How pseudo is an inflammatory pseudotumor?

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2011; 32(04): 204-206

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/0971-5851.95141

Abstract

Inflammatory pseudotumor (IPT) is a rare lesion of unclear etiology reported in various organs. Although mostly benign, these tumors may pose a therapeutic challenge in cases of recurrence. We report the case of a young male who presented with a clinical and radiological picture suggestive of a malignancy in the thorax and upon evaluation was noted to have IPT of the lung. Complete surgical resection was done with no evidence of tumor recurrence. We review the literature and discern the epidemiological, clinical, pathophysiological and management aspects of IPTs.

Publication History

Article published online:

06 August 2021

© 2011. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Inflammatory pseudotumor (IPT) is a rare lesion of unclear etiology reported in various organs. Although mostly benign, these tumors may pose a therapeutic challenge in cases of recurrence. We report the case of a young male who presented with a clinical and radiological picture suggestive of a malignancy in the thorax and upon evaluation was noted to have IPT of the lung. Complete surgical resection was done with no evidence of tumor recurrence. We review the literature and discern the epidemiological, clinical, pathophysiological and management aspects of IPTs.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory pseudotumors (IPTs) are rare, well-circumscribed, unencapsulated, quasi-neoplastic tumors of unregulated growth of inflammatory cells, first recognized by Umiker and Iverson.[1] Various terms have been used to describe them based on the predominance of the particular type of cytology, such as plasma cell granuloma, plasma cell pseudotumor, inflammatory myofibroblastic proliferation, omental-mesenteric hamartoma, histiocytoma and fibroxanthoma. It can roughly be categorized into an organizing pneumonia pattern, a fibrous histiocytic pattern (most common) and a lymphohistiocytic pattern (least common).[2] It is not yet established if these lesions represent a primary inflammatory process or a low-grade malignancy with a prominent inflammatory response.

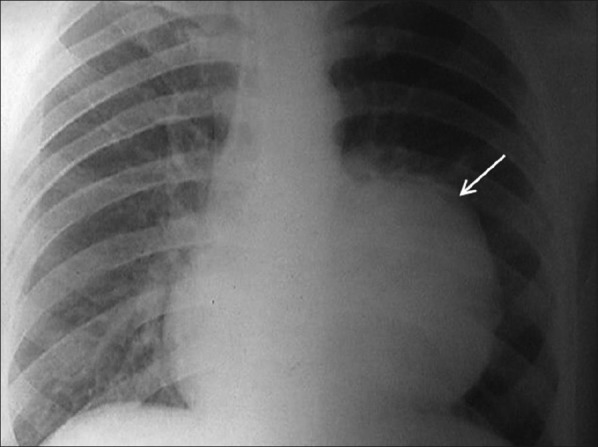

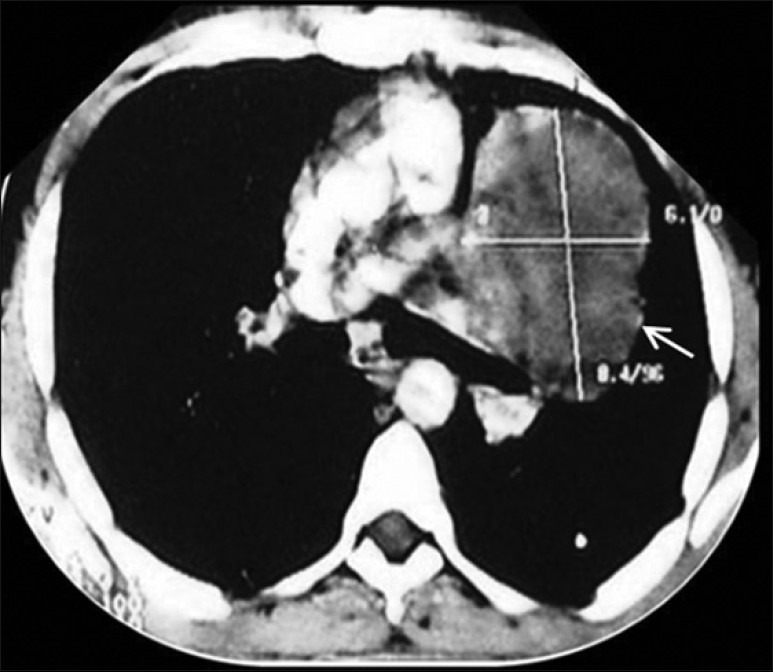

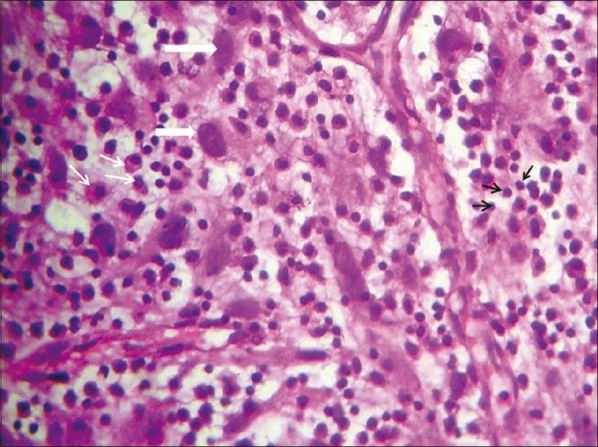

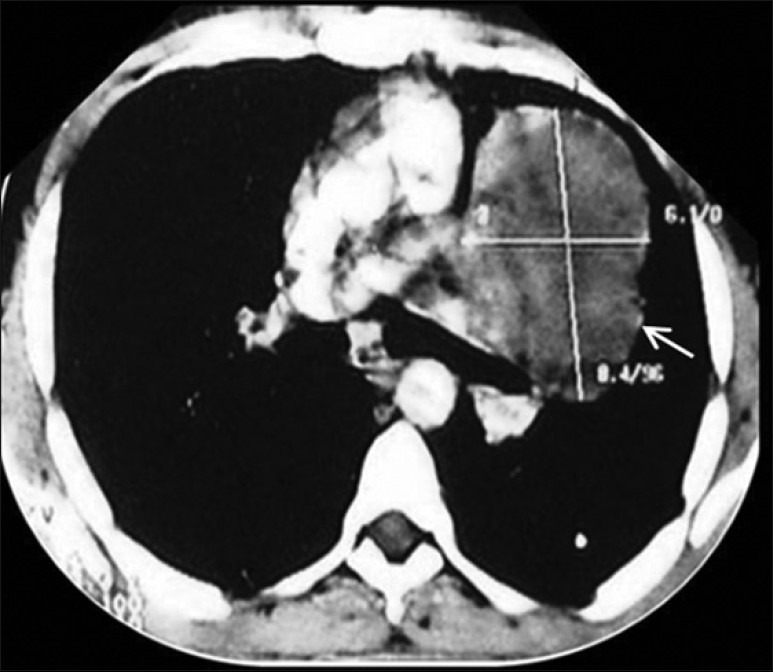

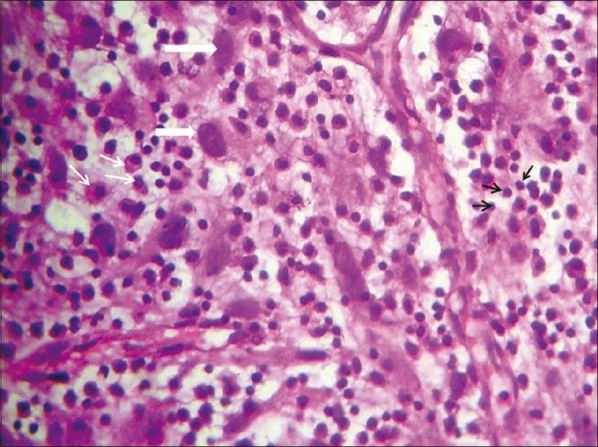

We report a case of a 33-year-old male who presented with a history of cough with productive sputum, shortness of breath, recurrent fever (low grade), generalized weakness, anorexia and weight loss of 6 months duration. He also had an episode of hemoptysis. He was a non-smoker and worked as a clerical assistant at an office (no occupational exposure to potential allergens or toxic agents). On examination, he was thin built, and had pallor and clubbing. An impaired percussion note and decreased breath sounds were found on the left. Lab investigations revealed high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR; 55 mm/hour), anemia (Hb 8 g/dl), and thrombocytosis (580,000). X-ray chest revealed a large lobulated soft tissue mass lesion overlying the left cardiac border, situated in anterior and middle mediastinum [Figure 1]. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) thorax showed a hypodense mass lesion, measuring 8.4 × 6.1 cm, adjacent to left hilum without any evidence of calcification or contrast enhancement [Figure 2]. Radiological differential diagnosis was that of hydatid cyst, empyema or neoplasm. Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) was done which was inconclusive (no malignant cells). Patient was taken up for thoracotomy and a large mass, measuring 8 and 10 cm, arising from the lower lobe of left lung adherent to pericardium and diaphragm without a definite plane of cleavage was found. The necrotic mass was excised. Grossly, the specimen was lobular with a rubbery tan-yellow cut surface. Histopathology showed bland spindle-/stellate-shaped myofibroblasts loosely arranged in a myxoid stroma with scattered plasma cells and inflammatory cells [Figure 3]. There were varying mitoses, prominent lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and a few germinal centers. The immune profile of the specimen was positive for smooth muscle actin, strongly positive for vimentin, negative for desmin and equivocal for epithelial membrane antigen. Final diagnosis of IPT of the left lung was made. The patient had been doing well and a follow-up of 2 years showed no evidence of tumor recurrence. There was a feeling of well-being with acceptable weight gain (5 kg), and no further cough, shortness of breath or fever was reported.

| Figure 1:Chest radiograph showing a large lobulated soft tissue mass lesion overlying the left cardiac border, situated in anterior and middle mediastinum

| Figure 2:Contrast-enhanced CT thorax showing a hypodense mass lesion measuring 8.4 × 6.1 cm adjacent to left hilum without any evidence of calcification or contrast enhancement

| Figure 3:High-power view showing myofibroblasts with plump oval nuclei (thick white arrows), plasma cells (thin white arrows) and inflammatory cells, mainly lymphocytes (black arrows) in a collagenous background with myxoid areas and proliferating vessels

DISCUSSION

Though IPTs of the lung are rare (0.04–0.7% incidence of all lung masses[3] ), they pose a diagnostic and/or therapeutic challenge to the managing team of clinicians, pathologists, and surgeons. IPT is a distinctive pseudosarcomatous lesion occurring primarily in the viscera and soft tissues. It is seen mostly in children and young adults (half of the patients are less than 40 years[4]) with an equal sex distribution. Although initially reported and is more common in the lung, it has a propensity to involve the orbit, stomach, testis, esophagus, liver, spleen, pancreas, kidney, adrenal gland, retroperitoneum, diaphragm, mesentery, bladder, heart, thyroid, tonsil, fourth ventricle, spinal cord meninges, central nervous system, maxillary sinus, nasopharynx, larynx and trachea.[5] Two other notable cases of IPT have been reported from India, a 12-year-old presenting with massive hemoptysis[6] and a 3.5-year-old initially misdiagnosed to have a neuroblastoma.[7] Another 78-year-old developed a metachronous lung IPT, 7 years after having an orbital IPT.[8] WHO has recently classified the lesions into myxoid vascular, compact spindle cell, and hypocellular fibrous patterns with varying degrees of overlap within a lesion. Occasionally, IPTs are known to calcify, cavitate, invade the mediastinum or hilum, or present with pleural effusion. About 10% of the lesions are endobronchial. Clinically, most patients are asymptomatic, with a solitary nodule or mass detected by routine chest roentgenogram. Systemic symptoms may predominate in some, and recurrent pneumonia, collapse, pleural effusion, and a variety of mediastinal compression symptoms are not uncommon. Lab investigations may show elevated ESR, anemia, thrombocytosis, and hypergammaglobulinemia, which characteristically resolve after the lesion is excised.[5] Some of the postulated pathophysiological mechanisms include trauma or surgery, immune–autoimmune mechanism, associated with other malignancy or secondary to infection. Specific infectious agents have been incriminated, such as mycobacteria in association with spindle cell tumor, and nocardiae and mycoplasma in pulmonary pseudotumors.[5] The finding of IgG-predominant, polyclonal plasma cells and the development of about one-third of lesions after an infection further reinforces IPT being a reactive inflammatory process.

Proliferation of spindle cells, arranged in short fascicles with a focal storiform (whorled or cartwheel-like) architecture, associated with a variably dense polymorphic infiltrate of mononuclear inflammatory cells is the most consistent histopathologic finding.[9] Cytologic atypia, ganglion-like cells, P53 expression and DNA aneuploidy along with focal and/or vascular invasion and nuclear pleiomorphism are suggestive of more malignant behavior and a worse prognosis.[10]

IPTs have been shown to radiologically and clinically mimic a malignant process. Chest radiograph may show a lenticular opacity superimposed on the central portion of the lung, while CT typically shows a solitary, peripheral, sharply circumscribed mass with an anatomic bias for the lower lobes. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI; intermediate signal intensity on T1WI and high signal intensity on T2WI) may help in delineating the extent of contiguous spread.

Complete surgical resection (wedge resection preferred over lobectomy or pneumonectomy), either by video-assisted thoracoscopy or by open thoracotomy (if larger lesions and invasive nature), is the definitive treatment. If the patients are poor surgical candidates or have multiple nodules or unresectable disease, nonsurgical modalities like treatment with glucocorticoids, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy may be tried. Complete tumor excision and tumor size ≤3 cm are factors associated with a decreased risk of recurrence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the Departments of Internal Medicine, Radiology and Pulmonology/Critical Care for their perpetual support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Dehner LP. The enigmatic inflammatory pseudotumours: The current state of our understanding, or misunderstanding. J Pathol 2000;192:277-9.

- Hussain SF, Salahuddin N, Khan A, Memon SS, Fatimi SH, Ahmed R. The insidious onset of dyspnea and right lung collapse in a 35-year-old man. Chest 2005;127:1844-7.

- Singh RS, Dhaliwal RS, Puri D, Behera D, Das A. Inflammatory pseudotumour of the lung: Report of a case and review of literature. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 2001;43:231-4.

- Kim JH, Cho JH, Park MS, Chung JH, Lee JG, Kim YS, et al. Pulmonary inflammatory pseudotumor-a report of 28 cases. Korean J Intern Med 2002;17:252-8.

- Narla LD, Newman B, Spottswood SS, Narla S, Kolli R. Inflammatory pseudotumor. Radiographics 2003;23:719-29.

- Prasad MV, Thankachen R, Parihar B, Shukla V. Inflammatory pseudotumour of the lung. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2004;3:323-5.

- Bhatnagar S, Nigam S, Mandal AK. Inflammatory pseudotumour of lung. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 2001;43:55-7.

- Kishi K, Fujii T, Kohno T, Yoshimura K. Inflammatory pseudotumour affecting the lung and orbit. Respirology 2009;14:449-51.

- Hammer J, Grädel E, Signer E, Ohnacker H, Rinderknecht BP, Rutishauser M. Plasma cell granuloma of the lung: Associated laboratory findings and ultrastructural evidence of inflammatory origin. Pediatr Pulmonol 1991;10:299-303.

- Hussong JW, Brown M, Perkins SL, Dehner LP, Coffin CM. Comparison of DNA ploidy, histologic, and immunohistochemical findings with clinical outcome in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. Mod Pathol 1999;12:279-86.

| Figure 1:Chest radiograph showing a large lobulated soft tissue mass lesion overlying the left cardiac border, situated in anterior and middle mediastinum

| Figure 2:Contrast-enhanced CT thorax showing a hypodense mass lesion measuring 8.4 × 6.1 cm adjacent to left hilum without any evidence of calcification or contrast enhancement

| Figure 3:High-power view showing myofibroblasts with plump oval nuclei (thick white arrows), plasma cells (thin white arrows) and inflammatory cells, mainly lymphocytes (black arrows) in a collagenous background with myxoid areas and proliferating vessels

References

- Dehner LP. The enigmatic inflammatory pseudotumours: The current state of our understanding, or misunderstanding. J Pathol 2000;192:277-9.

- Hussain SF, Salahuddin N, Khan A, Memon SS, Fatimi SH, Ahmed R. The insidious onset of dyspnea and right lung collapse in a 35-year-old man. Chest 2005;127:1844-7.

- Singh RS, Dhaliwal RS, Puri D, Behera D, Das A. Inflammatory pseudotumour of the lung: Report of a case and review of literature. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 2001;43:231-4.

- Kim JH, Cho JH, Park MS, Chung JH, Lee JG, Kim YS, et al. Pulmonary inflammatory pseudotumor-a report of 28 cases. Korean J Intern Med 2002;17:252-8.

- Narla LD, Newman B, Spottswood SS, Narla S, Kolli R. Inflammatory pseudotumor. Radiographics 2003;23:719-29.

- Prasad MV, Thankachen R, Parihar B, Shukla V. Inflammatory pseudotumour of the lung. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2004;3:323-5.

- Bhatnagar S, Nigam S, Mandal AK. Inflammatory pseudotumour of lung. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 2001;43:55-7.

- Kishi K, Fujii T, Kohno T, Yoshimura K. Inflammatory pseudotumour affecting the lung and orbit. Respirology 2009;14:449-51.

- Hammer J, Grädel E, Signer E, Ohnacker H, Rinderknecht BP, Rutishauser M. Plasma cell granuloma of the lung: Associated laboratory findings and ultrastructural evidence of inflammatory origin. Pediatr Pulmonol 1991;10:299-303.

- Hussong JW, Brown M, Perkins SL, Dehner LP, Coffin CM. Comparison of DNA ploidy, histologic, and immunohistochemical findings with clinical outcome in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. Mod Pathol 1999;12:279-86.

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share