How I Treat Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in India

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ? Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2021; 42(06): 584-594

DOI: DOI: 10.1055/s-0041-1731979

Introduction

Survival in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) has improved from less than 10% (in the 1960s) to over 90% in developed countries.[1] These improvements were driven by optimized, risk-stratified chemotherapy and enhanced supportive care. The incorporation of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+ve) ALL has improved survival in this subset.[2] However, older age makes significant impacts on survival in ALL. Though the survival among adolescents and younger adults (AYA, 19?40 years) has improved (5-year survival: 50?70%), gains in older adults (41?60 years) with ALL have been more modest (5-year survival: 30?40%).[3] [4] Even in the best centers in the world, till recently, survival among ?elderly? ALL (>60?65 years) was poor, and only 10 to 15% were being ?cured? with?conventional?chemotherapy.[3] [5]

Adverse disease biology partly explains the drop in survival with age.[6] Older patients have higher proportions of Ph-positivity, and ?Ph-like? changes, with a lesser proportion with ?good risk? cytogenetics like the t(12;21) translocation. Better outcomes are demonstrated in AYA ALL with intensive (?pediatric-type?) chemotherapy protocols.[7] [8] However, these regimens have increased toxicity and treatment-related mortality (TRM), especially in older individuals and ?real-world? patients.[9] [10] [11] [12] India has the highest population of adolescent and young adults globally, and most centers see a significant proportion of patients in this age group.[13] [14] Indian centers report a high incidence of infectious complications (including multidrug resistant bacterial infections) during delivery of intense therapies for acute leukemias.[15] [16] Even if minimal residual disease (MRD) assessment is done, there is limited access to stem cell transplantation.[14] Thus, multiple factors contribute to poorer outcomes in adult ALL, and the challenges are country and center specific.

In this review, we use a series of representative case scenarios to discuss the management process in adult ALL. The discussions focus on presenting the standard of care while simultaneously highlighting issues specific to India. The broad principles of the decision-making process are outlined without too much detailing of the features of individual protocols.

Publication History

23 September 2021 (online)

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Introduction

Survival in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) has improved from less than 10% (in the 1960s) to over 90% in developed countries.[1] These improvements were driven by optimized, risk-stratified chemotherapy and enhanced supportive care. The incorporation of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+ve) ALL has improved survival in this subset.[2] However, older age makes significant impacts on survival in ALL. Though the survival among adolescents and younger adults (AYA, 19?40 years) has improved (5-year survival: 50?70%), gains in older adults (41?60 years) with ALL have been more modest (5-year survival: 30?40%).[3] [4] Even in the best centers in the world, till recently, survival among ?elderly? ALL (>60?65 years) was poor, and only 10 to 15% were being ?cured? with?conventional?chemotherapy.[3] [5]

Adverse disease biology partly explains the drop in survival with age.[6] Older patients have higher proportions of Ph-positivity, and ?Ph-like? changes, with a lesser proportion with ?good risk? cytogenetics like the t(12;21) translocation. Better outcomes are demonstrated in AYA ALL with intensive (?pediatric-type?) chemotherapy protocols.[7] [8] However, these regimens have increased toxicity and treatment-related mortality (TRM), especially in older individuals and ?real-world? patients.[9] [10] [11] [12] India has the highest population of adolescent and young adults globally, and most centers see a significant proportion of patients in this age group.[13] [14] Indian centers report a high incidence of infectious complications (including multidrug resistant bacterial infections) during delivery of intense therapies for acute leukemias.[15] [16] Even if minimal residual disease (MRD) assessment is done, there is limited access to stem cell transplantation.[14] Thus, multiple factors contribute to poorer outcomes in adult ALL, and the challenges are country and center specific.

In this review, we use a series of representative case scenarios to discuss the management process in adult ALL. The discussions focus on presenting the standard of care while simultaneously highlighting issues specific to India. The broad principles of the decision-making process are outlined without too much detailing of the features of individual protocols.

Case 1: Young Adult with Standard-Risk Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

A 32-year-old female, housewife, mother of two children from a poor socioeconomic background presented with weakness and recurrent fever for 2 months. Her presentation blood counts were: hemoglobin 50 g/L (5 g/dL), white blood cells (WBCs): 23.4 ? 109/L (23,400/mm3), and platelets: 34 ? 109/L (34,000/mm3). Peripheral smear showed 65% blasts. Bone marrow was completely replaced by blasts confirmed as precursor B-cell (pre-B) lymphoblastic leukemia by flow cytometry. Conventional cytogenetics showed normal karyotype, and reverse transcription polymerize chain reaction (RT-PCR) for BCR-ABL was negative. She started induction therapy with modified BFM-95 protocol.

Adult versus Pediatric protocols

Multiple trials have shown superior results using ?pediatric? type protocols in AYA patients with ALL ([Table 1]).[17] [18] [19] Patients up to the age of 50 years have been included in these studies, and the current consensus is to use pediatric protocols whenever feasible for treating young adults. At our center, we use BFM-95, a standard and frequently-used ?pediatric? regimen. Inadequate prednisolone response and adverse biology (BCR/ABL or MLL rearrangements) are considered high-risk, while, T-cell ALL (T-ALL), older ages (>6 years), and initial WBC > 10 ? 10/L constitute medium risk. We used a modified version of this protocol where most patients received the standard risk treatment with modifications done only for those who are MRD+ve.[20] Previous studies from India ([Table 2]) have reported 40 to 60% survival among AYA ALL treated with this protocol.[12] [14] Though higher TRM was noted in older Indian studies, a large multicenter study from India has shown that pediatric protocols can safely be delivered in AYA patients without excess mortality.[11] [14] Concerns about toxicities remain and, even in developed countries, a quarter of AYA patients are treated with ?adult? protocols.[21]

|

Type |

Ph type |

Center |

City |

n |

Median age in years(range) |

Treatment |

EFS% (y) |

OS% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ph-negative ALL |

1997?2003 |

PGIMER[25] |

Chandigarh |

118 |

>12 |

Modified BFM |

29 (3) |

NR |

|

1995?2009 |

CMC[79] |

Vellore |

113 |

15?60 |

Modified GMALL[a] |

51 (5) |

51(5) |

|

|

2000?2013 |

CI(14) |

Chennai |

232 |

21 (18?30) |

BFM and GMALL |

36 (5) |

39(5) |

|

|

2012?2018 |

HCC[80] |

Multiple |

572 |

21 (15?29) |

Multiple[b] |

56 (2) |

73(2) |

|

|

2013?2016 |

TMH[81] |

Mumbai |

349 |

15?25 |

BFM |

59 (3) |

61(3) |

|

|

PH-positive ALL |

2011?2016 |

RGCI[82] |

New Delhi |

63 |

35 (14?76) |

COG/UKALL[c] |

31 (4) |

46(4) |

|

2009?2012 |

TMH[83] |

Mumbai |

65 |

28 (15?53) |

MCP/BFM/other[e] |

30 (2) |

29(2) |

|

|

2012?2017 |

HCC[80] |

Multiple |

158 |

21(15?29) |

47 (2) |

67(2) |

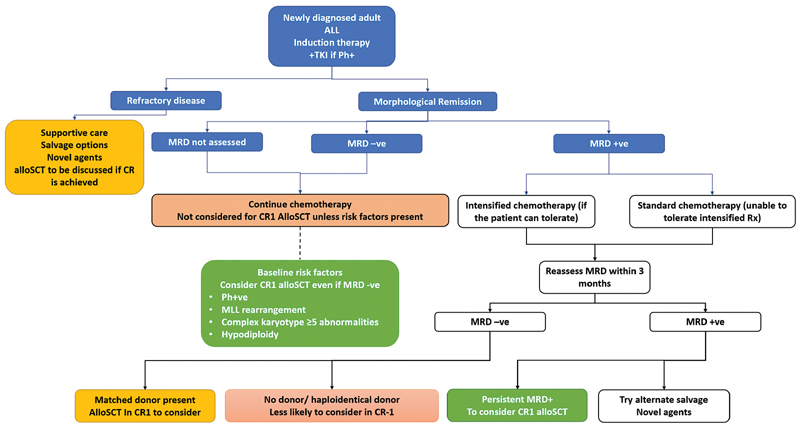

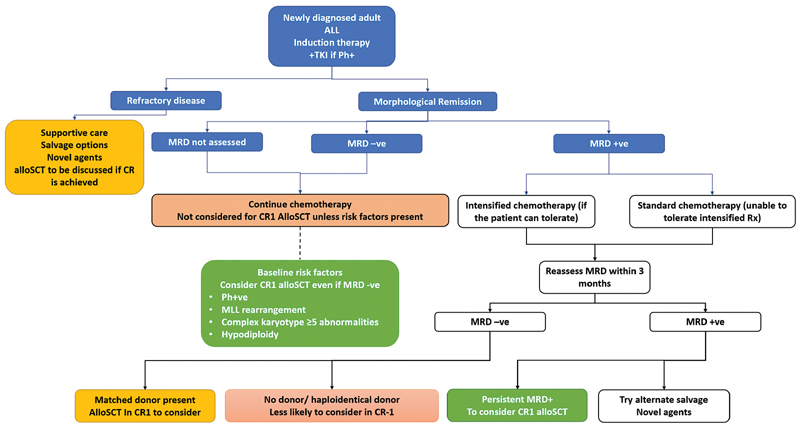

|?Fig. 1Approach to adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Decision-making process for adult ALL in India. The green boxes represent strong indications for allogeneic stem cell transplantation (alloSCT) in first complete remission (CR1), where it would be offered to all those with a sibling donor. The yellow boxes represent situations where there is benefit from alloSCT in terms of reduction of relapses. However, the procedural risk may be high (e.g., only a haploidentical donor is available or when the patient is older or has multiple comorbidities). In these situations, the decision must be individualized after clear discussions with the patient and family. Decision-making must consider the center?s experience in alternative-donor transplants. The blue box represents persistent MRD; these patients are at high risk of relapse. Their outcomes are poor with continued chemotherapy, but data also suggests that patients who are MRD+ve at the time of transplant have worse outcomes than those who undergo transplants with MRD-ve marrow. Hence, these situations also require detailed discussions. The red boxes are situations where alloSCT in CR1 is not considered (no donor, MRD-ve, and no high-risk features). MRD, minimal residual disease; Ph+ve, Philadelphia chromosome-positive;TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor. MLL, mixed lineage leukemia;

|

Factor |

Strongly consider alloSCT in CR1[a] (Green) |

Discuss the option of alloSCT in CR1[b] (Yellow) |

AlloSCT in CR1 not to be considered (Red) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Baseline risk factors |

Ph+ve disease MLL rearrangements Complex karyotype |

ETP ALL MPAL |

No baseline risk factors |

|

MRD status |

Positive postconsolidation |

Positive postinduction but negative postconsolidation |

MRD negative |

|

Age group (y) |

<40> |

45?60 |

>60?65 |

|

Donor |

Fully matched sibling or MUD |

Haploidentical donors

|?Fig. 1Approach to adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Decision-making process for adult ALL in India. The green boxes represent strong indications for allogeneic stem cell transplantation (alloSCT) in first complete remission (CR1), where it would be offered to all those with a sibling donor. The yellow boxes represent situations where there is benefit from alloSCT in terms of reduction of relapses. However, the procedural risk may be high (e.g., only a haploidentical donor is available or when the patient is older or has multiple comorbidities). In these situations, the decision must be individualized after clear discussions with the patient and family. Decision-making must consider the center?s experience in alternative-donor transplants. The blue box represents persistent MRD; these patients are at high risk of relapse. Their outcomes are poor with continued chemotherapy, but data also suggests that patients who are MRD+ve at the time of transplant have worse outcomes than those who undergo transplants with MRD-ve marrow. Hence, these situations also require detailed discussions. The red boxes are situations where alloSCT in CR1 is not considered (no donor, MRD-ve, and no high-risk features). MRD, minimal residual disease; Ph+ve, Philadelphia chromosome-positive;TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor. MLL, mixed lineage leukemia; References

|

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share