Gallbladder Cancer: Adjuvant and Palliative Treatment during Covid-19 Pandemic in India

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2020; 41(02): 132-134

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/ijmpo.ijmpo_110_20

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic does not require any formal introduction. We are going through a unique situation wherein the health-care system is at an unprecedented risk. In times of war and natural calamities such as earthquakes and floods, health-care workers continue to do their job, but the irony here is health-care workers themselves are at risk. This pandemic has created a challenge of epic proportions regarding the management of one of the most vulnerable groups of patients who have cancer. We are dealing with an overburdened health-care system, reduced availability of resources, and health-care personnel. The question that arises here is “Who bells the cat?” With this rapidly growing pandemic, it is understood that risk–benefit ratios of formerly well-established interventions will change drastically.

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is one of the most common malignancies in North India. In the Delhi Cancer Registry, it is the third-most common cancer in females. The majority of patients present in an advanced stage and the disease carries a dismal prognosis: the median survival is around 6 months, and 5-year survival was reported to be <5%.[1], [2] The limited benefit of aggressive treatments needs to be rebalanced in the scenario of the ongoing pandemic. A small study suggested that cancer patients with Covid-19 infection undergoing active treatment have a higher morbidity and mortality.[3] Further, frequent hospital visits for intravenous (IV) chemotherapy/radiotherapy are expected to overburden an already-burdened health-care system and expose patients to hospital-acquired Covid-19 infection. The members of the Science and Cost Cancer Consortium, New Delhi, have therefore formulated guidelines in these difficult times. The intent of these guidelines is to find a best middle ground for the benefit of patients, their families, their oncologists, and the health system. The guidelines are aimed to effectively use the existing infrastructure, maximally prevent the Covid-19 infection and its complications by using easily manageable chemotherapy, and reduce hospital visits as far as possible. It is emphasized that these guidelines are for use during the ongoing pandemic only. Due to the absence of specific data in a pandemic setting, the level of evidence for these recommendations is C (Expert consensus).

Publication History

Received: 28 March 2020

Accepted: 09 April 2020

Article published online:

23 May 2021

© 2020. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic does not require any formal introduction. We are going through a unique situation wherein the health-care system is at an unprecedented risk. In times of war and natural calamities such as earthquakes and floods, health-care workers continue to do their job, but the irony here is health-care workers themselves are at risk. This pandemic has created a challenge of epic proportions regarding the management of one of the most vulnerable groups of patients who have cancer. We are dealing with an overburdened health-care system, reduced availability of resources, and health-care personnel. The question that arises here is “Who bells the cat?” With this rapidly growing pandemic, it is understood that risk–benefit ratios of formerly well-established interventions will change drastically.

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is one of the most common malignancies in North India. In the Delhi Cancer Registry, it is the third-most common cancer in females. The majority of patients present in an advanced stage and the disease carries a dismal prognosis: the median survival is around 6 months, and 5-year survival was reported to be <5%.[1], [2] The limited benefit of aggressive treatments needs to be rebalanced in the scenario of the ongoing pandemic. A small study suggested that cancer patients with Covid-19 infection undergoing active treatment have a higher morbidity and mortality.[3] Further, frequent hospital visits for intravenous (IV) chemotherapy/radiotherapy are expected to overburden an already-burdened health-care system and expose patients to hospital-acquired Covid-19 infection. The members of the Science and Cost Cancer Consortium, New Delhi, have therefore formulated guidelines in these difficult times. The intent of these guidelines is to find a best middle ground for the benefit of patients, their families, their oncologists, and the health system. The guidelines are aimed to effectively use the existing infrastructure, maximally prevent the Covid-19 infection and its complications by using easily manageable chemotherapy, and reduce hospital visits as far as possible. It is emphasized that these guidelines are for use during the ongoing pandemic only. Due to the absence of specific data in a pandemic setting, the level of evidence for these recommendations is C (Expert consensus).

Palliative Setting

For patients with metastatic GBC, the median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) are dismal as shown in a recent randomized trial reported by Sharma et al. The median PFS was 4–5 months and the median OS was 8.3–9 months.[4] These experiences are comparable to findings in other studies of gemcitabine-platinum.[5], [6] These regimens require at least two hospital/day-care visits per cycle. The toxicity is not insignificant, and more than 50% of patients had Grade III or higher toxicity in both arms of the above study.[4] Most of these patients will require additional hospital or emergency room visits, and at least 10%–20% will likely need inpatient admission. These factors make these regimens unsuitable in the current pandemic scenario. Capecitabine-oxaliplatin has been noted to be slightly better in these respects, although the same concerns remain.[7]

Oral single-agent capecitabine is a relatively nontoxic treatment that requires very few hospital visits and can be taken by the patient at home in an isolated setting. In a small retrospective study (n = 8), 50% of patients with advanced GBC achieved a response; the median PFS was 6.5 months and the median OS was 9.9 months.[8] Although the dataset is very small, this activity is encouraging and comparable to that of the previously mentioned complex and more toxic regimens.

Mostly, patients with a good performance status (PS) of 0 and 1 were included in most clinical trials of metastatic GBC; the efficacy of these regimens in those with poor PS of 2–4 is not known and is likely detrimental as we have seen in other solid tumors. In the current pandemic situation, evidence-based guidelines must be practiced and best supportive care alone should be offered to patients with ECOG PS 2, 3, and 4.

Adjuvant Setting

For patients with operated GBC who require adjuvant chemotherapy, the American Society of Clinical Oncology recommends 6 months of oral capecitabine, with an option of chemoradiotherapy for patients with positive margins.[9] In the BILCAP trial, capecitabine was compared with observation and found effective only in per-protocol analysis for biliary tract cancers (78 patients had GBC).[10] Other two randomized trials of gemcitabine-oxaliplatin and gemcitabine failed to show benefit in PRODIGE-12 and BCAT trials, respectively.[11], [12] The option of chemoradiation is based on limited data, and the actual benefit over chemotherapy alone is not known. In view of the need for daily hospital visits for radiation and higher toxicity, we do not recommend chemoradiation during the ongoing pandemic.

Palliative Care and Pain Control

It is understood that the continuum of care remains intact during patients' treatment, and the patients do not feel “abandoned” due to the use of an oral regimen and less frequent hospital visits. Adequate pain relief with analgesics, management of toxicities, and care of nutritional requirements is a part of treatment. The World Health Organization ladder may be used to optimize pain control. It is suggested that majority of encounters are carried out via telemedicine as per Government of India guidelines.

Management of Covid-19 Infection during Treatment

Patients who are found to be infected with Covid-19 during treatment should have their anticancer treatment interrupted, admitted in appropriate isolation units, and treated as per the current Indian guidelines.[13]

Conclusion

The adjuvant treatment of GBC during the current pandemic should focus on switching from IV to oral chemotherapy and intensively managing patients with cancer with active Covid-19 infection. The aim is to balance the risk and benefit to the patients, their families, and health-care workers, while putting minimum possible strain on the health system.

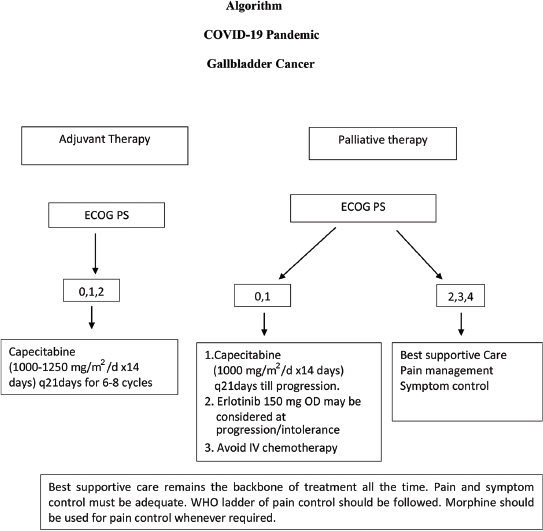

The algorithm depicted in [Figure 1] may help in decision-making for managing patients. These are recommendations only, and individual decisions as per clinical condition of the patient may be considered, in discussion with the patient according to the principles of shared decision-making.{[Figure 1]}

| Figure 1: Algorithm–Management of gallbladder cancer during COVID-19 pandemic

References

- Shukla HS, Sirohi B, Behari A, Sharma A, Majumdar J, Ganguly M. et al. Indian Council of Medical Research consensus document for the management of gall bladder cancer. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2015; 36: 79-84

- Pandey A, Raj S, Madhawi R, Devi S, Singh RK. Cancer trends in Eastern India: Retrospective hospital-based cancer registry data analysis. South Asian J Cancer 2019; 8: 215-7

- Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, Wang W, Li J, Xu K. et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: A nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol 2020; 21: 335-7

- Sharma A, Kalyan Mohanti B, Pal Chaudhary S, Sreenivas V, Kumar Sahoo R, Kumar Shukla N. et al. Modified gemcitabine and oxaliplatin or gemcitabine + cisplatin in unresectable gallbladder cancer: Results of a phase III randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer 2019; 123: 162-70

- Fiteni F, Nguyen T, Vernerey D, Paillard MJ, Kim S, Demarchi M. et al. Cisplatin/gemcitabine or oxaliplatin/gemcitabine in the treatment of advanced biliary tract cancer: A systematic review. Cancer Med 2014; 3: 1502-11

- Ramaswamy A, Ostwal V, Pinninti R, Kannan S, Bhargava P, Nashikkar C. et al. Gemcitabine-cisplatin versus gemcitabine-oxaliplatin doublet chemotherapy in advanced gallbladder cancers: A match pair analysis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2017; 24: 262-7

- Kim ST, Kang JH, Lee J, Lee HW, Oh SY, Jang JS. et al. Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin versus gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin as first-line therapy for advanced biliary tract cancers: A multicenter, open-label, randomized, phase III, noninferiority trial. Ann Oncol 2019; 30: 788-95

- Patt YZ, Hassan MM, Aguayo A, Nooka AK, Lozano RD, Curley SA. et al. Oral capecitabine for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, and gallbladder carcinoma. Cancer 2004; 101: 578-86

- Shroff RT, Kennedy EB, Bachini M, Bekaii-Saab T, Crane C, Edeline J. et al. Adjuvant Therapy for Resected Biliary Tract Cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol 2019; 37: 1015-27

- Primrose JN, Fox RP, Palmer DH, Malik HZ, Prasad R, Mirza D. et al. Capecitabine compared with observation in resected biliary tract cancer (BILCAP): A randomised, controlled, multicentre, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2019; 20: 663-73

- Edeline J, Benabdelghani M, Bertaut A, Watelet J, Hammel P, Joly JP. et al. Gemcitabine and oxaliplatin chemotherapy or surveillance in resected biliary tract cancer (PRODIGE 12-ACCORD 18-UNICANCER GI): A randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol 2019; 37: 658-67

- Ebata T, Hirano S, Konishi M, Uesaka K, Tsuchiya Y, Ohtsuka M. et al. Randomized clinical trial of adjuvant gemcitabine chemotherapy versus observation in resected bile duct cancer. Br J Surg 2018; 105: 192-202

- https://www.mohfw.gov.in/MoHFW|20 Available from: [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 02]

Address for correspondence

Publication History

Received: 28 March 2020

Accepted: 09 April 2020

Article published online:

23 May 2021

© 2020. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

References

- Shukla HS, Sirohi B, Behari A, Sharma A, Majumdar J, Ganguly M. et al. Indian Council of Medical Research consensus document for the management of gall bladder cancer. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2015; 36: 79-84

- Pandey A, Raj S, Madhawi R, Devi S, Singh RK. Cancer trends in Eastern India: Retrospective hospital-based cancer registry data analysis. South Asian J Cancer 2019; 8: 215-7

- Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, Wang W, Li J, Xu K. et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: A nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol 2020; 21: 335-7

- Sharma A, Kalyan Mohanti B, Pal Chaudhary S, Sreenivas V, Kumar Sahoo R, Kumar Shukla N. et al. Modified gemcitabine and oxaliplatin or gemcitabine + cisplatin in unresectable gallbladder cancer: Results of a phase III randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer 2019; 123: 162-70

- Fiteni F, Nguyen T, Vernerey D, Paillard MJ, Kim S, Demarchi M. et al. Cisplatin/gemcitabine or oxaliplatin/gemcitabine in the treatment of advanced biliary tract cancer: A systematic review. Cancer Med 2014; 3: 1502-11

- Ramaswamy A, Ostwal V, Pinninti R, Kannan S, Bhargava P, Nashikkar C. et al. Gemcitabine-cisplatin versus gemcitabine-oxaliplatin doublet chemotherapy in advanced gallbladder cancers: A match pair analysis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2017; 24: 262-7

- Kim ST, Kang JH, Lee J, Lee HW, Oh SY, Jang JS. et al. Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin versus gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin as first-line therapy for advanced biliary tract cancers: A multicenter, open-label, randomized, phase III, noninferiority trial. Ann Oncol 2019; 30: 788-95

- Patt YZ, Hassan MM, Aguayo A, Nooka AK, Lozano RD, Curley SA. et al. Oral capecitabine for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, and gallbladder carcinoma. Cancer 2004; 101: 578-86

- Shroff RT, Kennedy EB, Bachini M, Bekaii-Saab T, Crane C, Edeline J. et al. Adjuvant Therapy for Resected Biliary Tract Cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol 2019; 37: 1015-27

- Primrose JN, Fox RP, Palmer DH, Malik HZ, Prasad R, Mirza D. et al. Capecitabine compared with observation in resected biliary tract cancer (BILCAP): A randomised, controlled, multicentre, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2019; 20: 663-73

- Edeline J, Benabdelghani M, Bertaut A, Watelet J, Hammel P, Joly JP. et al. Gemcitabine and oxaliplatin chemotherapy or surveillance in resected biliary tract cancer (PRODIGE 12-ACCORD 18-UNICANCER GI): A randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol 2019; 37: 658-67

- Ebata T, Hirano S, Konishi M, Uesaka K, Tsuchiya Y, Ohtsuka M. et al. Randomized clinical trial of adjuvant gemcitabine chemotherapy versus observation in resected bile duct cancer. Br J Surg 2018; 105: 192-202

- https://www.mohfw.gov.in/MoHFW|20 Available from: [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 02]

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share