Ethical Dilemmas and the Moral Distress Commonly Experienced by Oncology Nurses: A Narrative Review from a Bioethics Consortium from India

CC BY 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2025; 46(02): 134-141

DOI: DOI: 10.1055/s-0044-1790583

Abstract

Nurses working in oncology frequently have to make tough moral choices, such as how to break bad news or how to make sure a dying patient receives good palliative or end-of-life care. In the context of patient care, this may limit the ethical and moral options available to nurses. This can cause moral dissonance and ethical insensitivity on the job and can be very stressful. To be able to meet ethical problems in trying times calls for capacity to recognize and know how to manage the concerns. The purpose of this article was to describe common ethical challenges and to present some methods that may be helpful when confronting them. This narrative review discusses the ethical standards that oncology nurses should uphold and implement in their daily work. Many common ethical dilemmas are also explored, and the study hopes to shed light on how novice nurses, such as students and fresh recruits, may experience when caring for cancer patients and their family caregivers. Importantly, this review also addresses aspects of how nurses can improve their skills so that they can deal with the ethical quandaries and moral discomfort that arise on a daily basis in cancer care.

Keywords

Patient Consent

Patient consent is not required due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Publication History

Article published online:

07 October 2024

© 2024. The Author(s). This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, permitting unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction so long as the original work is properly cited. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

- Dr. P. S. Chari, Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery, 1982

- Bioethics in the Pediatric ICU: Ethical Dilemmas Encountered in the Care of Critically Ill ChildrenApril N. Sharp, Journal of Pediatric Epilepsy

- Bioethics in the Pediatric ICU: Ethical Dilemmas Encountered in the Care of Critically Ill ChildrenApril N. Sharp, VCOT Open

- Bioethics in the Pediatric ICU: Ethical Dilemmas Encountered in the Care of Critically Ill ChildrenApril N. Sharp, Journal of Pediatric Epilepsy

- The Crucial Role of Psychosocial Research for Patients and Caregivers: A Narrative Review of Pediatric Psycho-Oncology Research in IndiaShraddha Namjoshi, Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology

- Dietary inflammatory index and its relation to the pathophysiological aspects of obesity: a narrative review<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- The generation and application of antioxidant peptides derived from meat protein: a review<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- Central adrenal insufficiency: who, when, and how? From the evidence to the controversies – an exploratory review<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- Guidelines from the Brazilian society of surgical oncology regarding indications and technical aspects of neck dissection in papillary, follicular, and medullar...<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- A review and other writings by Charles Dickens. Edited from the original manuscripts in the John Rylands Library<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

Abstract

Nurses working in oncology frequently have to make tough moral choices, such as how to break bad news or how to make sure a dying patient receives good palliative or end-of-life care. In the context of patient care, this may limit the ethical and moral options available to nurses. This can cause moral dissonance and ethical insensitivity on the job and can be very stressful. To be able to meet ethical problems in trying times calls for capacity to recognize and know how to manage the concerns. The purpose of this article was to describe common ethical challenges and to present some methods that may be helpful when confronting them. This narrative review discusses the ethical standards that oncology nurses should uphold and implement in their daily work. Many common ethical dilemmas are also explored, and the study hopes to shed light on how novice nurses, such as students and fresh recruits, may experience when caring for cancer patients and their family caregivers. Importantly, this review also addresses aspects of how nurses can improve their skills so that they can deal with the ethical quandaries and moral discomfort that arise on a daily basis in cancer care.

Keywords

Introduction

Nurses are important members of society because of the unique tasks they do in promoting health, preventing sickness and injury, assisting in rehabilitation, and offering support to patients in need in both hospital and community setups.[1] Nurses' primary concern is holistic health, which includes the physical, social, emotional, and spiritual requirements of their patients, and they work relentlessly to advance their patients' best interests.[1] They play a key role in ensuring everyone's well-being across the spectrum of positive health and are involved in the therapeutic decision-making process to advocate for and provide advice to the patients and their family caregivers. On a daily basis, nurses face a lot of ethical dilemmas in clinical practice, and their judgments must be guided by moral principles. Nurse, as a crucial stakeholder in health care delivery, should adhere to these principles when dealing with patients, their families or caregivers, and other health care professionals and the following principles as a set of guideline.[1]

From historical perspective, Florence Nightingale, the “Mother of Modern Nursing,” established nursing as a respectable and noble profession, and the “Nightingale Pledge,” a modified Hippocratic Oath formulated in 1893, is largely credited with establishing the code of ethics.[1] The American Nurses Association (ANA) formulated the code of ethics in the 1950s and has amended it many times.[2] In 2015, nine additional interpretative statements or clauses were added to the code of ethics to clarify nursing practice.[3] The 2015 ANA Code of Ethics includes instructive comments that might help nurses in their daily work.[2] [3] The recent version of ANA has nine provisions: the first three (1–3) address core values, the next three (4–6) on duty and loyalty, and the last three (7–9) on nursing duties outside patient interactions.[4] Most importantly, the Code covers frontline care, research, management, and public health nursing.[4] The ANA Code of Ethics for Nurses sections are addressed and briefly explained herewith:

Provision 1: The nurse practices with compassion and respect for the inherent dignity, worth, and unique attributes of every person.

The code requires nurses must know how to treat patients and families professionally while respecting their rights and coworkers' participation in care and work and emphasizing the worthiness of all individuals in the treatment paradigm.[4]

Provision 2: The nurse's primary commitment is to the patient, whether an individual, family, group, community, or population.

This implies that nurses should prioritize the patient and accept their wishes. They must report any outside or personal conflicts of interest that may impact patient care while also understanding professional constraints and outcomes.[4]

Provision 3: The nurse promotes, advocates for, and protects the rights, health, and safety of the patient.

This provision mandates that nurses must understand patient privacy and care, and prohibits nurses from treating patients while intoxicated, including with approved medicines. Nurses conducting clinical trials must understand informed consent and patient disclosure; have clear clinical and documentation skills, maintain competency standards, and report suspected medical malpractice that could damage patients. Finally, the nurse must meet institutional performance requirements, self-evaluate, undergo professional revalidation, and complete extra study when required.[4]

Provision 4: The nurse has authority, accountability, and responsibility for nursing practice; makes decisions; and takes action consistent with the obligation to provide optimal patient care.

Nursing requires thoughtful, planned, and implemented decision-making. Professional authority must handle individualism and patient ethics, and nursing responsibilities must be delegated with consideration for the work and its outcome. The nurse's accountability in those circumstances is reflected in their authoritative and responsible nursing care.[4]

Provision 5: The nurse owes the same duties to self as to others, including the responsibility to promote health and safety, preserve wholeness of character and integrity, maintain competence, and continue personal and professional growth.

The provision requires self-care as well as coworker care, and an ideal nurse will practice safe health care at home and at work. Nurses must be honest, seek for professional improvement, maintain and increase proficiency, and adapt to changes in care, trends, and innovations that contribute to personal growth.[4]

Provision 6: The nurse, through individual and collective effort, establishes, maintains, and improves the ethical environment of the work setting and conditions of employment that are conducive to safe, quality health care.

Ethical care criteria, as well as the obligation to disclose any deviations from appropriateness, should be stated out for nurses both inside and outside of their workplaces. Awareness of safety, quality, and environmental variables, as well as the proactive actions of nurses as individuals or teams, can lead to the best patient care outcomes.[4]

Provision 7: The nurse, in all roles and settings, advances the profession through research and scholarly inquiry, professional standards development, and the generation of both nursing and health policy.

According to this provision, nurses should engage in scholarly activities and research initiatives aimed to upheld practice standards and professional development. The nursing committees and boards should influence health policy and professional standards through participation and contribution. Also, professional practice guidelines should dynamically evolve as practice changes over the time.[4]

Provision 8: The nurse collaborates with other health professionals and the public to protect human rights, promote health diplomacy, and reduce health disparities.

The World Health Organization constitution (1946) states that health is a right, although health disparities persist between nations and cultures. Nurses must preserve health as a right for everyone, improve treatment through interdisciplinary teamwork, continuous nursing education, and a highly attainable standard of health. Nurses face rare situations that require diplomacy and persuasion to defend patient rights and reduce health disparities.[4]

Provision 9: The profession of nursing, collectively through its professional organization, must articulate nursing values, maintain the integrity of the profession, and integrate principles of social justice into nursing and health policy.

Bioethics is founded on two pillars: values and social justice. Nurses must continue to serve on committees and groups in order to communicate and assess values for correctness and the survival of the profession. In these groups, they must uphold social justice and should strive to retain nursing integrity, have political knowledge, collaborate with others, and contribute to global health policy.[4]

Bioethics Principles

In addition to the guiding principles of the ANA code addressing nursing ethics, Beauchamp and Childress' ethical principles serve as the cornerstone of medical ethics.[4] [5] The four main concepts of autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice serve as the foundation for all ethical interactions and behavior in nursing and across the health care sciences.[6] Nurses have a responsibility to avoid potential harm, and to consider the values and preferences of their patients, their families, and the greater community.[7] [8]

Respect for Autonomy

Patients' autonomy, which is underscored by the Nuremberg code, is essential in medical ethics because it enables mentally competent adult patients to make their own treatment decisions.[4] [5] [9] [10] [11] Nurses must ensure that patients have access to all pertinent medical information, educational resources, and treatment options.[12] [13] The nurse should refrain from swaying the patient's decision and be forthright about the therapeutic benefits, disadvantages, and treatment-induced adverse effect.[4] [11] Once the patient is aware of all essential data, nursing personnel, in collaboration with medical professionals, can develop a treatment approach that takes the patient's values and preferences into account.[4] [11] When a patient refuses medication or treatment, nurse should be compassionate and ensure that he or she has provided informed assent.[4] [11] [12] [13] If nurses are to adhere to an ethical code, they must restrict their actions to those permitted by law of the land while providing comprehensive, high-quality treatment to patients.[4] [11] The autonomy of nurses as health care professionals is also essential to their capacity to think critically and communicate effectively in all aspects of their work.[4] [12] [13]

Beneficence

Beneficence, defined as “kindness and generosity,” is a “compassionate action” motivated by a care for the well-being of others, and the ANA defines it as “conduct influenced by empathy.”[4] [5] [11] To practice beneficence, nurses must lay aside their personal emotions and provide the finest care possible for their patients, as well as take measures to improve their patients' well-being with real care and deliver what is best for them.[4] [11] This ethical notion can be observed in action when a nurse consoles a dying patient by holding their hand and administers prescriptions on time.[4] [11]

Nonmaleficence

Nonmaleficence, or “do no harm,” reflects the first principle of the Hippocratic Oath, “Primum non nocere,” and is the most commonly acknowledged principle in the field of nursing ethics.[4] [5] [11] Nurses are supposed to provide safe and effective care in all ways possible—without injuring their patients.[4] [11] Quite often, the recommended treatment is no therapy at all, and it is preferable that the benefits, dangers, and consequences of any medical attempt be thoroughly weighed and that inferior care be avoided.[4] [11] However, when a patient chooses to refuse a potentially life-saving drug, a nurse's obligation to “do no harm” as this may conflict with the latter's right to autonomy . In addition, nurses are required to report any pharmacological therapy that is causing the patient imminent physical or mental harm, such as suicidal or murderous ideas. As a result, nurses must take care not to inadvertently harm patients.[4] [11]

Justice

The concept of justice, a comprehensive ethical ideal focused on fairness, equality, and impartiality in dealing with patients and the general public is “gold standard” in health care.[4] [5] [11] In accordance with the nursing code of ethics, nurses place a high value on impartiality. Therefore, it is the responsibility of the nurse to provide care based solely on evidence, irrespective of the patient's age, race, religion, socioeconomic status, or sexual orientation.[4] [11] Regardless of their circumstances, patients have the right to be treated equally and impartially. Moreover, when individuals are treated fairly, it encourages their acceptance and active participation, which increases the likelihood of improved health outcomes.[4] [11]

Empathy

Empathy which is termed as “an individual's capacity to understand or feel what another person is experiencing from within the other person's frame of reference” is important in both nursing and health care ethics.[4] [5] [11] [14] [15] Among health care workers, the nurses have a long period of interaction with the patient and their family carers and therefore are better able to connect with them and understand how they are handling difficult situations.[16] Empathizing with patients is crucial to open up a line of communication about their concerns and preferences. An empathetic approach helps nurses to provide compassionate care and reduces patients' anxiety and distress in serious illness, pre- and postsurgical phases, or during protracted rehabilitation process.[14] Empathetic dealing is shown to enhance understanding and expression of patient's thoughts, increase the level of contentment, improve treatment adherence, and help overall improvement in the treatment paradigm.[16][17]

Veracity or Truthfulness

In nursing, honesty is an ethical requirement and the foundation of the principle of veracity and the nurse-patient relationship.[14] The Code acknowledges the responsibility of transparency as one established in concern for patients and their independence, therefore an act of “benevolent deceit,”[14] in which a professional does not tell a patient something because they believe it will harm them, is equally immoral. The nurse must always be truthful as this allows patients to express their autonomy about future care, demonstrating its relevance to the idea of autonomy. Honesty allows for the establishment of fair standards for medical care, and nurses have an ethical obligation to be frank when addressing a patient's illness, available treatments, and associated expenses.[14] Patients can utilize their autonomy (or parents/caregivers can use parental authority) to make decisions that are in their best interests if they are provided accurate information. The nurse's truthful information gives patients access to accurate and dependable information, allowing them to make informed decisions about their health care that could possibly have a long-term impact on their life.[18]

Fidelity

Fidelity termed as “faithfulness to a person, belief, or cause” and in colloquial terms as being “loyal and supportive” is vital.[14] In nursing care fidelity is an important principle and it is obligatory that the nurse adheres to her word and delivery of patient care in accordance to the high standards set by the nursing profession and keeping up with the latest evidence-based practice.[14]

Accountability

The ANA defines accountability as “being answerable to oneself and others for one's own acts” and upholds the “principles of integrity and respect for the dignity, value, and self-determination of patients” and that nurses must take responsibility for their acts and adhere to a code of ethics in order to be held accountable.[14] [19] The ANA makes it abundantly apparent that nurses, not providers, regulations, or directives, are responsible for the clinical judgments and actions associated with nursing practice.[14] It is also suggestive that accountability must include five concepts of obligation, willingness, intent, ownership, and commitment.[14] On a personal level accountability includes delivering and incorporating commitment to excel, get trained in best practices and its clinical application, take onus for errors committed and learn from constructive comments, to support other health care workers, and nurses honor commitments and being a positive role model.[14]

Professionalism

Professionalism which is defined as “an individual's adherence to a set of standards, code of conduct, or collection of qualities that characterize accepted practice within a particular area of activity” is an important aspect in health care ethics.[14] [20] [21] Nurses should be committed to their patients' rights regarding their treatment, be fair to them, and able to engage with them in a healthy unbiased and unprejudiced manner.[22] The nurse-patient relationships need to have well-defined boundaries and the best interests of the vulnerable populations need to be safeguarded, without expecting sexual, personal, or financial gain.[14] Nurses have to provide patients with accurate and comprehensive information before and after they give their consent to treatment and should make extra efforts to protect the privacy and confidentiality of the patients.[22] Nurse should teamwork with other health care providers to improve clinical proficiency, lessen the likelihood of adverse events, increase patient safety, limit wasteful spending, and improve outcomes for the patient.[22]

Nursing Ethics in Cancer Care

Cancer treatment and care is unquestionably the most challenging work in the medical sciences, and nurses who work in surgical, radiation, gynecological, pediatric, geriatric, medical, and palliative oncology units are responsible for clinical assessment, education, coordination, direct front-line therapy, symptom management, and supportive care.[23] [24] [25] Some also provide essential care, including bone marrow transplants and community-based cancer screening, diagnosis, and prevention.[23] [24] [25] In numerous nations, nurse-managed ambulatory oncology clinics provide long-term follow-up, chemotherapy screening, supportive care, fatigue treatment, and symptomatic relief. Oncology nurses with genomics training provide consultations and cancer risk assessments.[23] [24] [25]

The majority of oncology nurses regularly interact with patients who are experiencing physical and mental distress as a result of their illness, including but not limited to feelings of despondency, unhappiness, dread, loneliness, and intense and condemning feelings of human vulnerability.[26] The need to provide information about the patient's diagnosis, prognosis, risks and benefits of treatment, and disease progression prospects makes it difficult for nurses to approach these patients.[27] Clinically, the physician is responsible for informing patients about their diagnosis, treatment options, and any associated risks in order to obtain informed consent, while the nurse's duty is to provide planned care with empathy.[27]

In addition to clinical care, nursing objectives include moral responsibilities, such as preserving patients' autonomy, providing dignified physical and emotional care, and promoting the total patient welfare.[28] Despite the fact that ethical concepts and principles are the foundation of cancer nursing practice, nurses frequently face difficulties in fulfilling their professional fundamental obligations and responsibilities.[29] Unresolved conflicts can lead to feelings of frustration and helplessness, which can lead to impaired patient care, job dissatisfaction, disagreements within the health care team, exhaustion, and burnout.[29]

Stressful issues in clinical oncology include pain management and supportive care, quality of life, moral conflicts with unsuccessful treatments, resuscitation protocols, information sharing ambiguity, end-of-life care, mortality, and respect for the dying.[30] [31] Rules, principles, norms, and guidelines provide nurses with a foundation for their work, but they may not always provide the best solutions for patients because moral dilemmas frequently lack a definitive right or incorrect solution. During end-of-life care, nurses must strike a balance between patient care and encouraging family members to accept the fact and psychologically assist them during the difficult period. These are a few of the most frequent nursing concerns in an oncologic setup.

Nurses Dilemma during Breaking Bad News

Bad news, or “information that radically transforms the patient's life world,” is common in oncology.[32] The doctor/oncologist usually tells the patient and family the awful news.[33] [34] A nurse's ethical dilemmas begin with the diagnosis, as some families may exercise their right to autonomy by asking the nurse who is in regular contact with the patient to conceal about the illness, raising concerns about mental health, self-harm, or suicide.[35] [36] This is ethically challenging since the nurse must choose between maintaining their ethical beliefs and honoring a patient's confidentiality and telling the patient.[36] The nurse must assess social, religious, and cultural elements, ascertain patient's emotional condition, communicate the facts, show empathy, and encourage future planning. The nurse must also decide how much cancer information is to be shared without discouraging the patient, which can be ethically difficult during active care.[35] [36]

Nurses Dilemma during Treatment Period

Nurses must perform a full physical, cognitive, and emotional assessment, help patients set goals of care, educate patients and their families about treatment goals and side effects, and obtain informed consent for tumor board or oncologist-recommended treatment.[33] Nurses must address physical deformities, fertility loss, and sexuality issues while keeping professional boundaries within the patient's comfort zone.[35] [36] Nurses in culturally traditional societies need to be sensitive to cancer treatment surgery on the breast, vaginal region, or penis.[35] [36] In traditional orthodox cultures, nurses struggle to explain sexuality or reproduction difficulties after therapy, especially to reproductive-age patients.[35] [36] The nurse must professionally address patients' and caregivers' concerns about clinical prognosis, treatment cost, benefits and risks, and alternative therapies without intruding on attending physicians' domain.[37] [38] Handling these situation can be complicated and creates a dilemma which can be difficult to handle.

Nurses Dilemma during Change from Curative to Supportive/Palliative/Hospice Care

Localized or early-stage cancers are curable, and the treatment goal is to achieve complete remission and disease-free status.[35] [36] During treatment, doctors may decide that further treatment is futile due to the aggressiveness of the cancer, suboptimal benefits and outcomes of the chosen modalities, or tumor recurrence or metastasis based on clinical trajectories and radiological endpoints and shift to palliative care.[35] [36] At such stage, palliative care's main purpose is to limit unfavorable effects so the patient dies with less pain[35] [36] The situation becomes complex when the nurse is aware that, despite all the efforts, the patient's cancer is not responding to the treatment, and the future prospects for the condition is not favorable. For nurses who have delivered care to patients and offered comfort to their family members, it can be highly difficult when doctors discuss palliative care or treatment choices with restricted curative advantages and related expenses prior to prescribing a treatment plan.[37] Addressing these dilemmas can be difficult as nurses are expected to demonstrate both expertise and empathy without compromising patient care and institutional rules of professionalism.

Nurses Dilemma during the Course of Palliative Treatment and Care

Palliative cancer treatments mostly using radiation and/or chemotherapy improve the quality of life for patients with advanced disease by effectively managing symptoms and relieving discomfort.[38] Patients receiving palliative therapy sometimes have misconceptions about their overall prognosis, the aim of palliative treatment, and often have unrealistic hopes of their cancer being cured.[38] This affects their ability to make informed judgments, treatment options, and further complicates the situation.[38] For palliative care nurses are required to assist patients in their recovery by attending to their physical, mental, and spiritual health as well as supporting family caregivers, these situations can be particularly difficult to deal with from a moral standpoint and can cause frustration and burnout.

Nurses Dilemma during End of Life Situation

The end of life, “the last few hours or days of an individual,” is extremely distressing for patients and their family caregivers.[39] [40] [41] [42] In oncology, at this stage all curative treatment are stopped and palliative or hospice care is initiated.[43] Nurses treating end-of-life patients must control pain and uncomfortable symptoms while offering medical, emotional, social, and spiritual care to mentally cognisant patients and their families.[43] Nurses will also have to inform family members of the patient's poor prognosis and discuss death,[44] which is extremely difficult and worse especially when the patient is a child or principal support for the family.[45] [46] [47] To complicate, at times the inability to alleviate pain and approaching end-of-life care aggravate the ongoing ethical challenges for the oncology nurses and lead to moral discomfort. Professionally, obeying the treating doctor's judgment for passive euthanasia, do-not-resuscitate, and life-sustaining drug orders may increase distress.[48] [49] Nurses must communicate the patient's approaching death while satisfying family needs and safeguarding dignity, societal, and religious beliefs and this can be mentally exhausting.[48] [49]

Mitigation of Ethical Dilemma and Moral Distress in Nurses

Globally, nurses working in oncology invariably face ethical challenges and the universal belief is that eliminating them is no longer possible. Considering this, emphasis is now on training nurses to recognize them and effectively addressing these. Today, the goal is to inculcate skills to identify, build resilience, learn to cope, and prevent moral distress and burnout. The important aspect is that reports suggest that majority of ethical dilemmas included difficult situations at the end of life and are linked to putting off or avoiding tough conversations, having conflicting commitments, and not allowing others to voice their ethical opinions which consequently lead to moral distress and moral injury.[50] [51] The end result is that when disagreements over ethics arise care of critically ill patients gets more complicated and compromised. These events negatively affect patient care, which can subsequently lead to staff burnout, job departure, and will ultimately affect the hospital system. In lieu of this, across the world emphasis is now on interventions to mitigate ethical dilemma and moral distress in oncology nursing and the four R's to respond strategically to moral distress[52] and ethical deliberation[53] [54] [55] are historically found to be useful. In addition to these, a meta-analysis published by Morley et al have highlighted that interventions like “facilitated discussions, specialist consultation services; an intervention bundle; multidisciplinary rounds; self-reflection and narrative writing” are all effective in mitigate ethical dilemmas, disagreements, and the resulting moral distress.[56] Importantly, encouraging open discussion is reported to reduce the frequency and severity of disputes, emotional suffering, and moral distress.[54] [55] [56] [57]

In addition to the above said aspects it is also desired that hospital administrators can prevent and resolve ethical dilemmas by enhancing communication, creating opportunities for ongoing education to competent and trained personnel on the topic, and implement structured training to resolve ethical disputes among nurses and other health care workers through case-based vignettes.[57] More importantly, health care providers and hospital administrators should invest the necessary resources, time, and energy into improving cancer care services and should also look for ways to strengthen professional health care teams.[52] [53] [54] [55] [56] [57]

Deputation of nurses for structured short-term training in oncology and palliative care programs at cancer care and hospice centers can also be help in acquainting them with the clinical and ethical issues prevailing and on how to handle them from experienced peers. Adding training in medical ethics in oncology, palliative care, and end of life aspects in curriculum of nursing education and refresher courses for the working professionals is another important approach to help reach objective in the health care students.[54-57] It is anticipated that a concerted and sincerely planned efforts in these lines will be beneficial for the nurses and will help them identify the issues, build resilience, and assist coping with ethical dilemmas and moral distress. The outcome of these objectives will significantly help the nursing fraternity in their personal and professional endeavors, and consequentially help improve patient care and service to society.

Conclusion

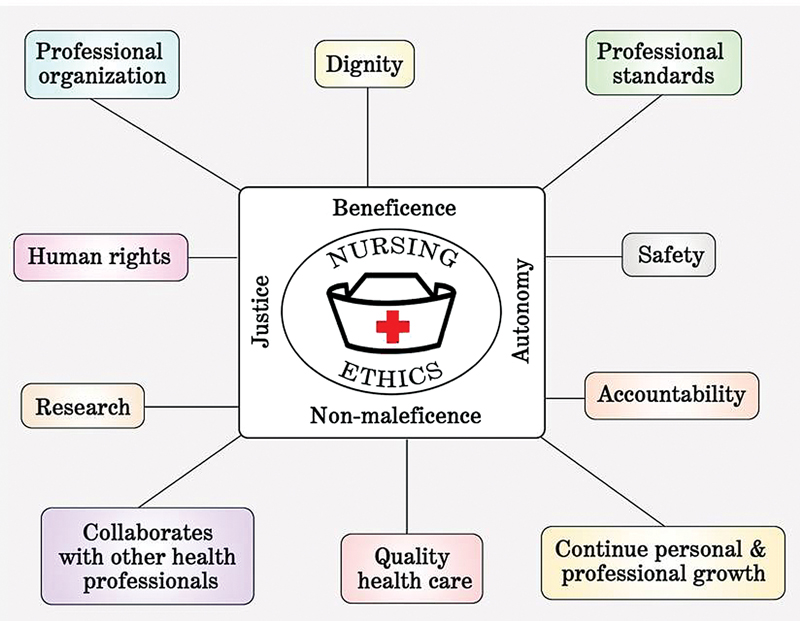

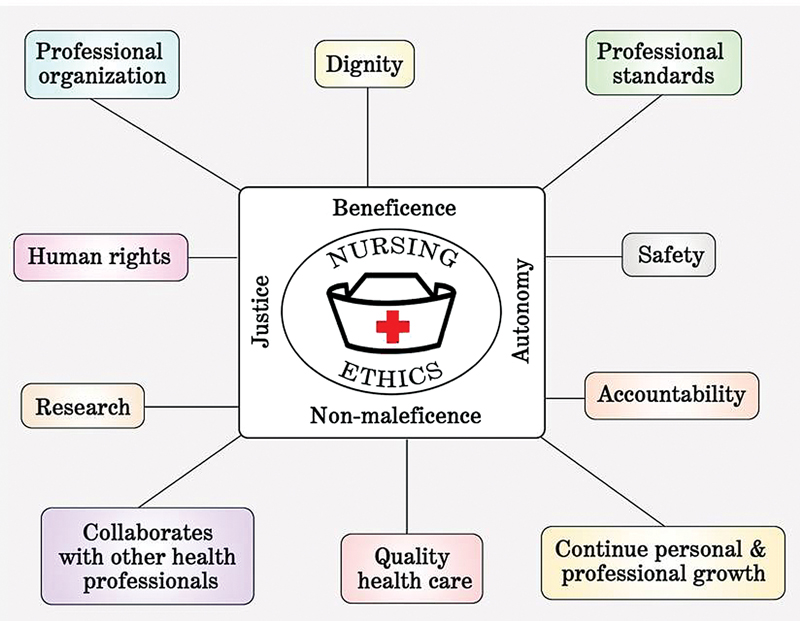

Nurses who care for cancer patients bear a heavier moral burden, and ethical difficulties abound in this field, and are vulnerable because they are constantly exposed to pain, death, and bereavement. Nurses must be taught basic ethical principles, recognize moral, cultural, religious, and spiritual concerns, and have a plan in place to address them through collaborative decision making in order to improve cancer care. The aforementioned activities should be carried out in accordance with the ethical principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence, while respecting the patient's autonomy and promoting social justice ([Fig. 1]). These concepts should be taught to nursing students and inculcated into their daily practice. As a curriculum component, bioethics education must include cancer, and nurses must have stronger basics in essential principles from the outset of their job training. Creating and maintaining a common ethical decision-making process with key stakeholders throughout the treatment process should also be included. Specific learning outcomes should be incorporated into nursing educational activities. This will help to establish a competent and morally conscious oncology workforce.

Fig. 1 Various principles and aspects important in nursing ethics.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the support and input from the Bioethics consortium and oncology colleagues for their guidance and input. The authors wish to dedicate this article to Sr Jacintha D'souza, former Principal of Father Muller College of Nursing for her support and being a mentor to Dr MS Baliga in his nursing research endeavors.

Patient Consent

Patient consent is not required due to the retrospective nature of the study.

- McBurney BH, Filoromo T. The Nightingale pledge: 100 years later. Nurs Manage 1994; 25 (02) 72-74

-

Haddad LM, Geiger RA. Nursing Ethical Considerations. [Updated August 22, 2022]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; ; 2023 January

- Epstein B, Turner M. The nursing code of ethics: its value, its history. Online J Issues Nurs 2015; 20 (02) 4

-

Faubion D. The 9 Nursing Code of Ethics (Provisions + Interpretive Statements) – Every Nurse Must Adhere To. Accessed June 1, 2022 at: https://www.nursingprocess.org/nursing-code-of-ethics-and-interpretive-statements.html

- Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 5th ed.. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001

- Stone EG. Evidence-based medicine and bioethics: implications for health care organizations, clinicians, and patients. Perm J 2018; 22: 18-30

- Christen M, Ineichen C, Tanner C. How “moral” are the principles of biomedical ethics?–a cross-domain evaluation of the common morality hypothesis. BMC Med Ethics 2014; 15: 47

- McKay R, Whitehouse H. Religion and morality. Psychol Bull 2015; 141 (02) 447-473

- Scanlon C, Fleming C. Ethical issues in caring for the patient with advanced cancer. Nurs Clin North Am 1989; 24 (04) 977-986

- Vollmann J, Winau R. Informed consent in human experimentation before the Nuremberg code. BMJ 1996; 313 (7070) 1445-1449

- Olejarczyk JP, Young M. Patient Rights and Ethics. 2022. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; ; 2023 January

- Morgan D. Respect for autonomy: is it always paramount?. Nurs Ethics 1996; 3 (02) 118-125

- van Thiel GJ, van Delden JJ. The principle of respect for autonomy in the care of nursing home residents. Nurs Ethics 2001; 8 (05) 419-431

-

American Nurses Association 2015. View the Code of Ethics for Nurses. Accessed August 2, 2023 at: https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/

- Hildebrandt M, Richardson RN, Scanlon J. Activating empathy through art in cancer communities. AMA J Ethics 2022; 24 (07) E590-E598

- Rchaidia L, Dierckx de Casterlé B, De Blaeser L, Gastmans C. Cancer patients' perceptions of the good nurse: a literature review. Nurs Ethics 2009; 16 (05) 528-542

- Adams SB. Empathy as an ethical imperative. Creat Nurs 2018; 24 (03) 166-172

- Amer AB. The ethics of veracity and it is importance in the medical ethics. Open J Nurs 2019; 9: 194-198

- Oyetunde MO, Brown VB. Professional accountability: implications for primary healthcare nursing practice. JONAS Healthc Law Ethics Regul 2012; 14 (04) 109-114

- Maarefi F, Ashk Torab T, Abaszadeh A. et al. Compliance of nursing codes of professional ethics in domain of clinical services in patients perspective. Educ Ethic Nurs 2014; 3: 27-33

- Alilu L, Parizad N, Habibzadeh H. et al. Nurses' experience regarding professional ethics in Iran: a qualitative study. J Nurs Midwifery Sci 2022; 9: 191-197

- Salloch S, Otte I, Reinacher-Schick A, Vollmann J. What does physicians' clinical expertise contribute to oncologic decision-making? A qualitative interview study. J Eval Clin Pract 2018; 24 (01) 180-186

- Levine ME. Ethical issues in cancer care: beyond dilemma. Semin Oncol Nurs 1989; 5 (02) 124-128

- McCabe MS, Coyle N. Ethical and legal issues in palliative care. Semin Oncol Nurs 2014; 30 (04) 287-295

- Rezaee N, Mardani-Hamooleh M, Ghaljeh M. Ethical challenges in cancer care: a qualitative analysis of nurses' perceptions. Res Theory Nurs Pract 2019; 33 (02) 169-182

- Vaartio H, Leino-Kilpi H, Suominen T, Puukka P. Nursing advocacy in procedural pain care. Nurs Ethics 2009; 16 (03) 340-362

- da Luz KR, Vargas MA, Schmidtt PH, Barlem EL, Tomaschewski-Barlem JG, da Rosa LM. Ethical problems experienced by oncology nurses. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2015; 23 (06) 1187-1194

- Corley MC, Minick P, Elswick RK, Jacobs M. Nurse moral distress and ethical work environment. Nurs Ethics 2005; 12 (04) 381-390

- Cohen JS, Erickson JM. Ethical dilemmas and moral distress in oncology nursing practice. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2006; 10 (06) 775-780

- Hamric AB. Empirical research on moral distress: issues, challenges, and opportunities. HEC Forum 2012; 24 (01) 39-49

- Tuca A, Viladot M, Barrera C. et al. Prevalence of ethical dilemmas in advanced cancer patients (secondary analysis of the PALCOM study). Support Care Cancer 2021; 29 (07) 3667-3675

- Narayanan V, Bista B, Koshy C. ‘BREAKS’ protocol for breaking bad news. Indian J Palliat Care 2010; 16 (02) 61-65

- Abbaszadeh A, Ehsani SR, Begjani J. et al. Nurses' perspectives on breaking bad news to patients and their families: a qualitative content analysis. J Med Ethics Hist Med 2014; 7: 18

- Warnock C, Tod A, Foster J, Soreny C. Breaking bad news in inpatient clinical settings: role of the nurse. J Adv Nurs 2010; 66 (07) 1543-1555

- Baliga MS, Rao S, Palatty PL. et al. Ethical dilemmas faced by oncologists: a qualitative study from a cancer specialty hospital in Mangalore, India. Global Bioethics Enquiry 2018; 6 (02) 106-110

- Baliga MS, Prasad K, Rao S. et al. Breaking the bad news in cancer: an in-depth analysis of varying shades of ethical issues. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2022; 43 (03) 226-232

- Benner AB. Physician and nurse relationships, a key to patient safety. J Ky Med Assoc 2007; 105 (04) 165-169

- Ghandourh WA. Palliative care in cancer: managing patients' expectations. J Med Radiat Sci 2016; 63 (04) 242-257

- Durmuş Sarıkahya S, Gelin D, Çınar Özbay S, Kanbay Y. Experiences and practices of nurses providing palliative and end-of-life care to oncology patients: a phenomenological study. Florence Nightingale J Nurs 2023; 31 (Supp1): S22-S30

- Ghaljeh M, Rezaee N, Mardani-Hamooleh M. Nurses' effort for providing end-of-life care in paediatric oncology: a phenomenological study. Int J Palliat Nurs 2023; 29 (04) 188-195

- Walker S, Zinck L, Sherry V, Shea K. A qualitative descriptive study of nurse-patient relationships near end of life. Cancer Nurs 2023; 46 (06) E394-E404

- Tanaka A, Nagata C, Goto M, Adachi K. Nurse intervention process for the thoughts and concerns of people with cancer at the end of their life: a structural equation modeling approach. Nurs Health Sci 2023; 25 (01) 150-160

- McLeod-Sordjan R. Death preparedness: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 2014; 70 (05) 1008-1019

- Laryionava K, Pfeil TA, Dietrich M, Reiter-Theil S, Hiddemann W, Winkler EC. The second patient? Family members of cancer patients and their role in end-of-life decision making. BMC Palliat Care 2018; 17 (01) 29

- Bartholdson C, Lützén K, Blomgren K, Pergert P. Experiences of ethical issues when caring for children with cancer. Cancer Nurs 2015; 38 (02) 125-132

- Alahmad G, Al-Kamli H, Alzahrani H. Ethical challenges of pediatric cancer care: interviews with nurses in Saudi Arabia. Cancer Control 2020; 27 (01) 1073274820917210

- Juárez-Villegas LE, Altamirano-Bustamante MM, Zapata-Tarrés MM. Decision-making at end-of-life for children with cancer: a systematic review and meta-bioethical analysis. Front Oncol 2021; 11: 739092

- Pettersson M, Höglund AT, Hedström M. Perspectives on the DNR decision process: a survey of nurses and physicians in hematology and oncology. PLoS One 2018; 13 (11) e0206550

- Kim H, Kim K. Palliative cancer care stress and coping among clinical nurses who experience end-of-life care. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2020; 22 (02) 115-122

- Pavlish C, Brown-Saltzman K, Jakel P, Fine A. The nature of ethical conflicts and the meaning of moral community in oncology practice. Oncol Nurs Forum 2014; 41 (02) 130-140

- Alabi RO, Hietanen P, Elmusrati M, Youssef O, Almangush A, Mäkitie AA. Mitigating burnout in an oncological unit: a scoping review. Front Public Health 2021; 9: 677915

- Buitrago J. Strategies to mitigate moral distress in oncology nursing. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2023; 27 (01) 87-91

- Steinkamp N, Gordijn B. Ethical case deliberation on the ward. A comparison of four methods. Med Health Care Philos 2003; 6 (03) 235-246

- Tan DYB, Ter Meulen BC, Molewijk A, Widdershoven G. Moral case deliberation. Pract Neurol 2018; 18 (03) 181-186

- Mehta P, Hester M, Safar AM, Thompson R. Ethics-in-oncology forums. J Cancer Educ 2007; 22 (03) 159-164

- Morley G, Field R, Horsburgh CC, Burchill C. Interventions to mitigate moral distress: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Nurs Stud 2021; 121: 103984

- Taleghani F, Shahriari M, Alimohammadi N. Empowering nurses in providing palliative care to cancer patients: action research study. Indian J Palliat Care 2018; 24 (01) 98-103

Address for correspondence

Publication History

Article published online:

07 October 2024

© 2024. The Author(s). This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, permitting unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction so long as the original work is properly cited. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

- Moral And Ethical Dilemmas In The Care Of Critically ILL PatientsDr. P. S. Chari, Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery, 1982

- Bioethics in the Pediatric ICU: Ethical Dilemmas Encountered in the Care of Critically Ill ChildrenApril N. Sharp, Journal of Pediatric Epilepsy

- Bioethics in the Pediatric ICU: Ethical Dilemmas Encountered in the Care of Critically Ill ChildrenApril N. Sharp, Journal of Pediatric Epilepsy

- Bioethics in the Pediatric ICU: Ethical Dilemmas Encountered in the Care of Critically Ill ChildrenApril N. Sharp, VCOT Open

- The Crucial Role of Psychosocial Research for Patients and Caregivers: A Narrative Review of Pediatric Psycho-Oncology Research in IndiaShraddha Namjoshi, Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology

- Development dilemmas: The methods and political ethics of growth policy, Melvin Ayogu and Don Ross (Eds.) : book review<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- Suppressive effects of exercise-conditioned serum on cancer cells: A narrative review of the influence of exercise mode, volume, and intensity<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- The ~1.4 Ga A-type granitoids in the “Chottanagpur crustal block” (India), and its relocation from Columbia to Rodinia?<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- Hydrocarbon fluid inclusions and source rock parameters: A comparison from two dry wells in the western offshore, India<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

- Paleoproterozoic emplacement and Cambrian ultrahigh-temperature metamorphism of a layered magmatic intrusion from the Central Madurai Block, southern India: Fro...<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" fill="none" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

Fig. 1 Various principles and aspects important in nursing ethics.

References

- McBurney BH, Filoromo T. The Nightingale pledge: 100 years later. Nurs Manage 1994; 25 (02) 72-74

-

Haddad LM, Geiger RA. Nursing Ethical Considerations. [Updated August 22, 2022]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; ; 2023 January

- Epstein B, Turner M. The nursing code of ethics: its value, its history. Online J Issues Nurs 2015; 20 (02) 4

-

Faubion D. The 9 Nursing Code of Ethics (Provisions + Interpretive Statements) – Every Nurse Must Adhere To. Accessed June 1, 2022 at: https://www.nursingprocess.org/nursing-code-of-ethics-and-interpretive-statements.html

- Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 5th ed.. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001

- Stone EG. Evidence-based medicine and bioethics: implications for health care organizations, clinicians, and patients. Perm J 2018; 22: 18-30

- Christen M, Ineichen C, Tanner C. How “moral” are the principles of biomedical ethics?–a cross-domain evaluation of the common morality hypothesis. BMC Med Ethics 2014; 15: 47

- McKay R, Whitehouse H. Religion and morality. Psychol Bull 2015; 141 (02) 447-473

- Scanlon C, Fleming C. Ethical issues in caring for the patient with advanced cancer. Nurs Clin North Am 1989; 24 (04) 977-986

- Vollmann J, Winau R. Informed consent in human experimentation before the Nuremberg code. BMJ 1996; 313 (7070) 1445-1449

- Olejarczyk JP, Young M. Patient Rights and Ethics. 2022. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; ; 2023 January

- Morgan D. Respect for autonomy: is it always paramount?. Nurs Ethics 1996; 3 (02) 118-125

- van Thiel GJ, van Delden JJ. The principle of respect for autonomy in the care of nursing home residents. Nurs Ethics 2001; 8 (05) 419-431

-

American Nurses Association 2015. View the Code of Ethics for Nurses. Accessed August 2, 2023 at: https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/

- Hildebrandt M, Richardson RN, Scanlon J. Activating empathy through art in cancer communities. AMA J Ethics 2022; 24 (07) E590-E598

- Rchaidia L, Dierckx de Casterlé B, De Blaeser L, Gastmans C. Cancer patients' perceptions of the good nurse: a literature review. Nurs Ethics 2009; 16 (05) 528-542

- Adams SB. Empathy as an ethical imperative. Creat Nurs 2018; 24 (03) 166-172

- Amer AB. The ethics of veracity and it is importance in the medical ethics. Open J Nurs 2019; 9: 194-198

- Oyetunde MO, Brown VB. Professional accountability: implications for primary healthcare nursing practice. JONAS Healthc Law Ethics Regul 2012; 14 (04) 109-114

- Maarefi F, Ashk Torab T, Abaszadeh A. et al. Compliance of nursing codes of professional ethics in domain of clinical services in patients perspective. Educ Ethic Nurs 2014; 3: 27-33

- Alilu L, Parizad N, Habibzadeh H. et al. Nurses' experience regarding professional ethics in Iran: a qualitative study. J Nurs Midwifery Sci 2022; 9: 191-197

- Salloch S, Otte I, Reinacher-Schick A, Vollmann J. What does physicians' clinical expertise contribute to oncologic decision-making? A qualitative interview study. J Eval Clin Pract 2018; 24 (01) 180-186

- Levine ME. Ethical issues in cancer care: beyond dilemma. Semin Oncol Nurs 1989; 5 (02) 124-128

- McCabe MS, Coyle N. Ethical and legal issues in palliative care. Semin Oncol Nurs 2014; 30 (04) 287-295

- Rezaee N, Mardani-Hamooleh M, Ghaljeh M. Ethical challenges in cancer care: a qualitative analysis of nurses' perceptions. Res Theory Nurs Pract 2019; 33 (02) 169-182

- Vaartio H, Leino-Kilpi H, Suominen T, Puukka P. Nursing advocacy in procedural pain care. Nurs Ethics 2009; 16 (03) 340-362

- da Luz KR, Vargas MA, Schmidtt PH, Barlem EL, Tomaschewski-Barlem JG, da Rosa LM. Ethical problems experienced by oncology nurses. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2015; 23 (06) 1187-1194

- Corley MC, Minick P, Elswick RK, Jacobs M. Nurse moral distress and ethical work environment. Nurs Ethics 2005; 12 (04) 381-390

- Cohen JS, Erickson JM. Ethical dilemmas and moral distress in oncology nursing practice. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2006; 10 (06) 775-780

- Hamric AB. Empirical research on moral distress: issues, challenges, and opportunities. HEC Forum 2012; 24 (01) 39-49

- Tuca A, Viladot M, Barrera C. et al. Prevalence of ethical dilemmas in advanced cancer patients (secondary analysis of the PALCOM study). Support Care Cancer 2021; 29 (07) 3667-3675

- Narayanan V, Bista B, Koshy C. ‘BREAKS’ protocol for breaking bad news. Indian J Palliat Care 2010; 16 (02) 61-65

- Abbaszadeh A, Ehsani SR, Begjani J. et al. Nurses' perspectives on breaking bad news to patients and their families: a qualitative content analysis. J Med Ethics Hist Med 2014; 7: 18

- Warnock C, Tod A, Foster J, Soreny C. Breaking bad news in inpatient clinical settings: role of the nurse. J Adv Nurs 2010; 66 (07) 1543-1555

- Baliga MS, Rao S, Palatty PL. et al. Ethical dilemmas faced by oncologists: a qualitative study from a cancer specialty hospital in Mangalore, India. Global Bioethics Enquiry 2018; 6 (02) 106-110

- Baliga MS, Prasad K, Rao S. et al. Breaking the bad news in cancer: an in-depth analysis of varying shades of ethical issues. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2022; 43 (03) 226-232

- Benner AB. Physician and nurse relationships, a key to patient safety. J Ky Med Assoc 2007; 105 (04) 165-169

- Ghandourh WA. Palliative care in cancer: managing patients' expectations. J Med Radiat Sci 2016; 63 (04) 242-257

- Durmuş Sarıkahya S, Gelin D, Çınar Özbay S, Kanbay Y. Experiences and practices of nurses providing palliative and end-of-life care to oncology patients: a phenomenological study. Florence Nightingale J Nurs 2023; 31 (Supp1): S22-S30

- Ghaljeh M, Rezaee N, Mardani-Hamooleh M. Nurses' effort for providing end-of-life care in paediatric oncology: a phenomenological study. Int J Palliat Nurs 2023; 29 (04) 188-195

- Walker S, Zinck L, Sherry V, Shea K. A qualitative descriptive study of nurse-patient relationships near end of life. Cancer Nurs 2023; 46 (06) E394-E404

- Tanaka A, Nagata C, Goto M, Adachi K. Nurse intervention process for the thoughts and concerns of people with cancer at the end of their life: a structural equation modeling approach. Nurs Health Sci 2023; 25 (01) 150-160

- McLeod-Sordjan R. Death preparedness: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 2014; 70 (05) 1008-1019

- Laryionava K, Pfeil TA, Dietrich M, Reiter-Theil S, Hiddemann W, Winkler EC. The second patient? Family members of cancer patients and their role in end-of-life decision making. BMC Palliat Care 2018; 17 (01) 29

- Bartholdson C, Lützén K, Blomgren K, Pergert P. Experiences of ethical issues when caring for children with cancer. Cancer Nurs 2015; 38 (02) 125-132

- Alahmad G, Al-Kamli H, Alzahrani H. Ethical challenges of pediatric cancer care: interviews with nurses in Saudi Arabia. Cancer Control 2020; 27 (01) 1073274820917210

- Juárez-Villegas LE, Altamirano-Bustamante MM, Zapata-Tarrés MM. Decision-making at end-of-life for children with cancer: a systematic review and meta-bioethical analysis. Front Oncol 2021; 11: 739092

- Pettersson M, Höglund AT, Hedström M. Perspectives on the DNR decision process: a survey of nurses and physicians in hematology and oncology. PLoS One 2018; 13 (11) e0206550

- Kim H, Kim K. Palliative cancer care stress and coping among clinical nurses who experience end-of-life care. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2020; 22 (02) 115-122

- Pavlish C, Brown-Saltzman K, Jakel P, Fine A. The nature of ethical conflicts and the meaning of moral community in oncology practice. Oncol Nurs Forum 2014; 41 (02) 130-140

- Alabi RO, Hietanen P, Elmusrati M, Youssef O, Almangush A, Mäkitie AA. Mitigating burnout in an oncological unit: a scoping review. Front Public Health 2021; 9: 677915

- Buitrago J. Strategies to mitigate moral distress in oncology nursing. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2023; 27 (01) 87-91

- Steinkamp N, Gordijn B. Ethical case deliberation on the ward. A comparison of four methods. Med Health Care Philos 2003; 6 (03) 235-246

- Tan DYB, Ter Meulen BC, Molewijk A, Widdershoven G. Moral case deliberation. Pract Neurol 2018; 18 (03) 181-186

- Mehta P, Hester M, Safar AM, Thompson R. Ethics-in-oncology forums. J Cancer Educ 2007; 22 (03) 159-164

- Morley G, Field R, Horsburgh CC, Burchill C. Interventions to mitigate moral distress: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Nurs Stud 2021; 121: 103984

- Taleghani F, Shahriari M, Alimohammadi N. Empowering nurses in providing palliative care to cancer patients: action research study. Indian J Palliat Care 2018; 24 (01) 98-103

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share