Chemotherapy Toxicity in Elderly Population ?65 Years: A Tertiary Care Hospital Experience from India

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2019; 40(04): 531-535

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/ijmpo.ijmpo_62_18

Abstract

Context: Trials in the elderly have established that older individuals may benefit from chemotherapy to the same extent as younger individuals. Although the elderly patient is a prototype for cancer, very few clinical trials focus on the therapeutic decisions most directly facing older adults. Aims: This study was undertaken to study the chemotherapy-induced severe toxicity among elderly. Settings and Design: This study was a prospective, observational cohort study. The study commenced in October 2014 after obtaining clearance from the hospital ethics and protocol committee. Subjects and Methods: A total of 100 patients were included in the study. All patients were of age ≥65 years, had malignancy, and were planned to start with chemotherapy. Development of Grade 3/4/5 nonhematologic (NH) or Grade 4/5 hematologic (H) toxicities was taken as the development of severe toxicity. Statistical Analysis Used: The quantitative variables were expressed as a mean ± standard deviation and compared using unpaired t-test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Results: Overall, 64 (64%) patients were able to complete their prescribed treatment. Forty-four patients (44%) of our study cohort experienced Grade 4 H or Grade 3/4 NH toxicity. The most common H Grade 4 toxicities were neutropenia (6%) and thrombocytopenia (5%). The most common NH toxicities were fatigue (18%), infection (10%), and cardiac abnormalities (4%). Conclusions: Less than 50% of elderly patients experience severe chemotherapy-related toxicity. First 30 days are most important for toxicity assessment as 45% of patients experienced toxicity in this time frame.

Publication History

Received: 17 March 2018

Accepted: 21 June 2018

Article published online:

03 June 2021

© 2020. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Context: Trials in the elderly have established that older individuals may benefit from chemotherapy to the same extent as younger individuals. Although the elderly patient is a prototype for cancer, very few clinical trials focus on the therapeutic decisions most directly facing older adults. Aims: This study was undertaken to study the chemotherapy-induced severe toxicity among elderly. Settings and Design: This study was a prospective, observational cohort study. The study commenced in October 2014 after obtaining clearance from the hospital ethics and protocol committee. Subjects and Methods: A total of 100 patients were included in the study. All patients were of age ≥65 years, had malignancy, and were planned to start with chemotherapy. Development of Grade 3/4/5 nonhematologic (NH) or Grade 4/5 hematologic (H) toxicities was taken as the development of severe toxicity. Statistical Analysis Used: The quantitative variables were expressed as a mean ± standard deviation and compared using unpaired t-test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Results: Overall, 64 (64%) patients were able to complete their prescribed treatment. Forty-four patients (44%) of our study cohort experienced Grade 4 H or Grade 3/4 NH toxicity. The most common H Grade 4 toxicities were neutropenia (6%) and thrombocytopenia (5%). The most common NH toxicities were fatigue (18%), infection (10%), and cardiac abnormalities (4%). Conclusions: Less than 50% of elderly patients experience severe chemotherapy-related toxicity. First 30 days are most important for toxicity assessment as 45% of patients experienced toxicity in this time frame.

Introduction

Aging has been defined as a loss of “entropy and fractality.”[1] Aging is not homogeneous across the elderly population and ranges from high-functioning fit adults to the elderly being bedridden. Cancer is a disease of aging, with the majority falling in the age group of above 65 years.[2] [3]

Indian perspective

Between 2010 and 2050, the share of 65 years and older is expected to increase from 5% to 14%, while the share in the oldest age group (80 and older) will triple from 1% to 3% (UN 2011).[4] The nexus of cancer and aging presents some unique issues for older cancer patients and their caregivers (familial and professional).[5] Age-related physiological changes due to both genetic (e.g., organ and systems functional reserve) and environmental influences (e.g., disease, physical and emotional stresses, lifestyle, and carcinogenic exposures) involve a progressive loss of the body’s ability to cope with stress. This may affect the growth rate of the tumor, the pharmacokinetics of drugs, and the risk of drug-related toxicity.[6]

Chemotherapy

Trials in the elderly have established that older individuals may benefit from chemotherapy to the same extent as younger individuals (as long as the chemotherapy is administered in an adequate dose intensity) but also that older individuals were more vulnerable to the complications of cytotoxic chemotherapy, especially myelotoxicity, mucositis, and cardiotoxicity.[7] [8] [9] Appropriate supportive care to manage the toxicity of chemotherapy, such as the use of growth factors, is particularly important in older patients, who are at greater risk for the toxicity associated with chemotherapy.[10]

Although the elderly patient is prototype for cancer, very few clinical trials focus on the therapeutic decisions most directly facing older adults. Historically, older adults have been underrepresented in cancer clinical trials.[11] Moreover, data are limited on the occurrence and outcomes of chemotherapy toxicity in elderly. It was with this aim of analyzing chemotherapy toxicity in the elderly cancer patients that this study was taken up.

Subjects and Methods

This study was conducted at a tertiary care hospital, Department of Medical Oncology.

This study was a prospective, observational cohort study. The study commenced in October 2014 after obtaining the clearance from the hospital ethics and protocol committee. Patients were enrolled with effect from October 2014 as per Type 1 progressive censoring scheme. Enrollment was completed in May 2016. The cutoff date for the last follow-up was September 30, 2016.

A total of 100 patients were included in the study. All patients were of age ≥65 years, had malignancy, and were planned to be started with chemotherapy only. Informed consent was obtained from all patients as per the Institute Ethics Committee. A patient information sheet was provided to all patients. All patients were subjected to a thorough history taking and physical examination, a systematic review of records, treatment received, and other clinical information.

Toxicity of the chemotherapy regimen was graded as per Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) adverse events criteria Version 4.0 Published: May 28, 2009. Development of Grade 3/4/5 nonhematologic (NH) or Grade 4/5 hematologic (H) toxicities was taken as the development of severe toxicity. Patients recruited for the study had solid-organ malignancy of various primary sites.

More than 20 types of chemotherapy regimens differing in dose and schedule were administered.

The details of the toxicity were collected and recorded. The reason for discontinuation of chemotherapy was toxicity, disease progression, or completion of planned treatment. Patients were followed throughout chemotherapy until a minimum of 1 month after the last cycle. The observations were recorded in a standard pro forma for detailed analysis and data were analyzed.

The quantitative variables were expressed as a mean ± standard deviation and compared using unpaired t-test. Further, they were grouped and expressed in terms of contingency tables wherein Chi-square test was used to assess the associations. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS Version 16.0 (IBM) software was used for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics for continuous variables and frequency distribution with their percentages were calculated wherever required.

Results

The study design included 100 elderly patients (44 females and 56 males) who satisfied the designated inclusion criteria. The mean age of the population was 68.46 ± 4.3 years. Twenty-four out of these 56 male patients experienced chemotherapy toxicity (39.2%). Among females, 22 out of 44 enrolled experienced toxicity (50%) P = 0.28.

Tumor characteristics

We enrolled oncology patients with varied primary diagnosis into our study [Table 1]. Among females, the majority of patients were those of carcinoma ovary – including primary peritoneal carcinomatosis (21 out of 44) followed by carcinoma breast (14 out of 44). Among males, the most common cancer was carcinoma lung (13 patients). Most of the patients fell in Stage 4 groups (69 out of 100).

Table 1Various tumor types enrolled in the study

|

Diagnosis |

n |

|---|---|

|

PPC – Primary peritoneal carcinoma; NHL – Non-Hodgkin lymphoma; DLBCL – Diffuse large B cell lymphoma |

|

|

Gastrointestinal |

27 |

|

Carcinoma ovary (including PPC) |

21 |

|

Breast carcinoma |

14 |

|

Carcinoma lung |

13 |

|

NHL (DLBCL) |

8 |

|

Genitourinary cancer |

8 |

|

Head-and-neck cancer |

7 |

|

Synovial sarcoma |

2 |

|

Total |

100 |

Adjuvant chemotherapy was planned in 22 patients and neoadjuvant chemotherapy in five patients. Immunochemotherapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma was given in eight patients. Sixty-five of them received palliative chemotherapy. Twenty-nine different chemotherapy regimens and schedule were used. Weekly paclitaxel and carboplatin was the most favored regime (26 out of 100 patients). The incidence of chemotherapy toxicity was maximum (75%) among the subset who had chemotherapy twice before. This group was small, consisting of only eight patients, but still it points toward the cumulative chemotherapy toxicity and vulnerability of this population toward adverse effects (P = 0.234).

More than three-fourth (77%) of the patients received prophylactic granulocyte colony stimulating factor (GCSF) support, and among them, 16.8% patients developed H toxicity. On the other side, none of the patients suffered from H toxicity with no GCSF support. It can be inferred that patients planned for more toxic chemotherapy are more likely to receive growth factor support and thus are also at more risk for H toxicity (P = 0.035). Three-fourth of the patients had ECOG PS ≤2 (76 out of 100). Twenty-four percent of patients had PS of 3. Furthermore, as anticipated, 91% of patients with PS 3 developed toxicity in comparison to 23.3% in patients with PS 1. The correlation between performance status and development of toxicity was found to be statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Two-third of the patient’s cohort had one or more comorbidity. Chemotherapy-related toxicity was 51.2%, 27.5%, and 50% in patients with none, one, or more than one comorbidity. There was no association between the presence of comorbidity and occurrence of toxicity in the study population (P = 0.107).

Chemotherapy toxicity

Chemotherapy toxicity was graded as per CTCAE version 4.0.

Overall, 64 (64%) patients were able to complete their prescribed treatment. Twelve patients stopped or changed to another chemotherapy regimen due to disease progression and 24 patients stopped the treatment due to toxicity. Two patients were lost to follow-up, and their data were censored. The overall survival was calculated as per the response of the patient as on September 30, 2016. The mean number of days of follow-up was 266.04 ± 142.38. Patients who developed chemotherapy toxicity received less chemotherapy cycles (median number of cycles 4.5) compared to patients who never had any severe chemotherapy-related toxicity (median number of cycles 6).

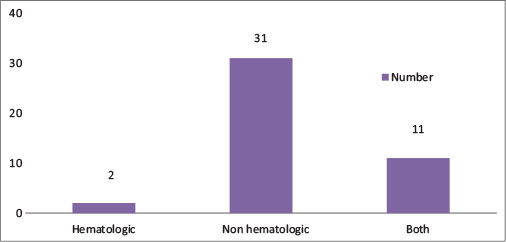

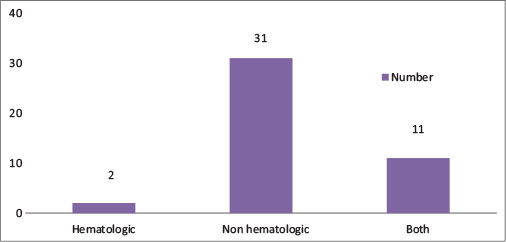

Totally 3 patients (3%) died within 1 month of starting treatment. Forty-four patients (44%) of our study cohort experienced Grade 4 H or Grade 3 or 4 NH toxicity, 13 patients (13%) had Grade 4 “H” toxicity, and 42% (42 patients) had Grade 3 or 4 “NH.” [Figure 1] shows the incidence of chemotherapy toxicity.

| Fig. 1 Chemotherapy toxicity in the study cohort

The most common H Grade 4 toxicities were neutropenia (6%) followed by thrombocytopenia (5%). The most common NH toxicity were fatigue (18%) followed by infection (10%) and cardiac abnormalities (4%) which included coronary artery disease and left ventricular dysfunction. This has been shown in [Table 2].

Table 2 Occurrence of chemotherapy-related toxicity

Among 44 patients who developed chemotherapy toxicity, the time range to suffer adverse effects of chemotherapy was 6–216 days. The median time taken to develop toxicity was 39.5 days. Therefore, one needs to be very careful during the early course of chemotherapy.

Discussion

The life expectancy in our country has doubled since independence.[12] The elderly constitutes (>65 years) 5.5%–7% of the total population of India. Eight to ten lakhs cancer patients are being diagnosed every year in India.[13] Cancer in the elderly is usually undertreated in our country due to various barriers such as financial, social, emotional, educational, and physical. It is a general assumption that the incidence and severity of side effects are greater in the elderly population. It has been proved beyond doubt that elderly also obtain benefits similar to younger patients with administration of chemotherapy.[14] This study was a prospective, observational hospital-based study in the department of medical oncology at a tertiary cancer care center which is catering to a large number of cancer patients from across the Delhi/NCR and adjoining states. This study evaluated the profile of chemotherapy toxicity in the elderly population (>65 years). The study profile included the demographic, biochemical, and clinical profile of the patients in the study.

The data for treatment in elderly are sparse due to limited representation in clinical trials.[11] Few studies have been conducted in elderly cancer population in our country. Head-and-neck cancer is the most common type of cancer in males in India (GLOBOCAN India, 2012[15]) The same is shown by Patil et al.[16] in their study from rural districts of Kerala. In our study, there were few head-and-neck cancer patients as our study was concentrating on chemotherapy only and excluded patients receiving radiation or concurrent chemoradiation. Hence, this may explain the discrepancy between our study and other similar studies. Carcinoma lung is the second most common site of cancer in India. It was also found to be the most common in the study by Goyal et al.[17] In our study also, lung cancer was the leading primary site of cancer in males.

Carcinoma cervix is one of the leading sites of cancer in females in India.[15] However, since a combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy is often employed for Ca Cervix, our study excluded such patients.

Carcinoma breast is the most common site of cancer among females in India (GLOBOCAN 2012 India)[15]. In our study also, carcinoma breast was among the top three sites of cancer in females.

Sarkar and Shahi et al.[18] reported treatment-related Grade 3 or 4 toxicity in elderly as 10.2% (4 out of 39 patients). It includes adverse effect due to surgery, radiation or chemotherapy. As per our knowledge, there is no Indian data available on the occurrence of chemotherapy toxicity in elderly. Thus, comparison of chemotherapy toxicity is done with studies all over the globe. It may be seen that the incidence of toxicity observed in different tumors may range from 27.7% (observed in Carcinoma ovary by Freyer et al.[19]) to as high as 64% (in various cancers by Extermann et al.[20]).

In both of the studies conducted by Hurria et al.,[21] [22] more than half of the patients had chemotherapy-related Grade 3–5 toxicity. In our data, the overall incidence of chemotherapy-related toxicity was lower (44%) than that observed by all the above-quoted studies. The observed difference in the incidence of toxicity between our study and the others could be, because our sample size was small, confined to only one hospital and not representative of the Indian population at large.

Hematologic toxicity was observed in 13% of patients and NH in 42% in our study. The difference in H toxicity may be explained by use of primary prophylaxis growth factors in 77% of our study patients. Our study population was younger (mean age < 70 years) than the comparative studies mentioned above leading to less incidence of toxicity (mean age >75 years).[20] [21] [22]

When scrutinized, the patients in metastatic setting have higher incidence of toxicity, that is, 49.2%. This shows the higher burden of the disease and poor performance status in these patients and affects their tolerance for treatment.

The spectrum of chemotherapy toxicity among different tumor types is affected by patient, tumor and treatment-related factors. Chemotherapy toxicity was observed in 44% of our patients compared to 63% of patients in Extermann et al.[20] group. The incidence of neutropenia, febrile neutropenia, and mucositis is similar across the studies. Among NH toxicity, fatigue not relieved on sleep and interfering with activities of daily living was the most common (16.4%). Sepsis without neutropenia was also important chemotherapy toxicity across studies. Our patient cohort represented the privileged class in India. They had better support system in terms of financial and social field.

The toxicities across the studies are variable, and it depends on amalgamation of heterogeneous patient, tumor, and chemotherapy-related factors.

Studies show that most of the patients develop toxicity during the first cycle of chemotherapy.[23] [24] Crawford et al.[23] took a heterogeneous population and observed that most (58.9%) H toxicity events occurred in the first cycle. Similarly, Lyman et al.[24] studied the timing of H toxicity in patients receiving CHOP chemotherapy in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Fifty percent of H toxicity happened in the first cycle. In our study, the range to suffer adverse effects of chemotherapy was 6–216 days. The median time taken to develop toxicity was 39.5 days. The median time to develop toxicity was 22 days in Extermann et al.[20] study. This corresponds to the period between second and third chemotherapy cycle. The period of concern is 1st month of starting chemotherapy as maximum number of events (45.4%) occurred during this timeframe. We also noted that around 50% of patients would manifest chemotherapy-related toxicity between cycles 2–3 of chemotherapy. Based on these observations, we suggest close and frequent monitoring after first and second cycle of chemotherapy to avert or to ameliorate the development of adverse effects.

Conclusions

For any elderly patient, the occurrence of chemotherapy-related toxicity is a matter of concern. In our study, it was noted that 64% of patients were able to complete the prescribed treatment with < 50% of patients experiencing severe chemotherapy-related toxicity (H and NH). The first 30 days of treatment are most important as 45% of patients experienced toxicity in this time frame. The development of chemotherapy toxicity makes an individual likely to receive less (4.5 vs. 6) number of chemotherapy cycles. We reported only Grade 3–5 toxicity; however, some Grade 2 toxicities (diarrhea, neuropathy) may also be pertinent to the geriatric population.

We suggest that large-scale, prospective studies with a greater sample size must be undertaken to describe more accurately the incidence of chemotherapy-related toxicity and that future studies also document the development of Grade 2 toxicities in elderly, which are often underrecognized.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1 Lipsitz LA. Physiological complexity, aging, and the path to frailty. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ 2004; 2004: pe16

- 2 Noone AM, Howlader N, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M. et al., (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2015, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2018. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2015/. [Last based on 2017 Nov 05]

- 3 Parry C, Kent EE, Mariotto AB, Alfano CM, Rowland JH. Cancer survivors: A booming population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2011; 20: 1996-2005

- 4 Paola S. India’s Aging Population. Population Reference Bureau; March 2012

- 5 Arokiasamy P, Bloom D, Lee J, Feeney K, Ozolins M. Longitudinal aging study in India: Vision, design, implementation, and some early results. In: Smith JP, Majmundar M. editors Aging in Asia: Findings From New and Emerging Data Initiatives. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2012

- 6 Carreca I, Balducci L, Extermann M. Cancer in the older person. Cancer Treat Rev 2005; 31: 380-402

- 7 Zinzani PL, Storti S, Zaccaria A, Moretti L, Magagnoli M, Pavone E. et al. Elderly aggressive-histology non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma:First-line VNCOP-B regimen experience on 350 patients. Blood 1999; 94: 33-8

- 8 Gómez H, Mas L, Casanova L, Pen DL, Santillana S, Valdivia S. et al. Elderly patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated with CHOP chemotherapy plus granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor: Identification of two age subgroups with differing hematologic toxicity. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 2352-8

- 9 Sonneveld P, de Ridder M, van der Lelie H, Nieuwenhuis K, Schouten H, Mulder A. et al. Comparison of doxorubicin and mitoxantrone in the treatment of elderly patients with advanced diffuse non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma using CHOP versus CNOP chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 1995; 13: 2530-9

- 10 O’Reilly SE, Connors JM, Howdle S, Hoskins P, Klasa R, Klimo P. et al. In search of an optimal regimen for elderly patients with advanced-stage diffuse large-cell lymphoma: Results of a phase II study of P/DOCE chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 1993; 11: 2250-7

- 11 Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, Coltman Jr. CA, Albain KS. Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 2061-7

- 12 Parikh PM, Bakshi AV. Cancer in the elderly – Get ready for the ’epidemic’. In: Gupta SB. editor API Medicine Update. Vol. 15. Association of Physicians of India. Mumbai: Printed by Jaypee brothers medical Publishers (P) Ltd; 2005

- 13 Agarwal SP, Rao YN, Gupta S. National Cancer control Program (NCCP). Fifty Years of Cancer Control in India. 1st ed. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. GOI; 2002

- 14 Sargent DJ, Goldberg RM, Jacobson SD, Macdonald JS, Labianca R, Haller DG. et al. A pooled analysis of adjuvant chemotherapy for resected colon cancer in elderly patients. N Engl J Med 2001; 345: 1091-7

- 15 Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M. et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v 1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC Cancer Base No. 11. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. Available from: http://www.globocan.iarc.fr. [Last accessed on 2016 Dec 26]

- 16 Patil VM, Chakraborty S, Dessai S, Kumar SS, Ratheesan K, Bindu T. et al. Patterns of care in geriatric cancer patients - an audit from a rural based hospital cancer registry in Kerala. Indian J Cancer 2015; 52: 157-61

- 17 Goyal LK, Jasuja SK, Meena H, Hooda L, Hasan SI, Agrawal D. Cancer in Geriatric patients: A single center observational study. Sch J App Med Sci 2016; 4: 1781-5

- 18 Sarkar A, Shahi U. Assessment of cancer care in Indian elderly cancer patients: A single center study. South Asian J Cancer 2013; 2: 202-8

- 19 Freyer G, Geay JF, Touzet S, Provencal J, Weber B, Jacquin JP. et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment predicts tolerance to chemotherapy and survival in elderly patients with advanced ovarian carcinoma: A GINECO study. Ann Oncol 2005; 16: 1795-800

- 20 Extermann M, Boler I, Reich RR, Lyman GH, Brown RH, DeFelice J. et al. Predicting the risk of chemotherapy toxicity in older patients: The chemotherapy risk assessment scale for high-age patients (CRASH) score. Cancer 2012; 118: 3377-86

- 21 Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, Owusu C, Klepin HD, Gross CP. et al. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: A prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 3457-65

- 22 Hurria A, Mohile S, Gajra A, Klepin H, Muss H, Chapman A. et al. Validation of a prediction tool for chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 2366-71

- 23 Crawford J, Dale DC, Kuderer NM, Culakova E, Poniewierski MS, Wolff D. et al. Risk and timing of neutropenic events in adult cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: The results of a prospective nationwide study of oncology practice. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2008; 6: 109-18

- 24 Lyman GH, Morrison VA, Dale DC, Crawford J, Delgado DJ, Fridman M. et al. Risk of febrile neutropenia among patients with intermediate-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma receiving CHOP chemotherapy. Leuk Lymphoma 2003; 44: 2069-76

Address for correspondence

Dr. Aditi MittalFlat No. 301, 3rd Floor, Sangam Residency, Vijay Nagar, Opposite Kartarpura Phatak, Jaipur ‑ 302 006, RajasthanIndiaEmail: aditi120985@gmail.comPublication History

Received: 17 March 2018

Accepted: 21 June 2018

Article published online:

03 June 2021© 2020. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

| Fig. 1 Chemotherapy toxicity in the study cohort

References

- 1 Lipsitz LA. Physiological complexity, aging, and the path to frailty. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ 2004; 2004: pe16

- 2 Noone AM, Howlader N, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M. et al., (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2015, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2018. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2015/. [Last based on 2017 Nov 05]

- 3 Parry C, Kent EE, Mariotto AB, Alfano CM, Rowland JH. Cancer survivors: A booming population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2011; 20: 1996-2005

- 4 Paola S. India’s Aging Population. Population Reference Bureau; March 2012

- 5 Arokiasamy P, Bloom D, Lee J, Feeney K, Ozolins M. Longitudinal aging study in India: Vision, design, implementation, and some early results. In: Smith JP, Majmundar M. editors Aging in Asia: Findings From New and Emerging Data Initiatives. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2012

- 6 Carreca I, Balducci L, Extermann M. Cancer in the older person. Cancer Treat Rev 2005; 31: 380-402

- 7 Zinzani PL, Storti S, Zaccaria A, Moretti L, Magagnoli M, Pavone E. et al. Elderly aggressive-histology non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma:First-line VNCOP-B regimen experience on 350 patients. Blood 1999; 94: 33-8

- 8 Gómez H, Mas L, Casanova L, Pen DL, Santillana S, Valdivia S. et al. Elderly patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated with CHOP chemotherapy plus granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor: Identification of two age subgroups with differing hematologic toxicity. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 2352-8

- 9 Sonneveld P, de Ridder M, van der Lelie H, Nieuwenhuis K, Schouten H, Mulder A. et al. Comparison of doxorubicin and mitoxantrone in the treatment of elderly patients with advanced diffuse non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma using CHOP versus CNOP chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 1995; 13: 2530-9

- 10 O’Reilly SE, Connors JM, Howdle S, Hoskins P, Klasa R, Klimo P. et al. In search of an optimal regimen for elderly patients with advanced-stage diffuse large-cell lymphoma: Results of a phase II study of P/DOCE chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 1993; 11: 2250-7

- 11 Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, Coltman Jr. CA, Albain KS. Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 2061-7

- 12 Parikh PM, Bakshi AV. Cancer in the elderly – Get ready for the ’epidemic’. In: Gupta SB. editor API Medicine Update. Vol. 15. Association of Physicians of India. Mumbai: Printed by Jaypee brothers medical Publishers (P) Ltd; 2005

- 13 Agarwal SP, Rao YN, Gupta S. National Cancer control Program (NCCP). Fifty Years of Cancer Control in India. 1st ed. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. GOI; 2002

- 14 Sargent DJ, Goldberg RM, Jacobson SD, Macdonald JS, Labianca R, Haller DG. et al. A pooled analysis of adjuvant chemotherapy for resected colon cancer in elderly patients. N Engl J Med 2001; 345: 1091-7

- 15 Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M. et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v 1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC Cancer Base No. 11. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. Available from: http://www.globocan.iarc.fr. [Last accessed on 2016 Dec 26]

- 16 Patil VM, Chakraborty S, Dessai S, Kumar SS, Ratheesan K, Bindu T. et al. Patterns of care in geriatric cancer patients - an audit from a rural based hospital cancer registry in Kerala. Indian J Cancer 2015; 52: 157-61

- 17 Goyal LK, Jasuja SK, Meena H, Hooda L, Hasan SI, Agrawal D. Cancer in Geriatric patients: A single center observational study. Sch J App Med Sci 2016; 4: 1781-5

- 18 Sarkar A, Shahi U. Assessment of cancer care in Indian elderly cancer patients: A single center study. South Asian J Cancer 2013; 2: 202-8

- 19 Freyer G, Geay JF, Touzet S, Provencal J, Weber B, Jacquin JP. et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment predicts tolerance to chemotherapy and survival in elderly patients with advanced ovarian carcinoma: A GINECO study. Ann Oncol 2005; 16: 1795-800

- 20 Extermann M, Boler I, Reich RR, Lyman GH, Brown RH, DeFelice J. et al. Predicting the risk of chemotherapy toxicity in older patients: The chemotherapy risk assessment scale for high-age patients (CRASH) score. Cancer 2012; 118: 3377-86

- 21 Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, Owusu C, Klepin HD, Gross CP. et al. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: A prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 3457-65

- 22 Hurria A, Mohile S, Gajra A, Klepin H, Muss H, Chapman A. et al. Validation of a prediction tool for chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 2366-71

- 23 Crawford J, Dale DC, Kuderer NM, Culakova E, Poniewierski MS, Wolff D. et al. Risk and timing of neutropenic events in adult cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: The results of a prospective nationwide study of oncology practice. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2008; 6: 109-18

- 24 Lyman GH, Morrison VA, Dale DC, Crawford J, Delgado DJ, Fridman M. et al. Risk of febrile neutropenia among patients with intermediate-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma receiving CHOP chemotherapy. Leuk Lymphoma 2003; 44: 2069-76

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share