Candida albicans endocarditis in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A dreaded complication of intensive chemotherapy

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2013; 34(01): 28-30

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/0971-5851.113414

Abstract

Candida endocarditis is a rare entity during febrile neutropenia due to early introduction of empirical antifungal therapy. Early surgical intervention has diagnostic and therapeutic importance in Candida endocarditis. We report a case of Candida albicans endocarditis in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia on chemotherapy. The role of surgical intervention is discussed.

Publication History

Article published online:

20 July 2021

© 2013. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Candida endocarditis is a rare entity during febrile neutropenia due to early introduction of empirical antifungal therapy. Early surgical intervention has diagnostic and therapeutic importance in Candida endocarditis. We report a case of Candida albicans endocarditis in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia on chemotherapy. The role of surgical intervention is discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Aggressive treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in children with intensive chemotherapy has improved survival rates significantly, although it often leads to increased infectious complications. Prolonged neutropenia and steroid use are the predominant risk factors associated with fungal infections in these patients. Although Candida endocarditis is a rare entity during febrile neutropenia due to the early introduction of empirical antifungal therapy, it is difficult to treat and may lead to considerable morbidity and high mortality. We report here a case of Candida albicans endocarditis in a child with ALL on chemotherapy.

CASE REPORT

A 7-year-old boy presented with slowly progressive generalized lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly. Peripheral blood and bone marrow examination revealed diagnosis of t-cell ALL. Central nervous system was uninvolved. Chemotherapy was initiated as per MCP 841 protocol. He achieved remission after induction and received two cycles of high-dose cytarabine (I2A) and repeat induction (RI1). Following high-dose cytarabine, he developed febrile neutropenia and necrotizing cellulitis at left wrist requiring higher antibiotics. After the second dose of high-dose cytarabine, he had central venous catheter (CVC)-related blood stream infection with Candida parapsilosis. The organism was isolated both from the catheter (peripherally inserted central catheter) and peripheral blood. The organism was sensitive to fluconazole, amphotericin-B, and voriconazole in vitro, but he did not respond clinically or microbiologically to intravenous fluconazole given for 10 days. Hence, the catheter was removed.

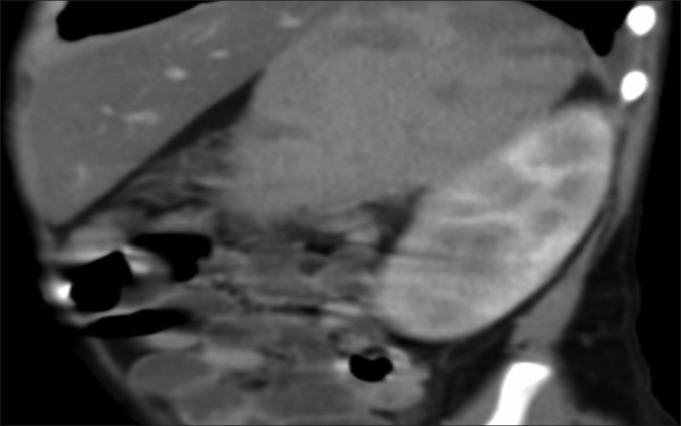

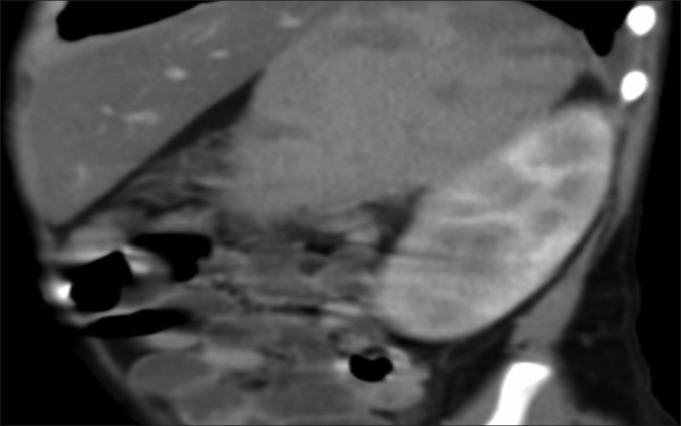

At the end of repeat induction, he developed non-neutropenic fever. In view of impending neutropenia, he was started on piperacillin–tazobactum and amikacin. C-reactive protein was elevated on day 1 (76.5 mg/L). He became severely neutropenic by the fifth day of fever. As fever spikes continued, antibiotics were changed to meropenem and vancomycin. Multiple blood cultures did not detect any organisms. In absence of defervescence, liposomal amphotericin-B was added after 7 days of antibiotics. As fever still persisted, antibiotics were changed to ceftazidime and tiecoplanin. Abdominal ultrasound revealed hepatosplenomegaly with splenic infarcts and internal echoes in urinary bladder. Computed tomography revealed multiple wedge-shaped hypodense areas in spleen and both kidneys suggestive of infarcts [Figure 1]. Urine analysis was normal and urine culture was sterile. The fever persisted after resolution of neutropenia. A 2D echocardiogram revealed multiple vegetations (largest 1.4 × 0.7 cm) on the septal and anterior leaflets of the tricuspid valve (TV). All cultures were negative. In view of blood culture-negative infective endocarditis (BCNIE), vancomycin and gentamycin were started and liposomal amphotericin-B was continued.

| Fig. 1 Computed tomography scan abdomen showing splenic and renal infarcts

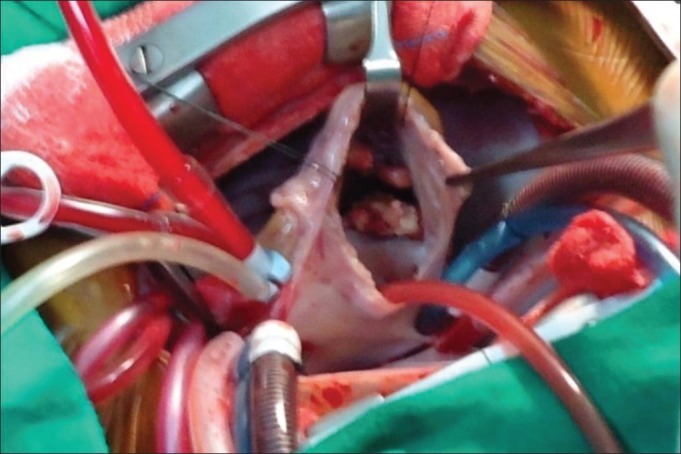

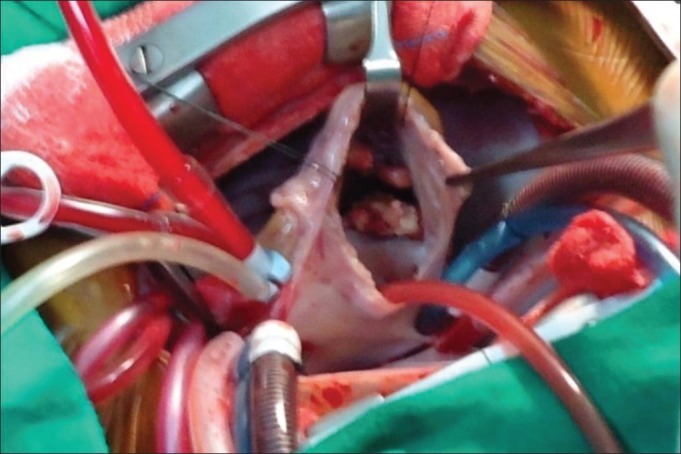

In view of persistent fever spikes and the absence of reduction of vegetations after 13 days of vancomycin and gentamycin and 19 days of amphotericin-B, option of surgery was considered. Multiple vegetations were noticed intra-operatively on all three leaflets of TV, largest (2.5 × 2.0 × 2.5 cm) being on the septal leaflet and one each on anterior and lateral leaflet [Figure 2]. Surgical excision of the vegetations was done from anterior and lateral leaflets. The septal leaflet was excised due to large adherent vegetation. Postoperatively, he developed acute renal failure, metabolic acidosis, and refractory septic shock and succumbed on the third postoperative day. The culture from the vegetations grew C. albicans.

| Fig. 2 Large vegetations on tricuspid valve noted during surgery

DISCUSSION

Infective endocarditis (IE) usually involves the left-sided valves, and involvement of right-sided valves is found only in 5-10% cases being common in intravenous drug users.[1] The presence of a CVC is a common risk factor for tricuspid valve endocarditis. Mechanical disruption of the endothelium caused by the CVC may result in non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis, which then facilitates adherence of microorganisms and infection. The most common organism associated with CVC-associated endocarditis is coagulase-negative staphylococci.[2] Candida endocarditis is a rare entity. Our patient had right-sided endocarditis following CVC infection with Candidia.

Blood culture-negative infective endocarditis (BCNIE) occurring in 2.5-31% of cases is usually due to fastidious bacteria and fungi or due to prior antibiotic administration. These organisms may be particularly common in IE affecting patients with prosthetic valves, indwelling venous lines, pacemakers, renal failure, and immunocompromised states.[2] Although polymerase chain reaction allows rapid and reliable detection of fastidious and non-culturable agents in patients with IE, pathological examination and culture of resected valvular tissue or embolic fragments remain the gold standard for the diagnosis of IE.[2,3]

Polymicrobial Candida endocarditis has been reported in literature. In our patient, two different species of Candida were isolated—Candida parapsilosis from CVC and Candida albicans from the vegetations. It is possible that the CVC was colonized with both Candida species without isolation of C. albicans from blood culture.

For treating Candida native valve endocarditis, combined medical and surgical therapy is currently recommended by Infectious Disease Society of America.[4] Liposomal amphotericin-B with or without flucytosine is the current drug recommendation along with valve replacement followed by at least 6 weeks of antifungal therapy following surgery. Caspofungin has been recommended as alternative treatment. A systematic review of the published literature revealed significantly less mortality with adjunctive surgery or combination antifungal therapy than monotherapy.[5] Anecdotal reports mention good outcomes with caspofungin without the need for surgery.[6,7,8]

We continued empiric amphotericin-B in our patient as the C. parapsilosis from CVC was sensitive to this drug and the C. albicans etiology was only established postmortem.

Operative mortality in infective endocarditis lies between 5 and 15%. Immediate postoperative complications are coagulopathy, acute renal failure, stroke, low cardiac output syndrome, and pneumonia.[9] The cause of death is often multifactorial, with a combination of these. Vegetation length >20 mm and fungal etiology were the main predictors of death in a recent large retrospective cohort of right-sided infective endocarditis in intravenous drug users.[10]

CONCLUSION

Candida endocarditis, though rare, is emerging as an important infectious disease. High index of suspicion in presence of immunodeficiency can lead to early diagnosis. Early surgical intervention has diagnostic and therapeutic importance. With the advent of newer and more effective antifungal agents such as the echinocandins the prompt initiation of treatment may help decrease the morbidity and mortality of this dreaded condition.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Cardiothoracic Surgeon Dr. Shirish Borker who performed the surgery and provided the intraoperative photograph for this publication.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

| Fig. 1 Computed tomography scan abdomen showing splenic and renal infarcts

| Fig. 2 Large vegetations on tricuspid valve noted during surgery

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share