Bacteriological profile and antibiotic susceptibility patterns of clinical isolates in a tertiary care cancer center

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2016; 37(01): 20-24

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/0971-5851.177010

Abstract

Introduction: This increased risk of bacterial infections in the cancer patient is further compounded by the rising trends of antibiotic resistance in commonly implicated organisms. In the Indian setting this is particularly true in case of Gram negative bacilli such as Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter spp. Increasing resistance among Gram positive organisms is also a matter of concern. The aim of this study was to document the common organisms isolated from bacterial infections in cancer patients and describe their antibiotic susceptibilities. Methods: We conducted a 6 month study of all isolates from blood, urine, skin/soft tissue and respiratory samples of patients received from medical and surgical oncology units in our hospital. All samples were processed as per standard microbiology laboratory operating procedures. Isolates were identified to species level and susceptibility tests were performed as per Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines -2012. Results: A total of 285 specimens from medical oncology (114) and surgical oncology services (171) were cultured. Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and Acinetobacter spp. were most commonly encountered. More than half of the Acinetobacter strains were resistant to carbapenems. Resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae to cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones and carbapenems was >50%. Of the Staphylococcus aureus isolates 41.67% were methicillin resistant. Conclusion: There is, in general, a high level of antibiotic resistance among gram negative bacilli, particularly E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter spp. Resistance among Gram positives is not as acute, although the MRSA incidence is increasing.

Publication History

Article published online:

12 July 2021

© 2016. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Introduction:

This increased risk of bacterial infections in the cancer patient is further compounded by the rising trends of antibiotic resistance in commonly implicated organisms. In the Indian setting this is particularly true in case of Gram negative bacilli such as Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter spp. Increasing resistance among Gram positive organisms is also a matter of concern. The aim of this study was to document the common organisms isolated from bacterial infections in cancer patients and describe their antibiotic susceptibilities.

Methods:

We conducted a 6 month study of all isolates from blood, urine, skin/soft tissue and respiratory samples of patients received from medical and surgical oncology units in our hospital. All samples were processed as per standard microbiology laboratory operating procedures. Isolates were identified to species level and susceptibility tests were performed as per Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines -2012.

Results:

A total of 285 specimens from medical oncology (114) and surgical oncology services (171) were cultured. Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and Acinetobacter spp. were most commonly encountered. More than half of the Acinetobacter strains were resistant to carbapenems. Resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae to cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones and carbapenems was >50%. Of the Staphylococcus aureus isolates 41.67% were methicillin resistant.

Conclusion:

There is, in general, a high level of antibiotic resistance among gram negative bacilli, particularly E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter spp. Resistance among Gram positives is not as acute, although the MRSA incidence is increasing.

INTRODUCTION

In spite of the vast advances made by medical science in cancer treatment, infections remain a major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients diagnosed with cancer. The cancer patient is immunocompromised because of the nature of the disease itself and also due to interventions in the form of chemotherapy etc., in addition, there are usually other associated risk factors for acquiring infection such as long term catheterization, mucositis due to cytotoxic agents, neutropenia, and stem cell transplantation.[1]

This increased risk of bacterial infections is further compounded by the rising trends of antibiotic resistance in commonly implicated organisms all over the world. This is particularly true in the case of members of Enterobacteriaceae group like Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae and the nonfermenter group of organisms such as Acinetobacter spp. in the Indian setting. There is already widespread resistance to the cephalosporins as shown by ESBL (extended spectrum β-lactamase) and Amp C producers among the Enterobacteriaceae.[2] Rampant use of antibiotics has unfortunately led to increasing resistance to the carbapenems as well, and this is generally due to carbapenemase production by the organisms.[3] Prevalence of Metallo-beta-lactamase (MBL) producing organisms including New Delhi MBL-1 (NDM-1) is also on the rise in India.[4]

Increasing resistance among Gram-positive organisms is also a matter of concern. High rates of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in clinical samples have been noted in one study from North East India.[5] Similarly, resistance to the glycopeptide antibiotics such as vancomycin and tiecoplanin among clinical isolates of enterococci is also increasing.[6] Empirical treatment of infection in the cancer patient is often arbitrarily attempted by administration of broad spectrum or combination antibiotics until culture, and susceptibility results are available. This could be made more evidence-based if the clinician has adequate information on the spectrum of microorganisms and the antimicrobial susceptibility patterns prevalent in that particular setting. It is possible that these patterns may differ from one geographical region to another and even from one hospital to another. The aim of this study is to document the common organisms isolated in cancer patients and describe their antibiotic susceptibilities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a 6 month study of all isolates from samples of patients received from medical and surgical oncology units from July 2013 to December 2013. Medical oncology included all hematolymphoid malignancies and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Surgical oncology included all other patients with solid tumors. All relevant samples were collected as per hospital sample collection protocol from various clinical areas; these included blood, pus/wound swabs, sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage, urine, etc., all samples were processed as per standard microbiology laboratory operating procedures.[7] Isolates were generally identified up to species level by means of various biochemical tests. Susceptibility tests were performed as per Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, USA) guidelines 2012.[8] Disc diffusion technique was the default method used for antibiotic susceptibility testing. In brief, lawn cultures of appropriate inoculum of respective organisms were performed in Mueller Hinton Agar (or Mueller-Hinton Blood agar for fastidious organisms) and antibiotic discs of required strengths were placed on the surface of the inoculated media and these were then incubated overnight. Zones of inhibition were measured the next day and were correlated with CLSI interpretive breakpoints to characterize them as Sensitive, Intermediate, and Resistant. For drugs such as colistin for which CLSI breakpoints are not available, the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing interpretive breakpoints were used. In the case of other drugs like cefoperazone-sulbactam, cefepime-tazobactam, etc., interpretive breakpoints were provided by the manufacturer. S. aureus ATCC 25923, E. coli ATCC 25922 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 were used for Quality control.

For Gram-positive organisms, the antibiotics to be tested and reported were chosen from the following (depending on the organism isolated): Penicillin (10 units), erythromycin (15 μg), clindamycin (2 μg), amoxicillin-clavulanate (20/10 μg), ampicillin (10 μg), cefoxitin (30 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), vancomycin (30 μg/MIC), teicoplanin (30 μg), linezolid (30 μg), and co-trimoxazole (1.25/23.75 μg).

For Gram-negative, the antibiotics for respective organisms were chosen from the following: Amoxicillin-clavulanate (20/10 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), levofloxacin (5 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), amikacin (30 μg), netilmycin (30 μg), cefuroxime (30 μg), cefoltaxime (30 μg), ceftazidime (30 μg), cefepime (30 μg), cefoperazone-sulbactam (75/25 μg), cefepime-tazobactam (30/10 μg), imipenem (10 μg), and meropenem (10 μg). Colistin susceptibility was performed by MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) method, with E-test strips.

RESULTS

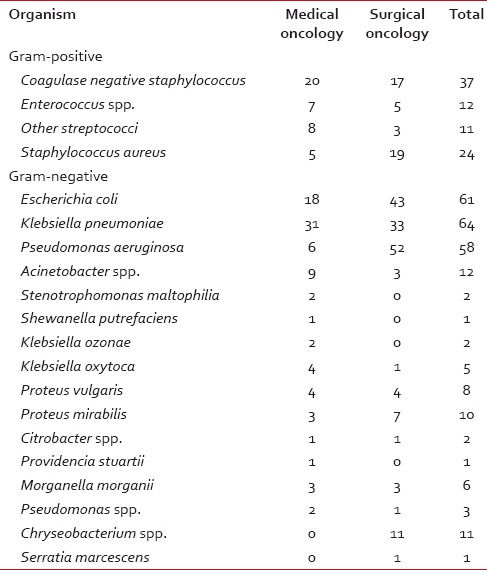

A total of 285 specimens from medical oncology (114) and surgical oncology services (171) were cultured. Table 1 shows the numbers of various specimens received from medical and surgical oncology services. Table 2 profiles the organisms isolated from all patients. ESBL producers among E. coli and K. pneumoniae were 38.46 and 35.17%, respectively.

Table 1

Breakup of specimens received for bacterial culture and sensitivity

Table 2

Organism profiles for medical and surgical oncology

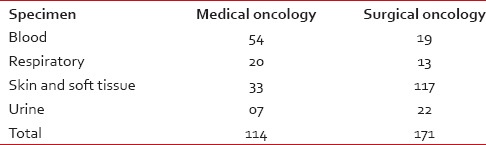

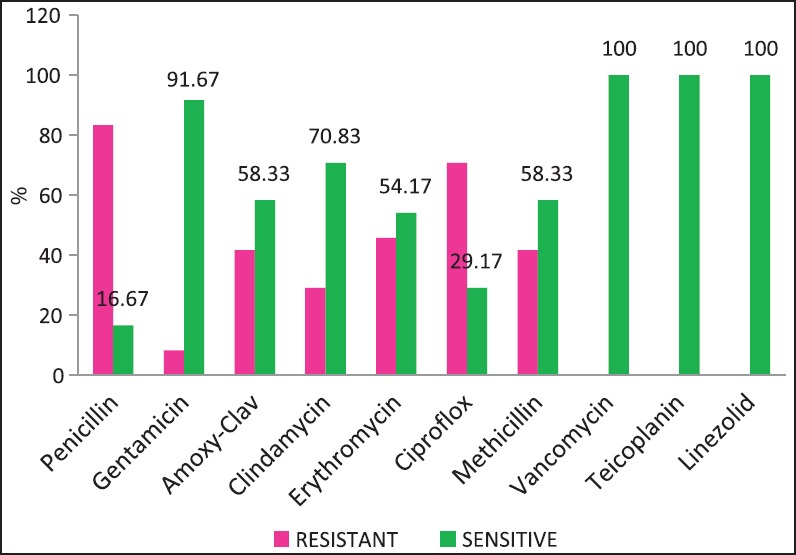

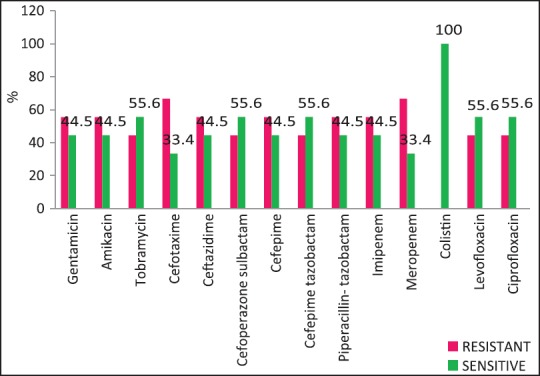

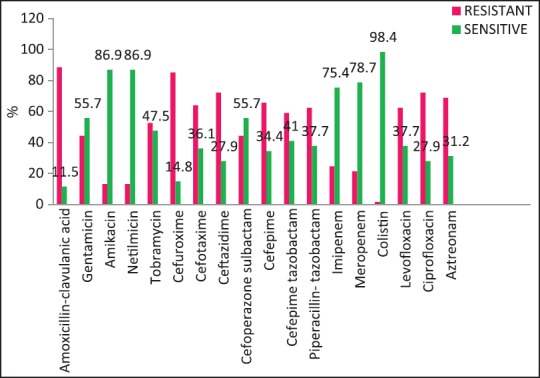

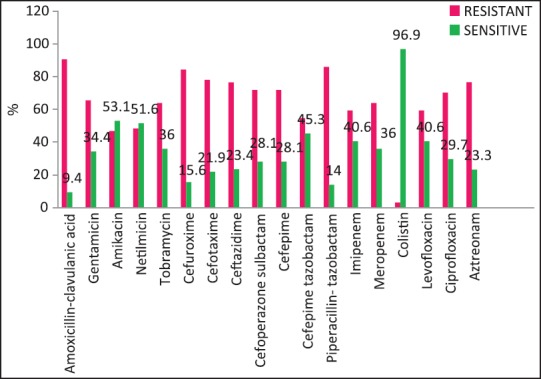

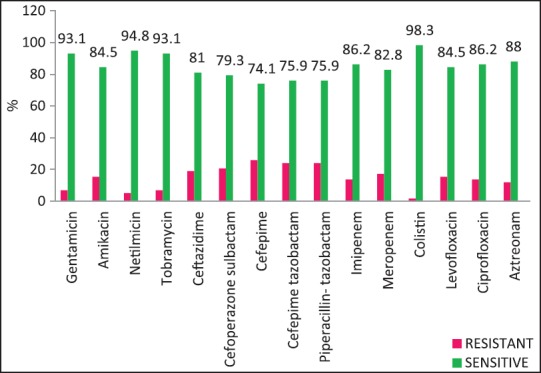

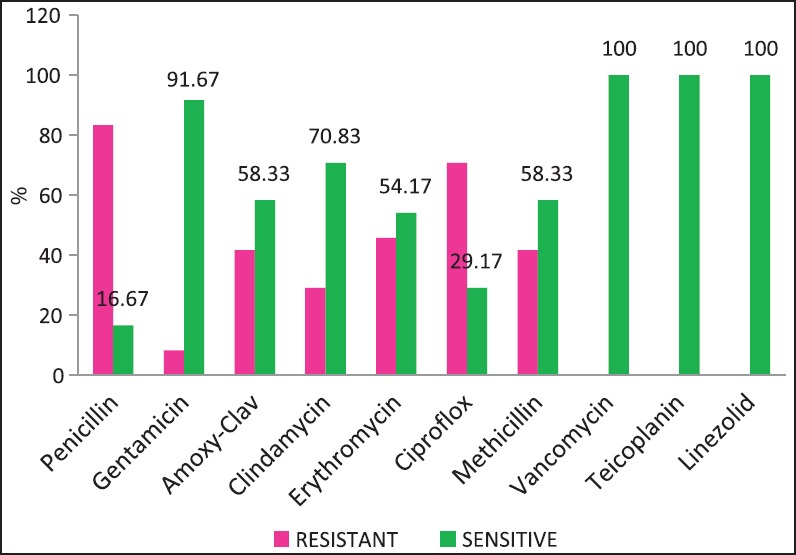

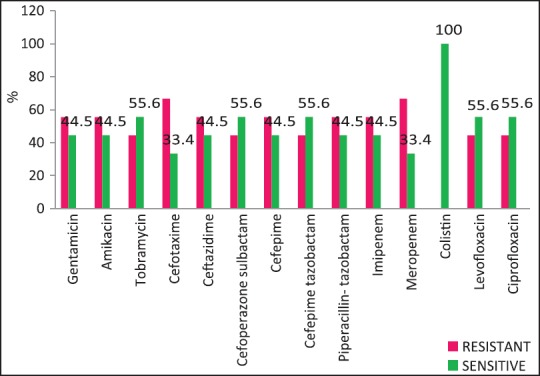

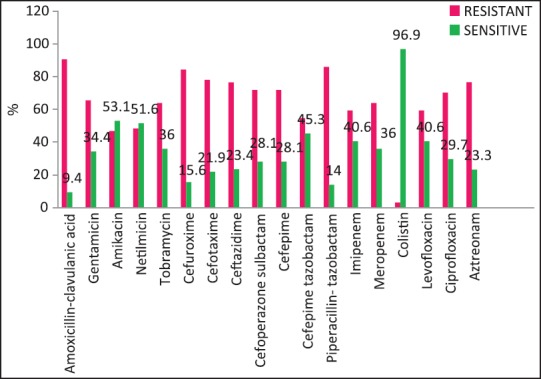

Carbapenem resistance in K. pneumoniae was >50%. Of the S. aureus isolates 41.67% were MRSA (Methicillin Resistant S. aureus). Figures Figures11–5 provide the detailed antibiotic susceptibility patterns for S. aureus, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter spp. respectively.

| Fig. 1 Staphylococcus aureus — susceptibility patterns

| Fig. 5 Acinetobacter spp. susceptibility patterns

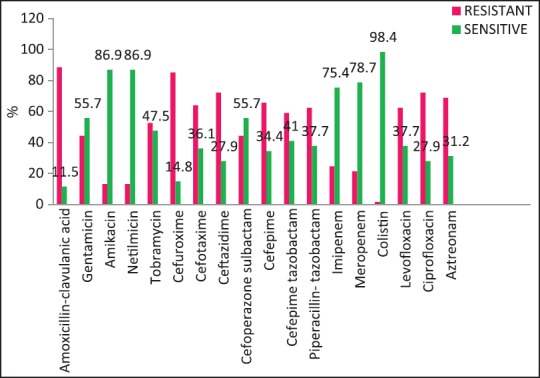

| Fig. 2 Escherichia coli susceptibility patterns

| Fig. 3 Klebsiella pneumoniae susceptibility patterns

DISCUSSION

Pneumonia and bacteremia are common infections seen in cancer patients followed by a urinary tract, skin and soft tissue and gastrointestinal infections.[9] Our study population showed higher numbers of skin and soft tissue infections and lesser numbers of urinary tract infections [Table 1]. The greater numbers of stool cultures in our study reflect also the surveillance cultures that are performed for all our bone marrow transplant patients.

A wide variety of Gram-positive and Gram-negative organisms were isolated from clinical samples in our study [Table 2]. It is striking to note the high rates of resistance of enetrobacteriaceae particularly E. coli and K. pneumoniae to the third generation cephalosporins (cefotaxime/ceftazidime) and also to the β-lactam-β-lactamase inhibitor combinations such as cefoperazone-sulbactam and piperacillin-tazobactam. Similar high rates of resistance of these organisms to the third generation cephalosporins have been noted in a multicentric study across Karnataka[10] and another study from Bhopal.[11] Approximately, half of the E. coli and K. pneumoniae isolates in the above studies were ESBL producers; lesser rates were seen in this study suggesting other methods of cephalosporin resistance also playing an important role in our setting. Fortunately, more than half of E. coli and P. aeruginosa isolates in our study retained clinically useful susceptibility to aminoglycosides (gentamicin, amikacin) and these still have an important role to play in the antibiotic treatment of these organisms in our set up. However >50% of K. pneumoniae and Acinetobacter isolates were resistant to gentamicin.

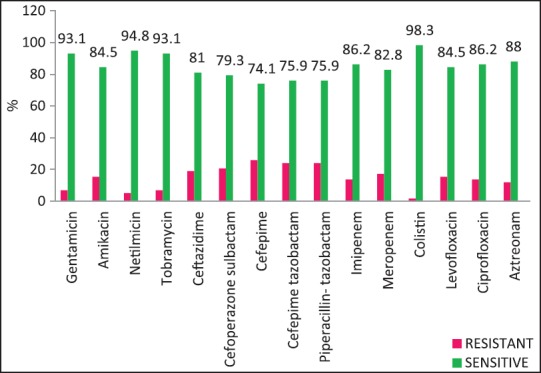

The rate of carbapenems resistant Enterobacteriaceae in the Enterobacteriaceae group of organisms particularly E. coli and K. pneumoniae is a worrying factor. It was much higher than a chinese study that showed only 6.6% carbapenem resistance with less than half of them producing the carbapenemases KPC-2, IMP-4, and NDM-1.[12] One study has identified NDM-1 from different sites in India, mostly among E. coli and K. pneumoniae and these were highly resistant to all antibiotics except tigecycline and colistin.[13] We did not perform molecular studies to identify the carbapenemases in our setting and were, therefore, unable to characterize them. Although the high rate of resistance of P. aeruginosa to piperacillin-tazobactam, amikacin and carbapenems have been described,[14,15] most isolates in our setting were susceptible to primary antipseudomonals, aminoglycosides, and the carbapenems [Figure 4].

| Fig. 4 Pseudomonas aeruginosa — susceptibility patterns

The resistance of Acinetobacter spp. to aminoglycosides and carbapenems was seen to be high in our study [Figure 5]. One study from Odisha, India showed very high rates of resistance of Acinetobacter to ceftazidime (93%), gentamicin (76%) and meropenem (22%).[16] Colistin resistance was seen in rare isolates of Acinetobacter spp. and K. pneumoniae, and is a cause for concern because there are hardly any antibiotic alternatives left for these patients. We have tested select organisms for older drugs such as chloramphenicol, tetracycline, and chloramphenicol in such cases with limited success.

The problem of antibiotic resistance is fortunately not as high among the Gram-positive organisms. High rates of methicillin resistance (Manipal [54%], Puducherry [72.34%],[17,18] and the emergence of vancomycin intermediate strains of S. aureus have been reported from India. We did not encounter any vancomycin resistance among staphylococci, and MRSA rates have been approximate 41.67% [Figure 1].

There is a paucity of studies describing the microbiological profiles and antibiotic susceptibility patterns of organisms isolated from infections in the Indian oncology setting and more reports from similar centers would provide greater insights to this very important emerging issue in this patient population. Important factors leading to the development of resistance include misuse of antibiotics in clinics and hospitals; abundant use of antibiotics in animal farms, aquaculture and poultry; and overuse of anti-infectives and disinfectants.[19] Attempts are being made to formulate antibiotic policies at the national level. The “Chennai declaration” initiative provides directives and recommendations to tackle the menace of antimicrobial resistance at this level.[20] However, it is also important for every healthcare setting to formulate antibiotic policies based on local antibiotic susceptibility patterns to so that arbitrary use of antibiotics is avoided and resistance is kept to a minimum.

CONCLUSION

There is, in general, a high level of antibiotic resistance among Gram-negative bacilli, particularly E. coli, K. pneumoniae and Acinetobacter spp. to the cephalosporins, β-lactam–β-lactam inhibitor combinations and carbapenems group of drugs. Occasional isolates resistant to colistin have also been noted. Resistance among Gram-positive organisms is not as acute, although the MRSA incidence is increasing.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

| Fig. 1 Staphylococcus aureus — susceptibility patterns

| Fig. 5 Acinetobacter spp. susceptibility patterns

| Fig. 2 Escherichia coli susceptibility patterns

| Fig. 3 Klebsiella pneumoniae susceptibility patterns

| Fig. 4 Pseudomonas aeruginosa — susceptibility patterns

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share