Addition of gemcitabine to standard therapy in locally advanced cervical cancer: A randomized comparative study

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2011; 32(03): 133-138

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/0971-5851.92809

Abstract

Background: The concurrent chemoradiotherapy for cervical cancer treatment is well accepted since 1999. This randomized, phase III trial aimed to observe if any improved outcome could be obtained capitalizing on the synergistic activity of gemcitabine, cisplatin, XRT. Materials and Methods: Stage IIB-IIIB, 18-70 years of age, KPS score ≥70, were randomized to control group and study group. Control group received cisplatin 40 mg/m 2 weekly with concurrent XRT, followed by brachytherapy and study group received gemcitabine 125 mg/m 2 weekly top of the same control group treatment. The primary end point was pathological response and toxicities along with patient compliance to treatment, late reactions, DFS and OS. Fifty patients were randomized between two arms. Results: The complete response in study and control arm was 96% and 88% respectively. Toxicities was significantly high in the study group compared to control group [leucopenia (P=0.015), skin reaction (P=0.03) and bleeding (P=0.019)]. Local recurrence rate: 8% in study arm, none in control arm. The distant failure prevailed in control arm (20% vs. 8%). On a median follow up of 21 months in control arm, the DFS was 73% whereas 83% in study arm in 16 months (P=0.69). OS in the study arm was 100% and 84.5% in the control arm (P=0.14). Conclusions: If the toxicity can be managed adequately in the combination chemo radiation group, it may produce an improvement in response. Survival benefit can also be obtained by introducing gemcitabine to cisplatin as radio sensitizer.

Publication History

Article published online:

06 August 2021

© 2011. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Background:

The concurrent chemoradiotherapy for cervical cancer treatment is well accepted since 1999. This randomized, phase III trial aimed to observe if any improved outcome could be obtained capitalizing on the synergistic activity of gemcitabine, cisplatin, XRT.

Materials and Methods:

Stage IIB-IIIB, 18-70 years of age, KPS score ≥70, were randomized to control group and study group. Control group received cisplatin 40 mg/m2 weekly with concurrent XRT, followed by brachytherapy and study group received gemcitabine 125 mg/m2 weekly top of the same control group treatment. The primary end point was pathological response and toxicities along with patient compliance to treatment, late reactions, DFS and OS. Fifty patients were randomized between two arms.

Results:

The complete response in study and control arm was 96% and 88% respectively. Toxicities was significantly high in the study group compared to control group [leucopenia (P=0.015), skin reaction (P=0.03) and bleeding (P=0.019)]. Local recurrence rate: 8% in study arm, none in control arm. The distant failure prevailed in control arm (20% vs. 8%). On a median follow up of 21 months in control arm, the DFS was 73% whereas 83% in study arm in 16 months (P=0.69). OS in the study arm was 100% and 84.5% in the control arm (P=0.14).

Conclusions:

If the toxicity can be managed adequately in the combination chemo radiation group, it may produce an improvement in response. Survival benefit can also be obtained by introducing gemcitabine to cisplatin as radio sensitizer.

INTRODUCTION

In India, carcinoma cervix is the commonest cancer in women. Age-adjusted incidence rates of cervical cancer in India range from 19 to 44/100,000 women. An estimated 371,000 new cases of invasive cervical cancer are diagnosed worldwide each year representing the third most common malignancy in women (after breast and colorectal) and accounts for 190,000 deaths per year.[1,2] It has been estimated that 120,000 women in India newly develop cervical cancer and approximately 80,000 die of this disease every year.[3] Cervical cancer is caused by infection of oncogenic subtypes of human papilloma virus (HPV).[4,5]

Radiotherapy with concurrent cisplatin-based chemotherapy is considered the current treatment standard for bulky FIGO stage IB2-IVA. This combined modality produces an absolute increase in the 5 year survival rate by 12% compared to radiotherapy alone.[6,7] The mechanism that underlies the interaction between drugs and radiation may include inhibition of potentially lethal or sublethal damage repair and an increase in the radiosensitivity of hypoxic cells.[8]

Gemcitabine is a powerful radiosensitizer that has shown encouraging results in a variety of tumor types.[9] So far, it has been shown that gemcitabine is highly synergistic to radiotherapy and cisplatin in cervical cancer cell lines[10] and produces response of more than 40% when used in combination with cisplatin for recurrent and metastases disease.[11] McCormack and Thomas[12] performed a dose finding study of weekly gemcitabine as a single agent concurrent with radiotherapy in cervical cancer stage IB-IV[13] Zarba et al.[14] reported a phase I–II study of cervical cancer patients with stage IIB–IVA disease using cisplatin at 40 mg/m2 plus escalating dose of gemcitabine started at 75 mg/m2 with increment of 25 mg/m2. The result showed that recommended weekly dose of gemcitabine is 125 mg/m2. Data of nine randomized studies on chemoradiotherapy using cisplatin and gemcitabine for cervical cancer have been published, six of which showed benefit from concomitant cytotoxic chemoradiotherapy.[15–20]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

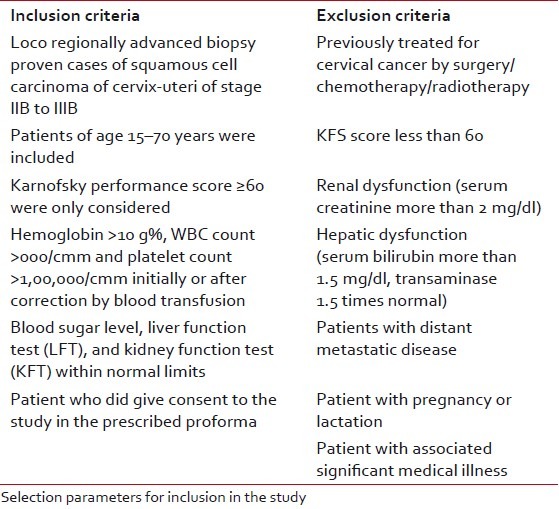

The study was performed at Chittaranjan National Cancer Institute, Kolkata. Patients were enrolled between September 1, 2006 and September 31, 2008. After detailed history, clinical examinations and radiological examinations were carried out for evaluation of primary as well as possible metastases sites and systemic conditions. Cystoscopy was done in suspected urinary bladder involvement cases. Patients were staged according to FIGO criteria. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee beforehand and all the human model study guidelines were maintained according to international criteria. Fifty patients of locally advanced carcinoma cervix patients were enrolled and observed between December 2006 to August 2009. The mean age of the patients in the study group were 51.27 years and that in control group was 51.32 years (P=0.984) [Table 1]. On the basis of above criteria, patients were first selected for the study and each patient was allotted with a computerized randomization number allotted from a trial office. Before participation to the trial, the number was disclosed and matched with the list of arms allotted against that number given to the patient beforehand. This is a simple or unrestricted randomization process.

Table 1

Selection criteria

Treatment protocol

The patients, after signing the informed consent form, were then randomized simply to assign either of the control arms or study arms.

Control arm (Arm A)

Patients received external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) to the whole pelvis to a dose of 50 Gy, delivered in 25# over 5 weeks along with weekly cisplatin at 40 mg/m2. This was followed by three applications of intracavitary brachytherapy within 2–3 weeks of EBRT completion using high dose rate (HDR) Irridium192 at a dose of 7 Gy/# per week at point A.

Study arm (Arm B)

Patients were treated with the same dose of EBRT and brachytherapy with gemcitabine at 125 mg/m2 plus cisplatin at 40 mg/m2 every week. Chemotherapy was given in both the arms 1.5 h before radiation. Pre-chemo and post-chemo hydration (around 1.5 l of infusion fluids), premeditation, and diuretics schedule were maintained stringently. Cisplatin was infused over 1 h and gemcitabine over half-an-hour.

Patients monitoring and evaluation

During treatments patients were monitored once a week to record the patient compliance. Complete blood counts and biochemistry were done weekly. Abnormality was noted according to RTOG criteria. Treatment was withheld according to severity of toxicity and adequate supportive measures were given objectively.

Follow-up

All the patients had their first checkup, one month after the completion of therapy and assessed for response clinically and radiologically including the CT scan abdomen to see the pathological response meticulously. Patients were subsequently followed up at 3-month intervals for at least 1 year as per WHO criteria. At each follow-up, thorough history and clinical examination along with routine blood tests, chest X-rays, USG abdomen, and CT scan were carried out for the assessment of any recurrent or residual disease, pathological response status, and any distant failure. For evaluation of pathological response, Pap smear was mandatory 6 months onwards of completion of treatment.

Late toxicities were graded according to a system applied by Kapp et al.[21] Disease free survival (DFS) was measured from the date of commencement of EBRT to the date of first detection of recurrence of disease, if any. Overall survival was measured from the date of commencement of EBRT till the date of death if obtained or last available follow-up date.

Statistical analysis

The effectiveness of the two treatment arms was correlated with the abovementioned variables by using Fisher's test, Chi-square test, and Student's t-test. A “P” value of ≤0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Survival was estimated by a standard life table actuarial method. DFS curves were computed using the method of Kaplan and Meier. There were two ways used to compute a P value from a contingency table. Fisher's test was the best choice as it always gives the exact P value, while the chi-square test only calculates an approximate P value. The chi-square test was required to calculate for more than two contingency data. With large sample sizes, the Yates correction makes little difference. With small sample sizes, though chi-square is not accurate, the Yates’ continuity correction was used to make the chi-square approximation better. A t-test compares the means of two groups. A t-test was used to calculate the mean follow-up period and mean treatment duration and for comparing continuous variables only.

Institutional ethics committee has always been aware of the experiments undertaken and has approved the study protocol in due time.

RESULTS

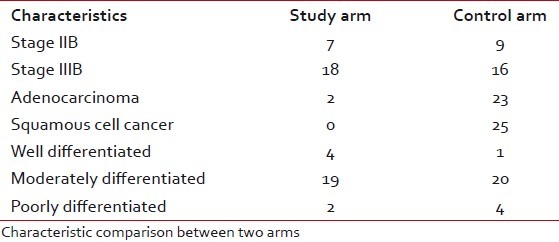

Most of the patients of both the groups were of stage IIIB. Most of the cases in both the arms were diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma. Maximum cases were moderately differentiated carcinoma in both the arms. The pretreatment KPS of the two groups does not show any significant difference. The pretreatment mean hemoglobin level of the patients in the study and control groups was 11.60 g/dl and 11.412 g/dl, respectively [Table 2].

Table 2

Characteristic comparison between two arms

The total duration of therapy was calculated from the first day of starting of EBRT to the day when the last fraction of ICRT was delivered. In the control arm most of the patients completed their treatment within 9 weeks, whereas, in the study arm the treatment time of one-third cases were prolonged up to 11 weeks. Only 10 patients were completed within 10 weeks and eventually produced a statistically significant difference in total duration of therapy (P=0.004). Maximum patients in the study arm had an interruption of 6–10 days, whereas there was only a delay of 1–5 days in the control arm. Leucopenia, skin reaction, and anemia were the most commonly encountered toxicity that caused treatment delay mainly in the study arm.

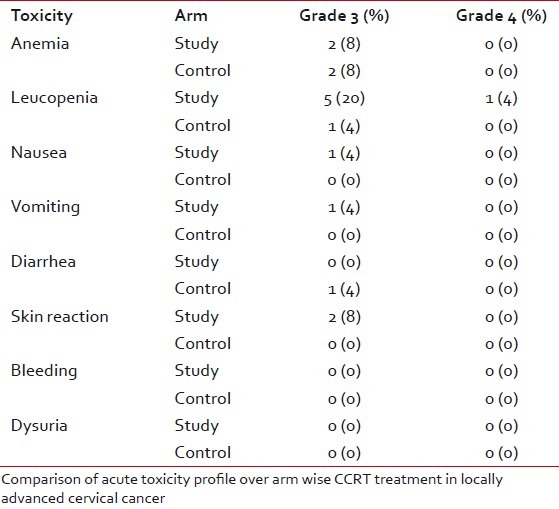

Acute toxicity

The most commonly encountered acute toxicity was anemia. This shows number of grade-3 anemia were the same in both the groups (P=0.426). Compared to anemia, leucopenia was observed in much greater frequency in the study group (P=0.015). Most of the patients in the study and control arm faced mild vomiting throughout the treatment period with no statistical significance (P=0.520). Grade-3 diarrhea was observed only in the control arm (P=0.753). Skin toxicity mainly presented as erythema, dry desquamation, or moist desquamation of skin. Every patient in the study arm showed some of skin reaction. Among them two patients also experienced grade-3 toxicity (P=0.03). Dysuria was the main bladder-related toxicity encountered during treatment (P=0.366) [Table 3].

Table 3

Acute toxicities

Delayed toxicity

Late morbidities of therapy included bladder dysfunction, rectal injury, and skin-soft tissue injury. The overall incidence of late injury was 24% in both the arms (P=1.00).

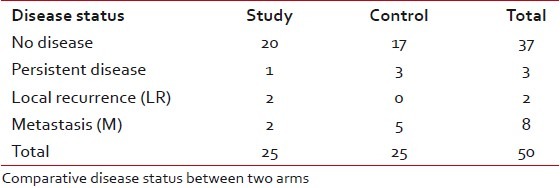

Response

WHO response criteria was followed strictly. Twenty-four (96%) patients in the study arm experienced complete pathological response whereas 22 (88%) patients in the control arm had complete pathological response with no significant statistical difference. There was only one evidence of progressive disease in the control arm (P=0.609) including three patients with partial response. The median follow-up period for the patients completing therapy was 17 months for the study group, and 21 months for the control group, with no statistically significant difference between the two arms. No patient was lost to follow-up. At the end of the follow-up, 20 patients in the study arm and 17 patients in the control arm were observed to be free of disease. There was one case of residual disease in the study arm and three such cases in the control arm. Local recurrence was experienced in two patients in the study arm only; but distant metastases were more in the control arm (5 patients vs. 2 patients) [Table 4].

Table 4

Disease status at the last follow-up

On a median follow-up of 21 months in the control arm, DFS was 73% whereas it was 83% in study arm on a median follow-up of 16 months. Survival benefits in the disease free condition evident from the following Kaplan-Meir curves (P=0.69) [Figure 1].

| Fig. 1 Overall survival

On the same follow-up period, the OS for the control arm was 84.5% and for the study arm it was 100%. Not a single patient died in the study arm and three patients died in the control arm, and the difference in OS within this short span of follow-up were not statistically significant (P=0.14) [Figure 2].

| Fig. 2 Disease-free survival

DISCUSSION

Unfortunately, in developing countries, due to lack of screening and early detection programs, half of the women are diagnosed with locally advanced disease where uncontrolled pelvic disease is the cause of death for most of these women. Thus locoregional control is of paramount importance to improve survival; though this study could not show a significant locoregional control on adding gemcitabine to the standard regime, but the complete pathological response rate was high. In our patient profile, addition of gemcitabine also produced higher toxicity definitely with respect to any statistical survival advantage.

Five randomized phase III control[22–26] trials have shown a survival advantage for cisplatin-based concurrent chemoradiotherapy in women with FIGO stage IB2–IVA cervical cancer. Although the trials did vary in terms of stage of disease, dose of radiation, and schedule of cisplatin and radiation, most of them demonstrated significant survival benefits, decreasing the rate of death by 30–50%.

Gemcitabine has been proved to be a powerful radiosensitizer in cervical cancer cell lines either alone or in combination with cisplatin. Gemcitabine may inhibit repair of the DNA damage caused by radiation leading to increased cell death. It may also induce cell cycle redistribution, causing cells to accumulate in more radiosensitive phase of cell cycle.

At the end of this study, it was observed that complete pathological response was more in the study arm (96%) than in the control arm (88%). The response was better than the similar study of Duenas-Gonzalez et al.[27] where 55% was the complete response rate in the control study arm and 77.5% in the study arm. Umanzor et al.[28] showed 90% complete response with the same protocol as this study. A multicentric, open-level, phase III study (NCT 00191100) with 507 patients is going on with the same study protocol followed by two 21-days adjuvant courses of chemotherapy. This study announced its result updates (30th June, 2009) which showed 87.10% complete response in the study arm and 85.43% in the control arm with no statistical significance (P=0.25). Hence, it is evident that the response rate of the patients in this study is highly comparable or even better in a few cases with the abovementioned studies.

Treatment duration was significantly varied in between two arms in our study (P=0.004). Toxicity was the main cause for treatment hindrance; 28% delay was caused by leucopenia and 16% delay due to skin reaction in the study arm. Anemia happened to be 12% cause of delay in the study arm. Fifteen patients (60%) in the study group faced delayed treatment due to toxicity whereas only 5 patients (20%) in the control arm experienced the same. Duenas-Gonzalez et al. showed only 37% patients who completed treatment in 6 weeks in the gemcitabine-cisplatin arm, when 42% completed in 7 weeks and 19% in 8 weeks period in the same arm. In this study, 40% completed chemotherapy in 6 weeks, 28% in 7 weeks, and 32% in 8 weeks period. The reason may be poor nutritional status, low immunity, and low socioeconomic status of the Indian women with cervical cancer.

Toxicity was observed at the end of each chemotherapy cycle and finally at the end of treatment. Anemia occurred almost equally in both the arms. Duenas-Gonzalez et al. showed that hemoglobin-related toxicity was almost comparable with the reference study. Two out of 23 patients in the gemcitabine-cisplatin arm (8.69%) faced grade-3 anemia in a study by Umanzor et al.

Leucopenia occurred significantly in the study group in this study. Duenas-Gonzalez et al. found that incidence of leucopenia nearly matched with our study. The difference was statistically significant. Umanzor et al. found only less than 5% grade-2 leucopenia. Low study power, better immunity, and good physical status of the patients might be the cause for the low rate of neutropenic toxicity in the reference studies.

Nausea between the two arms was not statistically significant (P=0.554). It was evident in this study that nausea did not cause much treatment interruption and it was quite manageable. Other reference studies such as Duenas-Gonzalez et al. and Umanzor et al. also found the same result. Vomiting was encountered in this study not in a very discriminating number between the two arms.

Lower gastrointestinal toxicity in the form of diarrhea occurred in both the arms almost equally (P=0.753). Duenas-Gonzalez et al. had much more number of lower GI toxicity; 5% and 7% grade-3 diarrhea came out in the control and study arms, respectively. Bleeding during treatment was significantly high in the study arm as more bulky tumors were randomized into the study arm.

This skin reactions significantly prolonged the treatment period in 16% of patients in the study arm (P=0.03). Skin reaction was significantly low in the Duenas-Gonzalez study. The use of telecobalt machine and more thick interfield distance (in around 30% of patients) might be the cause of increased toxicity in this study.

Dysuria usually started fourth to fifth week onwards in both the arms. There was no significant difference between the arms in this respect. Other reference studies also supported the fact.

Notification of late toxicities in this study had not been optimum because of a short follow-up duration and so no proper comparison could be done with other similar studies in this respect.

On a median follow-up duration of 21 months for the control arm, 73% patients did show disease-free status whereas on 16 months of median follow-up in the study arm, 83% patients remained disease-free.

Again on a median follow-up duration of 21 months in the control arm the overall survival (OS) was 84.5% and on median follow-up of 16 months, in the study arm it was recorded to be 100%. Therefore, there was a distinct superiority found numerically in the combined chemotherapy group with respect to treatment response over the platinum-only group. McCormack and Thomas et al. studied 10 previously untreated locally advanced cervical cancer with teletherapy, intracavitary brachytherapy, and weekly escalating dose of gemcitabine for 6 weeks and on a median follow-up of 29 months they found all but one patient is disease free. Duenas-Gonzalez et al. recorded at the end of their study that on a median follow up of 20 months, 2 (5%) out of 40 patients in the control arm had pelvic and systemic progressive diseases. Two had pelvic recurrence and one had systemic relapse alone. Only one patient developed a distant failure in brain in the combination group and the remaining patients were disease free at the last follow-up. Therefore, comparatively their study arm result was marginally better than this study.

Thus, we can infer that this study, though came out with the comparable pathological response rate to the international studies, it showed the loco regional relapse rate marginally high in the study group. The reason behind slightly high loco regional relapse might be protracted treatment due to radiation reaction or withholding of chemotherapy due to their toxicity difficult to manage.

Occurrence of toxicities were significantly high in the study group compared to the control group in the case of leucopenia (P=0.015), skin reaction (P=0.03), and bleeding (P=0.019) but other toxicity parameters were almost the same in both the groups. Thus, the abovementioned toxicities were to be taken care of in the study arm meticulously to get the advantage of higher response rate.

CONCLUSION

If the toxicity can be managed adequately in the combination chemoradiation group and the treatment duration is restricted within the stipulated period of time, it may produce a significant response rate. Survival benefit can also be obtained by introducing gemcitabine to cisplatin as a radiosensitizer.

Considering the better result, however small, achieved in the study arm with respect to tumor control and patient survival, further studies are warranted with a bigger patient sample and longer duration of follow-up, so that the actual effectiveness of the current regimen could be declared conclusively.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

| Fig. 1 Overall survival

| Fig. 2 Disease-free survival

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share