A Report of an Unusual Case of Pediatric Eosinophilia Associated with Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor-Beta Rearrangement

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 · Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2020; 41(05): 752-755

DOI: DOI: 10.4103/ijmpo.ijmpo_259_20

Abstract

Eosinophilia is a common finding in the pediatric age group. While the majority of mild eosinophilia cases are benign and due to reactive causes, persistent hypereosinophilia is uncommon and requires prompt clinical evaluation because of the potential risk of end-organ damage associated with it. Given the broad differential diagnoses of eosinophilia, it is essential to have a systematic approach to the evaluation of unexplained eosinophilia in children. Here, we discuss the case of a 2-year-old child who presented with very high eosinophil counts. A systematic workup of the case helped us in arriving at a rare diagnosis of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta (PDGFRB)-rearranged clonal eosinophilia. Identification of such an entity is important as it has therapeutic implications, and early recognition helps in preventing associated end-organ damage by instituting appropriate therapy. Such cases of eosinophilia associated with platelet-derived growth factor receptor-alpha and PDGFRB rearrangement respond dramatically to imatinib.

Keywords

Children - eosinophilia - hypereosinophilia - imatinib - platelet-derived growth factor receptor-betaPublication History

Received: 26 May 2020

Accepted: 20 August 2020

Article published online:

17 May 2021

© 2020. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

Abstract

Eosinophilia is a common finding in the pediatric age group. While the majority of mild eosinophilia cases are benign and due to reactive causes, persistent hypereosinophilia is uncommon and requires prompt clinical evaluation because of the potential risk of end-organ damage associated with it. Given the broad differential diagnoses of eosinophilia, it is essential to have a systematic approach to the evaluation of unexplained eosinophilia in children. Here, we discuss the case of a 2-year-old child who presented with very high eosinophil counts. A systematic workup of the case helped us in arriving at a rare diagnosis of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta (PDGFRB)-rearranged clonal eosinophilia. Identification of such an entity is important as it has therapeutic implications, and early recognition helps in preventing associated end-organ damage by instituting appropriate therapy. Such cases of eosinophilia associated with platelet-derived growth factor receptor-alpha and PDGFRB rearrangement respond dramatically to imatinib.

Keywords

Children - eosinophilia - hypereosinophilia - imatinib - platelet-derived growth factor receptor-betaIntroduction

Peripheral blood eosinophilia is a common finding even in asymptomatic children. Eosinophils are terminally differentiated granulocytes representing < 5% of the circulating leukocyte population. For children aged above 2 years, eosinophilia is classified into mild (absolute eosinophil count [AEC] 500–1500/mm3), moderate (AEC 1500–5000/mm3), and severe (AEC >5000/mm3).[1] Hypereosinophilia, defined as blood AEC more than 1500/mm3, is uncommon and requires urgent clinical evaluation to determine etiology and to prevent possible end-organ damage. Primary (clonal) eosinophilia should be considered, especially in the setting of persistent hypereosinophilia or eosinophilia associated with end-organ damage. We discuss the case of a 2-year-old child who presented with very high eosinophil counts.

Case Report

A 2-year-old male child, developmentally normal and appropriately immunized for age, presented to us with a 5-month history of intermittent fever and recurrent episodes of cough associated with fast breathing. He also had nonprogressive abdominal distension and two episodes of oral thrush about 4 months before presentation. There was no history of skin ulcers, pruritus, irritability, weight loss, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Family history was negative for atopy or asthma, and other sibling was healthy. There was no history of regular drug intake before presentation. During evaluation, the child was found to have elevated total leukocyte counts (38,000/mm3) with AEC of 15,200/mm3, for which he was treated with multiple antihelminthics (albendazole and diethylcarbamazine) and a short 5-day course of oral steroids. Since the symptoms did not resolve, he was referred us. On examination, the child had mild pallor and no clubbing, lymphadenopathy, skin rashes, skin nodules, or oral thrush. His vitals were normal for age, and he was not tachypneic or hypoxic. His liver was palpable 6 cm and spleen 2 cm below costal margin. Cardiovascular and nervous system examination was within normal limits.

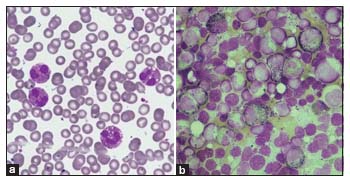

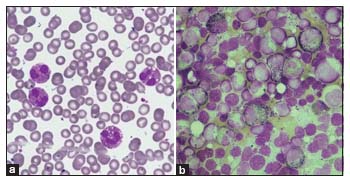

Baseline investigations confirmed hypereosinophilia with the peripheral smear showing increased eosinophils with atypical nuclear segmentation and cytoplasmic vacuolation and no immature myeloid precursors [Figure 1a]. The differentials considered were parasitic infections (including visceral larva migrans and tropical pulmonary eosinophilia), asthma with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and primary immunodeficiencies such as hyper-IgE, malignancies, and clonal or idiopathic hypereosinophilia. Eosinophilia-related organ dysfunction was ruled out by detailed clinical examination, ECHO, and troponin-I. As there were infiltrates and minimal pleural effusion on chest X-ray with abnormal contrast-enhanced computed tomography findings, bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage were done and were normal. Parasitic infections as a cause of eosinophilia were ruled out by stool microscopic examinations for ova/eggs, peripheral smear and serology for filariasis. Renal/liver functions and serum Vitamin B12 were normal. Although serum IgE levels were elevated, the clinical phenotype was not consistent with hyper-IgE syndrome. Primary immunodeficiency panel was normal. Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy showed significant eosinophilia (22%) and increase in eosinophilic precursors with no increase in blasts, mast cells, or marrow fibrosis [Figure 1b]. Immunophenotyping was normal by flow cytometry.

| Figure 1: (a) Peripheral smear showing increase in mature eosinophils with cytoplasmic vacuolation and hypogranular cytoplasm. No atypical cells seen (b) Bone marrow aspirate showing hypercellular marrow with increase in eosinophils and eosinophilic precursors. No atypical cell or increase in blasts

After ruling out secondary causes, clonal eosinophilia was suspected. Peripheral blood was sent for FIP1 L1- platelet-derived growth factor receptor-alpha(PDGFRA) gene rearrangement by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and was negative. A repeat bone marrow aspiration was done which was positive for ETV6/ platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta(PDGFRB) rearrangement by RT-PCR. Fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 (FGFR1) gene rearrangement was negative. Hence, a final diagnosis of myeloid neoplasm with eosinophilia and ETV6-PDGFRB rearrangement (t[5;12]) was arrived at and the patient was started on imatinib therapy.

Discussion

Hypereosinophilia is defined as the peripheral blood AEC ≥1500 cells/mm3 obtained on two separate occasions at least 1 month apart or marked tissue eosinophilia.[1] The term hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) describes hypereosinophilia with the evidence of end-organ damage directly attributable to tissue eosinophilia.[2] Eosinophils can infiltrate various tissues and release granules, leading to wide spread organ dysfunction. In the lungs, it can cause airway hyperresponsiveness, eosinophilic pneumonitis, fibrosis, and pleural effusions. Most dreaded of eosinophilia-related organ dysfunction is cardiac where it can lead to endocardial necrosis and fibrosis, valvular dysfunction, and thrombosis. Neurological manifestations include peripheral neuropathy, mononeuritis multiplex, thromboembolism, and central nervous system vasculitis.[3] Prompt recognition of the end-organ dysfunction and treatment with corticosteroids forms the cornerstone for the management of HES. The causes of hypereosinophilia can be divided into primary (clonal/neoplastic), secondary (reactive), hereditary (familial), and hypereosinophilia of undetermined significance. The term “idiopathic hypereosinophilia” term should be reserved for hypereosinophilia after ruling out secondary and clonal causes.[4] The most common secondary cause identified for hypereosinophilia was parasitic infection, with an incidence ranging from 10% to 35% in various pediatric and adult series.[5] Primary or clonal eosinophilia includes clonal eosinophilia with recurring genetic aberrations (PDGFRA, PDGFRB, FGFR1, or Janus kinase-2 [JAK-2] mutation) and chronic eosinophilia, not otherwise specified.

The most common causes for clonal eosinophilia are the ones associated with FIP1 L1-PDGFRA rearrangements, with a reported incidence ranging from 3% to 17%.[6] FIP1 L1-PDGFRA results from a submicroscopic interstitial deletion on chromosome 4 and is cytogenetically occult. The deleted segment contains the CHIC2 gene, and hence, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for the CHIC2 deletion and/or RT-PCR is employed to detect the fusion.[7] The fusion can be detected in the peripheral blood, bone marrow smears, or involved tissues. PDGFRB rearrangement, the genetic aberration detected in the index child, has more than 30 additional fusion partner genes involved in translocation. The most common translocation is t(5;12)(q33;p13)/ETV6-PDGFRB.[4],[8] Clinically, it presents as a chronic myelomonocytic leukemia with eosinophilia. The t(5;12)(q33;p13) juxtaposes the ETV6 gene at 12p13 with the PDGFRB gene at 5q33. The PDGFRB gene encodes a Class III receptor tyrosine kinase, and several genes encoding eosinophilopoietic cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-3, IL-5, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor reside in the 5q31;33 region.[4] The t(5;12) results in the constitutive activation of PDGFRB and downstream activation of cell signaling pathways regulating hematopoiesis such as STAT-5 and nuclear factor KB, which promote cell growth and proliferation. The fusion oncogene is believed to induce eosinophilia by increasing the expression of IL-5 receptor-alpha chain and eosinophil peroxidase. Conventional cytogenetics can be used to identify the involvement of PDGFRB on chromosome 5q33, as in almost all instances such cases are associated with translocations, unlike with PDGFRA. The presence of PDGFRB rearrangements can also be detected using break-apart FISH, but this approach fails to identify the gene partner. RT-PCR methods using specific primer sets also can be employed if the partner of PDGFRB is known.[8]

PDGFRB-rearranged myeloid neoplasms with eosinophilia are more common in adults but are extremely rare in children; the youngest case was diagnosed at 5 months of age.[9] To the best of our knowledge, only seven such cases have been reported in the pediatric literature previously [Table 1].[10],[11],[12],[13],[14] Out of these, three patients had t (5;12)/ETV6-PDGFRB translocation, three had t(1;5)(q23;q33) translocation, and in the remaining patient, the PDGFRB fusion partner was unknown. Both PDGFRA and PDGFRB rearrangements result in clonal eosinophilia, which is responsive to therapy with imatinib and has excellent long-term outcomes with a very low risk of blast transformation. In a retrospective cohort of 26 patients (adult and pediatric) diagnosed with PDGFRB-rearranged myeloid neoplasms with eosinophilia treated with imatinib, the 10-year overall survival rate was 90% after a median follow-up of 10.2 years.[15] FGFR1-rearranged and JAK-2-mutated clonal eosinophilias show poor response to imatinib, have a higher risk of blast transformation, and guarded prognoses. They may show some response to ponatinib and ruxolitinib, respectively, and commonly require hematopoietic stem cell transplant.[16]

Table 1 Baseline, hematological, and cytogenetic data of pediatric PDGFRB rearranged cases

Conclusion

Eosinophilia requires an algorithmic approach for identification of etiology, and all cases are not synonymous with parasitic infections or allergy. End-organ dysfunction has to be ruled out in persistent eosinophilia, and if present, corticosteroids have to be initiated urgently. Although PDGFRB rearranged clonal eosinophilia is a well-known entity, it is rare in pediatric age group and even rarer in a 2-year-old child. PDGFRB-rearranged clonal eosinophilia responds well to tyrosine kinase inhibitor, imatinib. The index case showed excellent response to imatinib at a dose of 360 mg/m2/day with normal eosinophil counts after a month of therapy. He is currently into 10 months of follow-up and is asymptomatic.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Valent P, Klion AD, Horny HP, Roufosse F, Gotlib J, Weller PF. et al. Contemporary consensus proposal on criteria and classification of eosinophilic disorders and related syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 130: 607-12, e609

- Klion AD. How I treat hypereosinophilic syndromes. Blood 2015; 126: 1069-77

- Akuthota P, Weller PF. Spectrum of eosinophilic end-organ manifestation. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2015; 35: 403-11

- Reiter A, Gotlib J. Myeloid neoplasms with eosinophilia. Blood 2017; 129: 6

- Williams KW, Ware J, Abiodun A, Holland-Thomas NC, Khoury P, Klion AD. Hypereosinophilia in children and adults: A retrospective comparison. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2016; 4: 941-70

- Pardanani A, Brockman SR, Paternoster SF, Flynn HC, Ketterling RP, Lasho TL. et al. FIP1 L1-PDGFRA fusion: Prevalence and clinicopathologic correlates in 89 consecutive patients with moderate to severe eosinophilia. Blood 2004; 104: 3038-45

- Pardanani A, Ketterling RP, Brockman SR, Flynn HC, Paternoster SF, Shearer BM. et al. CHIC2 deletion, a surrogate for FIP1 L1-PDGFRA fusion, occurs in systemic mastocytosis associated with eosinophilia and predicts response to imatinib mesylate therapy. Blood Blood 2003; 102: 3093-6

- Vega F, Medeiros LJ, Bueso-Ramos CE, Arboleda P, Miranda RN. Hematolymphoid neoplasms associated with rearrangements of PDGFRA, PDGFRB, and FGFR1. Am J Clin Pathol 2015; 144: 377-92

- Darbyshire PJ, Shortland D, Swansbury GJ, Sadler J, Lawler SD, Chessells JM. A myeloproliferative disease in two infants associated with eosinophilia and chromosome t(1;5) translocation. Br J Haematol 1987; 66: 483-6

- Pellier I, Le Moine PJ, Rialland X, François S, Baranger L, Blanchet O. et al. Myelodysplastic syndrome with t(5;12)(q31;p12-p13) and eosinophilia: A pediatric case with review of literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 1996; 18: 285-8

- Jani K, Kempski HM, Reeves BR. A case of myelodysplasia with eosinophilia having a translocation t(5;12) (q31;q13) restricted to myeloid cells but not involving eosinophils. Br J Haematol 1994; 87: 57-60

- Wilkinson K, Velloso ER, Lopes LF, Lee C, Aster JC, Shipp MA. et al. Cloning of the t(1;5)(q23;q33) in a myeloproliferative disorder associated with eosinophilia: Involvement of PDGFRB and response to imatinib. Blood 2003; 102: 4187-90

- Wittman B, Horan J, Baxter J, Goldberg J, Felgar R, Baylor E. A 2-year-old with atypical CML with a t(5;12)(q33;p13) treated successfully with imatinib mesylate. Leuk Res 2004; 28: S65-9 et al. suppl 1

- Bastie JN, Garcia I, Terré C, Cross NC, Mahon FX, Castaigne S. Lack of response to imatinib mesylate in a patient with accelerated phase myeloproliferative disorder with rearrangement of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta-gene. Haematologica 2004; 89: 1263-4

- Cheah CY, Burbury K, Apperley JF, Huguet F, Pitini V, Gardembas M. et al. Patients with myeloid malignancies bearing PDGFRB fusion genes achieve durable long-term remissions with imatinib. Blood 2014; 123: 3574-7

- Schwaab J, Knut M, Haferlach C, Metzgeroth G, Horny HP, Chase A. et al. Limited duration of complete remission on ruxolitinib in myeloid neoplasms with PCM1-JAK2 and BCR-JAK2 fusion genes. Ann Hematol 2015; 94: 233-8

Address for correspondence

Publication History

Received: 26 May 2020

Accepted: 20 August 2020

Article published online:

17 May 2021

© 2020. Indian Society of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

A-12, 2nd Floor, Sector 2, Noida-201301 UP, India

| Figure 1: (a) Peripheral smear showing increase in mature eosinophils with cytoplasmic vacuolation and hypogranular cytoplasm. No atypical cells seen (b) Bone marrow aspirate showing hypercellular marrow with increase in eosinophils and eosinophilic precursors. No atypical cell or increase in blasts

References

- Valent P, Klion AD, Horny HP, Roufosse F, Gotlib J, Weller PF. et al. Contemporary consensus proposal on criteria and classification of eosinophilic disorders and related syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 130: 607-12, e609

- Klion AD. How I treat hypereosinophilic syndromes. Blood 2015; 126: 1069-77

- Akuthota P, Weller PF. Spectrum of eosinophilic end-organ manifestation. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2015; 35: 403-11

- Reiter A, Gotlib J. Myeloid neoplasms with eosinophilia. Blood 2017; 129: 6

- Williams KW, Ware J, Abiodun A, Holland-Thomas NC, Khoury P, Klion AD. Hypereosinophilia in children and adults: A retrospective comparison. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2016; 4: 941-70

- Pardanani A, Brockman SR, Paternoster SF, Flynn HC, Ketterling RP, Lasho TL. et al. FIP1 L1-PDGFRA fusion: Prevalence and clinicopathologic correlates in 89 consecutive patients with moderate to severe eosinophilia. Blood 2004; 104: 3038-45

- Pardanani A, Ketterling RP, Brockman SR, Flynn HC, Paternoster SF, Shearer BM. et al. CHIC2 deletion, a surrogate for FIP1 L1-PDGFRA fusion, occurs in systemic mastocytosis associated with eosinophilia and predicts response to imatinib mesylate therapy. Blood Blood 2003; 102: 3093-6

- Vega F, Medeiros LJ, Bueso-Ramos CE, Arboleda P, Miranda RN. Hematolymphoid neoplasms associated with rearrangements of PDGFRA, PDGFRB, and FGFR1. Am J Clin Pathol 2015; 144: 377-92

- Darbyshire PJ, Shortland D, Swansbury GJ, Sadler J, Lawler SD, Chessells JM. A myeloproliferative disease in two infants associated with eosinophilia and chromosome t(1;5) translocation. Br J Haematol 1987; 66: 483-6

- Pellier I, Le Moine PJ, Rialland X, François S, Baranger L, Blanchet O. et al. Myelodysplastic syndrome with t(5;12)(q31;p12-p13) and eosinophilia: A pediatric case with review of literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 1996; 18: 285-8

- Jani K, Kempski HM, Reeves BR. A case of myelodysplasia with eosinophilia having a translocation t(5;12) (q31;q13) restricted to myeloid cells but not involving eosinophils. Br J Haematol 1994; 87: 57-60

- Wilkinson K, Velloso ER, Lopes LF, Lee C, Aster JC, Shipp MA. et al. Cloning of the t(1;5)(q23;q33) in a myeloproliferative disorder associated with eosinophilia: Involvement of PDGFRB and response to imatinib. Blood 2003; 102: 4187-90

- Wittman B, Horan J, Baxter J, Goldberg J, Felgar R, Baylor E. A 2-year-old with atypical CML with a t(5;12)(q33;p13) treated successfully with imatinib mesylate. Leuk Res 2004; 28: S65-9 et al. suppl 1

- Bastie JN, Garcia I, Terré C, Cross NC, Mahon FX, Castaigne S. Lack of response to imatinib mesylate in a patient with accelerated phase myeloproliferative disorder with rearrangement of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta-gene. Haematologica 2004; 89: 1263-4

- Cheah CY, Burbury K, Apperley JF, Huguet F, Pitini V, Gardembas M. et al. Patients with myeloid malignancies bearing PDGFRB fusion genes achieve durable long-term remissions with imatinib. Blood 2014; 123: 3574-7

- Schwaab J, Knut M, Haferlach C, Metzgeroth G, Horny HP, Chase A. et al. Limited duration of complete remission on ruxolitinib in myeloid neoplasms with PCM1-JAK2 and BCR-JAK2 fusion genes. Ann Hematol 2015; 94: 233-8

PDF

PDF  Views

Views  Share

Share